Since 1962, domestic partnerships have been treated as separate entities when determining an investor’s Subpart F inclusion. This simple fact shaped the way an entire industry structured foreign investment for over half a century.

Following the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) and the release of several proposed regulations, this foundational principal began to show cracks, but appeared resilient to change. However, in mid-2019, the IRS re-wrote history with the release of final (T.D. 9866) and proposed (REG-101828-19) regulations addressing the treatment of partners in domestic partnerships. These regulations provide new rules that look to treat partnerships as an aggregate of their partners, rather than as entities, when determining global intangible low-taxed income (GILTI) or Subpart F income inclusions (the “deemed inclusions”).

BACKGROUND

Generally, a shareholder of a corporation is not taxed on income earned by the corporation until the income is distributed to its shareholders. However, the Subpart F regime allows the IRS to tax certain income earned by a controlled foreign corporation (CFC), regardless of whether the CFC has distributed income to its shareholders during the current tax year. In December 2017, the TCJA also added Section 951A which requires a U.S. shareholder (i.e., a U.S. person that holds directly, indirectly or constructively 10% or more in a foreign corporation) of any CFC to include in gross income the shareholder’s GILTI inclusion.

Prior to the enactment of Subpart F, many U.S. taxpayers achieved deferral of U.S. tax on portable income, such as dividends and interest, through the use of foreign corporations, often located in low- or no-tax jurisdictions. Congress determined that this type of deferral was inappropriate and enacted Subpart F to require immediate taxation of certain mobile income. The enactment of TCJA ended deferral for most corporations and significantly limited it for individuals, but provided an exemption from taxation for certain repatriated income of a U.S. multinational corporation. This exemption for multinational corporations introduced new concerns of base erosion. As a result, Congress enacted GILTI and retained Subpart F to discourage taxpayers from using intellectual property to shift profits out of the U.S., which could then be repatriated tax-free.

Historically, domestic partnerships have generally been treated as entities for purposes of determining U.S. shareholder and CFC status. Additionally, domestic partnerships have also generally been treated as entities for purposes of treating a domestic partnership as the U.S. shareholder that has the subpart F inclusion with respect to a CFC. Under this pure entity approach, the domestic partnership would determine its own Subpart F inclusion amount, and each partner would take into gross income its distributive share of such amount.

When drafting the proposed regulations for GILTI, the IRS looked to find middle ground, instituting a so called “hybrid approach.” Under this hybrid approach, a domestic partnership is treated as an entity with respect to partners that hold directly, indirectly or constructively less than 10% of any CFCs owned by the partnership, but also treats the partnership as an aggregate for purposes of partners that hold directly, indirectly, or constructively 10% or more with respect to any CFCs owned by the partnership. This confusing mismatch leads to significant uncertainty amongst taxpayers.

THE NEW REGULATIONS

The new regulations are a marked change from both the hybrid approach employed for GILTI and the pure entity approach employed for Subpart F. In this latest guidance, the IRS departs from the traditional approach and hybrid approach described above. Rather, the IRS adopted an aggregate approach when determining a partner’s GILTI inclusion. The IRS also contemporaneously issued proposed regulations that would look to apply the same aggregate approach to Subpart F. These new regulations result in a dramatic paradigm shift in the way U.S. partners in a domestic partnership determine their income inclusions under GILTI and Subpart F.

The new regulation’s aggregate approach moves the determination of the deemed inclusion from the partnership level to the partner level. As a result, only a partner of a domestic partnership that directly, indirectly, or constructively owns at least 10% of the foreign corporation’s stock will be required to include their portion of the CFC’s income under GILTI. While the proposed regulations regarding Subpart F have yet to be finalized, the proposed regulations would also apply the same aggregate approach to the determination of Subpart F. A domestic partnership generally may rely on the proposed rules for tax years of a foreign corporation beginning after Dec. 31, 2017.

The new regulations effectuate this change by treating domestic partnerships as foreign partnerships for certain limited purposes under the tax code. In determining stock owned by a partner in a domestic partnership under Section 958(a), a domestic partnership is treated in the same manner as a foreign partnership. However, the new regulations will not affect determination of ownership under Section 958(a) for any other provision of the tax code. For example, the IRS will continue to treat U.S. partnerships as a U.S. person (and thus an entity) for purposes of determining whether any U.S. person is a U.S. shareholder, or whether a foreign corporation is a CFC. Accordingly, a domestic partnership that owns a foreign corporation is treated as an entity for purposes of determining whether the partnership and its partners are U.S. shareholders, and whether the foreign corporation is a CFC, but the partnership is treated as an aggregate of its partners for purposes of determining whether its partners have inclusions under Subpart F and GILTI and for certain provisions that apply by reference to such regimes.

This sea change to the IRS’s approach could provide tax relief to numerous U.S. partners who would otherwise not be considered U.S. shareholders in a CFC. Although the change in rules generally will not impact partners that hold greater than 10% interests in a partnership’s CFC, they would potentially eliminate inclusions for any partner that fell below this threshold. For diversely held partnerships, such as investment funds, this could be significant. In fact, for investment funds without any 10% or greater partners, this change could eliminate all deemed inclusions.

The impact of these latest regulations minimizes the incentive for investors in private equity groups to organize as a foreign partnership in order to avoid U.S. Shareholder status and subsequently triggering CFC status, thereby triggering the GILTI and subpart F inclusion rules. Taxpayers who are impacted should consider the following proposed actions:

(1) Partnerships that have already filed their income tax return and furnished K-1s should consider amending their return to remove deemed inclusions, when appropriate;

(2) Partnerships that have not filed Form 1065, but have prepared and issued Scheduled K-1s with deemed inclusions should issue updated K-1s consistent with the final regulations; and

(3) Partners that have filed returns based on Schedules K-1s inconsistent with the final or proposed regulations should consider potential refund claims.

It is also critical to note that the aggregate approach may have other indirect effects. For example, the Passive Foreign Investment Company (PFIC) regime may become applicable, as well as other ancillary issues like the determination of previously taxed income and basis. While shareholders may not be subject to Subpart F rules—which would normally take precedence over PFIC rules—the PFIC rules may now apply to the partners’ indirect interest in the foreign corporation. As a result, partners may still be subject to additional current income tax liabilities even if they own less than 10% of a CFC when it is also a PFIC.

CASE STUDY

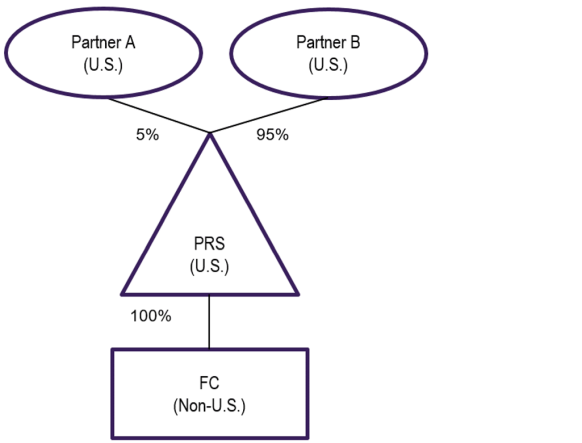

To illustrate the impact of the new regulations, let’s examine a simple fact pattern where a U.S. partnership, PRS, is owned by two partners, Partner A and Partner B. Partner A owns a 5% interest in PRS and Partner B owns a 95% interest in PRS. PRS wholly owns a controlled foreign corporation, FC. FC generated $10M of tested income and $10M of Subpart F income in the current year.

For CFC and U.S. shareholder determinations, PRS is treated as a domestic partnership. Thus, PRS is a U.S. shareholder under Section 951(b), and FC is a CFC under Section 957(a). Partner B is also a U.S. shareholder of FC because it owns 95% of the total combined voting power or value of the FC stock under Sections 958 and 318. Partner A, however, is not a U.S. shareholder of FC because Individual A only owns 5% of the total combined voting power or value of the FC stock under Sections 958 and 318.

For purposes of Sections 951 and 951A, PRS is not treated as owning the FC stock. Rather, PRS is treated in the same manner as a foreign partnership. As Partner B is a U.S. shareholder of FC, Partner B determines its income inclusions under Sections 951 and 951A based on its ownership of FC stock under Section 958(a). In contrast, as Partner A is not a U.S. shareholder of FC, Individual A does not have an income inclusion with respect to FC’s foreign operations. Consequently, Partner B will be required to include $95M of tested income and $95M of Subpart F income. Whereas Partner A would have no deemed inclusions.

The tax impact on non-U.S. shareholder partners under the entity and hybrid approach stands in stark contrast to the impact under the new aggregate approach. Under the entity and hybrid approach, the inclusions with respect to Partner A would be computed at the PRS level, and Partner A would have been allocated $5 million of GILTI and $5 million of Subpart F. The contrast between the old and new regimes demonstrates how favorable the new regulations can be for minority partners. Under the new regulations, Partner A is able to reduce his deemed income inclusion from $10 million to zero.

While this is a basic example, the potential tax implications become more impactful when numerous partners are invested in a partnership. Consider, for example, an investment fund with dozens or perhaps hundreds of partners, none of which own more than 10% of the CFC. Under such a scenario, these partners may be able to reduce their deemed inclusions from millions to zero. The aggregate approach in the new regulations also eliminates the need for costly restructuring that many partnerships were contemplating.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Taxpayers should model and evaluate whether it’s beneficial to amend 2018 partnership returns to remove GILTI and Subpart F inclusions. In some cases, amendments may not be necessary, as superseding returns may be available under Revenue Procedure 2019-32. When doing so, taxpayers should carefully weigh the impact of earlier adopting the proposed regulations applying the aggregate approach to Subpart F computations, including the impact on partners’ capital accounts, PFIC implications, and its direct impact on taxpayer’s distributive share of partnership income.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of The Bureau of National Affairs, Inc. or its owners.

Author Information

Cory Perry is an International Tax Senior Manager at Grant Thornton LLP’s Washington National Tax Office. Vianes Rodriguez of Grant Thornton also contributed to this article.

Learn more about Bloomberg Tax or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

From research to software to news, find what you need to stay ahead.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.