The Internal Revenue Service audits taxpayers who claim the earned income tax credit at a higher rate than most other groups of taxpayers. Kim Bloomquist, former senior economist with the IRS’s Office of Research Operations and research analyst in the agency’s Taxpayer Advocate Service, looks at the explanations offered by the current IRS Commissioner Charles Rettig and suggests there are better ways to return income to low income taxpayers and better uses of IRS resources.

The IRS, for reasons of economic efficiency, is likely to continue to audit earned income tax creditEITC taxpayers more heavily than most other taxpayers even if the agency receives a significant increase in its enforcement budget, based on analysis of government data. The IRS also audits EITC taxpayers at a rate four times higher than non-EITC taxpayers with similar incomes even though in recent years the average additional recommended tax for the latter group is $500 to $2,000 higher. In light of these facts, Congress should consider removing the EITC from the tax code and give it to the Social Security Administration, particularly since the incoming Biden administration has proposed both to strengthen Social Security and allow seniors over age 65 to claim the EITC.

In 2019, Senator Ron Wyden, the ranking member of the U.S. Senate Finance Committee, asked the IRS Commissioner Charles Rettig to explain why EITC filers were more likely to be audited than most other groups of taxpayers.

In a letter response Commissioner Rettig blamed a decade-long decline in the the IRS enforcement budget for the steep drop in audits of high-income taxpayers relative to EITC taxpayers. According to Rettig, budget constraints have made it difficult for the IRS to hire and retain higher-graded, experienced examiners typically assigned to audit high-income taxpayers. Moreover, he explained, the IRS cannot simply shift lower-graded examiners to audit the more complex tax returns of the wealthy because such employees lack the requisite experience and skills. Rettig concludes his letter stating that the IRS won’t significantly change its audit policy without an increase in its budget and that it must maintain an audit presence among all income groups, including EITC. In short, the IRS admits it is auditing EITC claimants at higher rates than all but the very rich, but they want us to believe it’s not because they’re being unfair to this group of taxpayers.

In this article, I show why the IRS, for reasons of economic efficiency, is likely to continue to audit EITC taxpayers more heavily than most other taxpayers even if the agency receives a significant increase in its enforcement budget. I also show that the IRS audits EITC taxpayers at a rate four times higher than non-EITC taxpayers with similar incomes even though in recent years the average additional recommended tax for the latter group is $500 to $2,000 higher. In light of these facts, I conclude that Congress should consider removing the EITC from the tax code and give it to the Social Security Administration, particularly since the incoming Biden administration has proposed both to strengthen Social Security and allow seniors over age 65 to claim the EITC.

In its 2019 Databook the IRS changed reporting of operational audits from a fiscal year basis to a tax year basis. The IRS states that the main reason for the change is to improve transparency. For example, the IRS assumes that most audits begun during a fiscal year were primarily returns filed for the immediately preceding tax year (e.g., fiscal year 2018 audits represented tax returns for tax year 2017). While this assumption holds for the majority of cases, audits of many high-income taxpayers, especially in recent years, are not started in the year following the filing year but often two or more years later. This is evident in the 2019 Databook, which shows only seven audits of tax year 2018 tax returns of taxpayers with total positive income (TPI) of $10 million or more were closed or in process by the end of the first quarter of fiscal year 2020 (that is of Dec. 31, 2019). However, a disadvantage of reporting audit data by tax year is that several years of data are needed before we get a reasonably accurate count of the total number of audits performed. It is for this reason I limit my analysis in this article to tax years 2010 through 2015, even though the 2019 Databook includes (preliminary) data for tax year 2018.

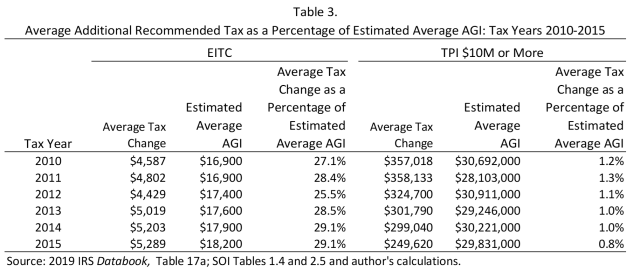

The IRS finds EITC tax audits attractive to perform in several respects. First, they require few hours to work and are closed quickly. According to Commissioner Rettig, the average time to close an EITC audit is five hours versus an ‘average’ of 61 to 251 hours for audits of tax returns with TPI of $10 million or more. If we assume the total number of hours to complete an audit of high-income taxpayers is closer to 250 hours, then the hourly return on investment for audits of both groups of taxpayers is about the same; i.e., $1,000 per hour (see Table 3 below). Moreover, because the hourly labor cost for GS-8 tax examiners is less than GS-14 revenue agents, the return per dollar of labor cost is probably higher for EITC audits. Therefore, from a business case perspective EITC audits are ‘profitable’ for the IRS to conduct. However, the mission statement of the IRS doesn’t mention anything about economic efficiency. It states:

Provide America’s taxpayers top-quality service by helping them understand and meet their tax responsibilities and enforce the law with integrity and fairness to all.

Perhaps the IRS interprets the term ‘fairness’ to include the goal of maximizing the return per dollar expended since tax dollars fund the agency’s operations. It would be helpful if the IRS defined what it views as fair (and unfair) treatment of taxpayers.

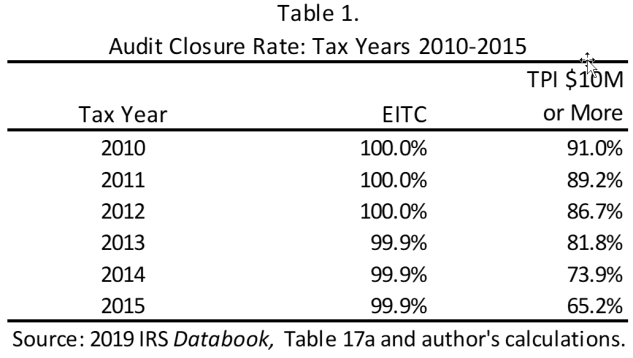

Table 1 shows the audit closure rates for EITC taxpayers and taxpayers with TPI of $10 million or more. The data used to calculate these rates represents audit status as of Sept. 30, 2019. Table 1 clearly shows that nearly all EITC audits are resolved quickly, but more than a third of tax year 2015 audits of high-income filers remains open. Moreover, nearly a decade after the returns were due to be filed 9% of tax year 2010 high-income audits were still open. The difference in closure rates between these two groups highlights the gap in the degree of due process available to the rich versus the poor.

TABLE 1

The risk scoring algorithms the IRS uses to identify potential taxpayers to audit selects tax returns with the highest potential noncompliance. Since EITC audits have a high probability of obtaining a positive tax change this group of taxpayers perennially tends to be selected for an audit.

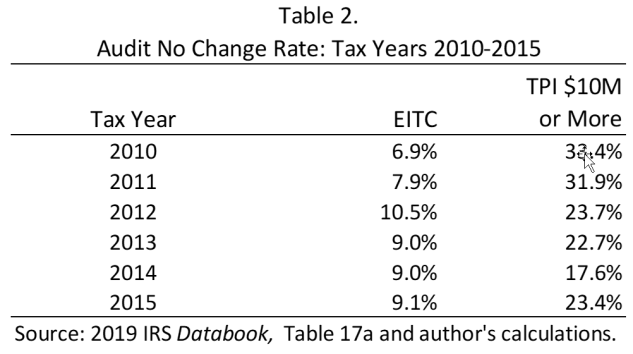

Table 2 shows that in tax year 2015, 9.1% of EITC audits were closed with no tax change compared to a no change rate of 23.4% of audits for tax returns with TPI of $10 million or more. Table 2 also shows us that as time passes the percentage of no change high-income tax returns actually increases to 33.4% whereas the percentage of no change EITC audits decreases to 6.9%. The widely divergent audit outcomes between rich and poor taxpayers suggests either that the IRS does a poor job of selecting high-income audit cases or that the IRS just gives up trying to enforce the law the longer rich taxpayers can drag out the process. On the other hand, it appears that EITC filers are more likely to “throw in the towel” as time passes. It would be interesting to hear from the IRS their interpretation of the data in Table 2.

A third possible reason why the IRS favors auditing EITC taxpayers is the “salience” factor. I define audit salience as the financial impact of an audit on a taxpayer. I calculate this measure for a group of taxpayers as the average additional recommended tax change as a percentage of estimated average adjusted gross income (AGI). (For EITC taxpayers I calculate average AGI for tax returns with AGI between $1 and $50,000 using SOI Table 2.5. Similarly, for taxpayers with AGI of $10 or more I use data in SOI Table 1.4.) Table 3 presents this salience measure for EITC taxpayers and taxpayers with TPI of $10 million or more.

Table 3 shows that for EITC taxpayers the average tax change recommended from an audit represents between 25% and 30% of the average EITC taxpayer’s AGI. Such a large impact can make a significant impression and may discourage taxpayers from ever claiming the EITC again (justified or otherwise). On the other hand, the impact of an audit on wealthy taxpayers represents only about 1% of average AGI. While not inconsequential, the small size of the average recommended tax change relative to average AGI is less likely to change the compliance behavior of the wealthy.

Finally, Commissioner Rettig justified the current the IRS audit policy toward EITC taxpayers as necessary to maintain adequate audit coverage. In general, most would agree that it is important to provide audit coverage of all taxpayers. However, the Commissioner doesn’t tell us what a desired or even minimum audit presence should be for any group of taxpayers or one group of taxpayers relative to another.

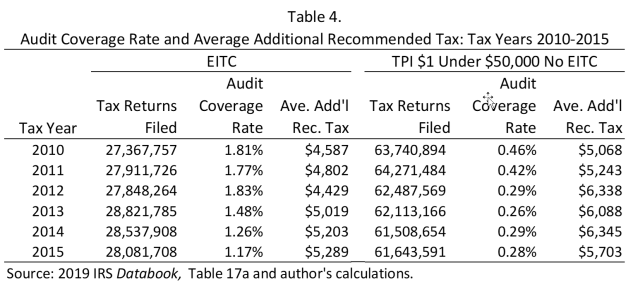

Table 4 compares the audit coverage and average additional recommended tax for EITC taxpayers and taxpayers who didn’t claim the EITC but whose reported incomes are similar (between $1 and $50,000 TPI). Since nearly all EITC taxpayers have AGI less than $50,000, I subtract the number of EITC audits from audits of taxpayers with TPI between $1 and $50,000. I do the same for additional recommended tax. Average additional recommended tax is calculated as total additional recommended tax (estimated for non-EITC filers) divided by the number of closed audits less the number of no change audits.

During tax years 2010 to 2015 the audit coverage rate of EITC taxpayers was four times that of non-EITC taxpayers. It is also worth noting that in all six years the average additional recommended tax was higher for non-EITC taxpayers. If the IRS believes it is important to maintain adequate audit coverage for all taxpayers, then are EITC taxpayers being over-targeted for audit or are non-EITC taxpayers with similar incomes being under-targeted? The latter seems more likely. It appears that the IRS could have assigned more examiners to non-EITC taxpayers and collected more tax. The IRS should explain why it makes sense to audit EITC taxpayers at a rate four times greater than taxpayers with similar incomes when they apparently could increase collections by shifting examiners from one group of taxpayers to another similar group.

Conclusion

The IRS audits EITC filers more intensely than all but the wealthiest taxpayers but says it is not being unfair to the former. In this article, I have presented evidence that shows why the IRS might consider EITC audits a good “business” decision in the face of significant budget cuts. EITC audits can be conducted at little cost, are closed quickly, and have a low no change rate. Moreover, EITC audits are highly salient to taxpayers because the additional recommended tax change averages 25% to 30% of AGI and is likely to cause audited taxpayers to stop claiming the EITC, whether justified or not. While perhaps a good business decision, the IRS mission statement says nothing about economic efficiency, but instead emphasizes integrity and fairness. The IRS should explain how its current audit policy conforms to its stated agency purpose.

The IRS says it is unwilling to make significant changes to its audit policy because it must maintain adequate audit coverage, including on EITC filers. However, using published the IRS data I show that IRS audits EITC filers at a rate four times higher than non-EITC filers with similar incomes. the IRS should explain how it justifies such different audit coverage rates for similar groups of filers, particularly when the average additional recommended tax for the non-EITC group is $500 to nearly $2,000 dollars higher.

For years the IRS has been unable to show any measurable change in compliance behavior by EITC filers despite relatively intense auditing and other enforcement efforts. Moreover, it will be several more years before the IRS knows if the delay in issuing EITC-related refunds mandated by the Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes Act of 2015 (PATH Act) is having any effect. Perhaps it is time for Congress (and the incoming Biden Administration) to consider removing the EITC (and related tax credits, like the Additional Child Tax Credit) from the tax code and giving it to an agency, like the Social Security Administration, that manages other income support programs. This would remove the temptation by the IRS to use EITC taxpayers to bolster its enforcement numbers and turn its focus instead toward taxpayers that account for the majority of the tax gap, like business filers in the top quintile of AGI.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of The Bureau of National Affairs, Inc. or its owners.

Author Information

Kim Bloomquist, currently retired, previously worked as a senior economist in the IRS Office of Research from 1999 to 2015 and as an operations research analyst in the Taxpayer Advocate Service from 2015 to 2018.

Learn more about Bloomberg Tax or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

From research to software to news, find what you need to stay ahead.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.