Siunik Moradian is coming to grips with a massive pay cut.

The 27-year-old Los Angeles corporate attorney walked off the job in April after his firm, Simpson Thacher & Bartlett, struck a deal with President Donald Trump. He wants to work as a public defender, where he can expect to make about one third of the $315,000-plus he was on track to earn as a third-year associate at the firm.

“It is going to be impossible both in the short and long term to come close to the wealth I could have accumulated for myself and my family had I remained in Big Law,” said Moradian. “I was fortunate enough to be able to just barely pay off my student loans before leaving.”

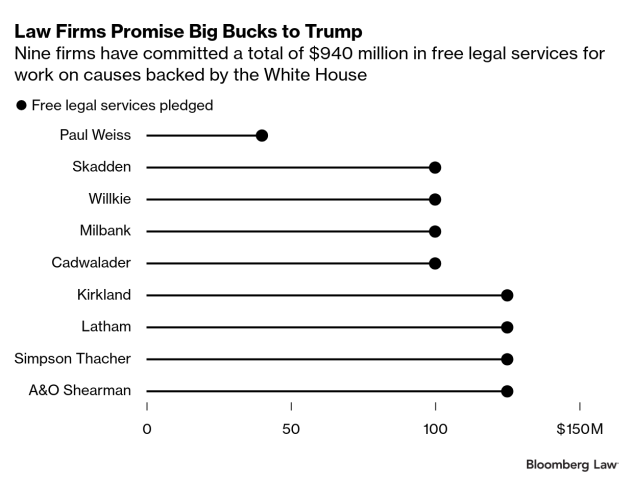

Moradian is among a small group of junior lawyers who loudly quit after their firms made deals with Trump, pledging nearly $1 billion in free legal services on shared causes to avoid punitive executive orders like those aimed at their competitors. At least 12 associates took their resignation notices public, accusing their firms of “capitulating” or “bending the knee” to Trump in LinkedIn posts, emails that were quickly leaked, and interviews with media outlets.

Some of the attorneys are resurfacing months later in jobs outside of Big Law, from running for Congress to working at a small firm taking on the Trump administration. But a majority of the lawyers who left in protest are between jobs, according to interviews with a number of them and LinkedIn profiles for the others.

Most who spoke with Bloomberg Law said they don’t anticipate being welcomed back to any of the country’s largest law firms—nor do they want to return.

“It’s risky to loudly quit on this issue,” especially without another job lined up, said Jolie Steppe, an associate recruiter at Greene-Levin-Snyder Legal Search Group. “The candidate pool is so deep that the majority of candidates do not have a gap, and law firms are very conservative in their hiring.”

Those that have landed new roles say they found work that allows them to be more explicit about their personal beliefs. Those who are still looking say they want jobs that better align with their values.

No Regrets

Rachel Cohen was among the earliest to jump ship over the Trump pacts, leaving Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom in March. She organized a group of more than 1,500 associates who anonymously signed an open letter condemning the White House’s crackdown on Big Law.

“I don’t think you can stage a four-month-long organizing effort against the powers that be and go back and work in an industry that prioritizes deference to the powers that be over anything else,” she said.

Cohen said she didn’t expect anyone to join her in speaking publicly against their firms because of the financial consequences of leaving their jobs.

She is now working at the small firm launched by Abbe Lowell, the prominent litigator who left Winston & Strawn to focus on taking cases against the Trump administration.

Associate positions at top firms are prestigious and lucrative, with seniority-based pay scales that range from $225,000 to $435,000, before bonuses. Average equity partner pay at the firms that made deals with Trump ranged from $2.7 million to $9.2 million last year, according to data from The American Lawyer.

“Clients don’t want to be involved in a controversy,” said Matt Schwartz, an associate recruiter with search firm Garrison. “A client could be pro-Trump or a client might not like someone who brings that kind of attention to themselves.”

Two former Big Law associates said they have no regrets about speaking out against their firms.

A former Kirkland & Ellis associate, one of a handful who quit over the deals, is looking for jobs in state government and nonprofit organizations. The other wants to return to a law firm, but is focusing on those that publicly supported Perkins Coie and others hit with executive orders.

They asked for anonymity to speak freely about their career plans without derailing them.

Moradian announced his departure from Simpson Thacher the same day Trump unveiled his agreement with the firm, in which it agreed to provide $125 million in free legal services.

“I will not sleepwalk toward authoritarianism,” he said in an April 11 email that became public within hours.

Cohen was one of at least three associates who bolted from Skadden over the firm’s White House deal. Brenna Trout Frey, a Washington-based products liability lawyer, also left the firm for Lowell’s boutique. Frey is working in a counsel role, while Cohen is handling the firm’s media relations on a part-time basis.

The vocal departures over the industry’s response to Trump have mostly been contained to the associate ranks. A handful of Willkie Farr & Gallagher associates slammed the firm for its agreement with Trump, but not until after they followed a group of seven partners to Cooley LLP. The Silicon Valley firm’s lawyers are representing Jenner & Block in challenging Trump’s executive order against it.

More lawyers are leaving over the pacts, but most are keeping their reasons private, according to Schwartz. Partners, who earn more and control client relationships, have more to lose than associates by speaking out, he said. But associates often have significant debt hanging over their heads.

About 85% of law students take out loans to pay for their education, according to a 2024 American Bar Association survey. Those students graduate with a median of $137,500 in debt.

Schwartz said law firms tend to view vocal lawyers, especially those who sound off on decisions made by their managers, as a liability.

“It makes their candidacy difficult, but not impossible,” he said. “Other firms may welcome them, especially boutiques who are really taking a strong stance against the administration.”

Bridges Burned?

Ryan Powers did not quit, but the former Davis Polk & Wardwell associate sounded off on hot-button political issues before being shown the door.

Powers was fired in June after he criticized the Trump administration and its allies in opinion pieces published in various newspapers. He said the firm told him he broke firm policy by failing to gain its approval to publish the op-eds.

Powers said he initially reconciled himself to never working in Big Law again.

“I had a mentor of mine tell me lovingly that I should expect to be unemployed for the next three years and to just be prepared for that and make sure that I had the resources if that happened,” Powers said in an interview.

Podcast: Skadden Is Heading Down a ‘Craven Path,’ Associate Says

Powers says he will draw on savings from his Davis Polk tenure while looking for a new position. He thinks his best shot is with “mission-driven” firms, like those that signed onto a brief supporting Trump-targeted firm Perkins Coie’s lawsuit against the administration. Only eight of the 100 biggest law firms in the US signed onto the brief, including those that already were in litigation with Trump.

Taylor Wettach, another former Simpson Thacher associate, doesn’t expect to get rehired anytime soon at Big Law firms. He’s squarely focused on a long-shot run for Congress in Iowa.

Wettach, who left the firm in May, has made Simpson Thacher’s deal with Trump a talking point.

“The rule of law in our country is priority number one,” he said. “My experience standing up for what I believe in makes me better prepared to advocate for all Iowans.”

Moradian thinks the door to Big Law isn’t closed for him. He said partners at other firms he’s worked with and recruiters have reached out about potential opportunities.

He decided instead to go into public defense “given all that is happening to the degradation of fundamental human rights in the US, particularly under this authoritarian administration.”

He’s trying not to mourn his former paycheck.

“I’m hesitant to say ‘woe is me’ when even my salary as a public defender will be above the median in the US,” Moradian said.

To contact the reporters on this story:

To contact the editors responsible for this story:

Learn more about Bloomberg Law or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

Bloomberg Law provides trusted coverage of current events enhanced with legal analysis.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.