- Political shift sets up agenda overhaul for regulator

- Leadership changes could leave board in limbo for months

The pending political transition in Washington is poised to put the US audit watchdog and its agenda in limbo, scuttling efforts to rewrite its outdated rulebook and upending the regulator’s priorities.

Auditors anticipate the shift from Democrats to Republicans will result in a regulator that’s more open to industry concerns and input. Investors, however, are bracing for what could be a sharp slowdown in the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board’s activity, from disciplining wayward auditors to routine checks of their work.

“The PCAOB is most effective when it is active,” said Robert Pawlewicz, an accounting professor at the University of Richmond.

President-elect Donald Trump’s administration, starting Monday, is expected to broadly scale back regulations and downsize government agencies. Those efforts could extend to the PCAOB, an independent entity under the oversight of the Securities and Exchange Commission.

The SEC approves the audit board’s budget, appoints its members, and signs off on changes to its regulations and standards before they can take effect. Appointing a new PCAOB chair to replace Erica Williams could derail the board’s ambitious agenda of overhauling aging rules and raising the bar for audits.

Deeper changes could come through replacing other board members and division directors, though that process could take months.

A Republican-controlled Congress could also target the PCAOB for elimination—handing its responsibilities to the SEC.

“Even if Republican lawmakers are unable to completely shut down the PCAOB, they could grind it to a halt by appointing a PCAOB chair who simply stalls action and trims staff,” Pawlewicz said.

Congress created the watchdog as a nonprofit, in part to shelter it from politics and the audit industry after accounting scandals that toppled Enron Corp. and WorldCom Inc. However, the past two administrations have replaced the PCAOB’s leadership, tethering its policies to the party controlling the White House.

Paul Atkins, Trump’s pick for SEC chair, sought to rein in the board during his earlier tenure on the commission. He’s expected to name his own PCAOB chair, setting up another policy pivot.

Standard-Setting Uncertainty

Last year was the board’s most productive since its inaugural year, completing seven rule updates.

The PCAOB did not respond to questions about Williams’ future plans or how the incoming administration could reshape her agenda. In a statement, however, the board said it remains focused on protecting investors and driving audit quality through its inspections, enforcement, and standard-setting work.

Williams, whose five-year term ends in 2029, oversaw the launch of the PCAOB’s first-ever inspections of audit firms in China and Hong Kong and a review of audit firm culture.

Trump’s re-election has already derailed a controversial proposal to expand how auditors consider the toll of their clients’ lawbreaking on their financial results. The board said in late November it would not finalize its overhaul of the standard, known as non-compliance with laws and regulations, until it consults with the SEC’s new leadership.

Trump’s SEC also is now set to decide whether a separate pair of PCAOB rules that would expand auditor disclosures should take effect. Earlier this week, the commission under outgoing SEC Chair Gary Gensler opted to extend its review timeline for the proposals.

The projects aren’t likely to receive a warm reception from Republican members of the SEC, who previously challenged the board’s overall approach to standard-setting and enforcement.

The audit industry opposes both the expanded obligations for assessing their clients’ possible crimes and the reporting requirements.

Seeking feedback from diverse stakeholders and relying on data to inform standard-setting are key to effective oversight, the Center for Audit Quality said in a statement.

“A robust regulatory framework is a necessary component to audit quality and investor confidence,” said the group, which represents the interests of auditors.

Investor and consumer advocates, however, were frustrated that the PCAOB couldn’t complete a rewrite of the board’s illegal acts standard to shed more light on risks that could threaten public company share values.

“The incentives in the industry are to keep your clients. And making the audit more difficult or more invasive, that’s a tough sell,” said Alex Martin, policy director for climate finance with Americans for Financial Reform, which seeks a more equitable finance system.

Enforcement Pivot

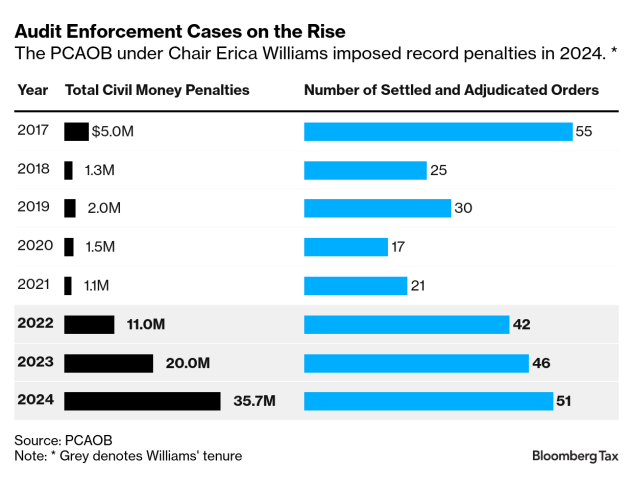

The board has taken an aggressive enforcement stance under Williams, a posture that is unlikely to shift without a change in PCAOB leadership.

Enforcement penalties have more than tripled since the 2022 start of Williams’ tenure and hit a record $35.7 million last year. Last year’s total included a $25 million fine against KPMG’s Dutch affiliate, the largest penalty in the board’s history, for ethics lapses related to widespread cheating on internal training.

In addition to the administration change, a June Supreme Court ruling on agency enforcement could also blunt the board’s strategy, bringing down the cost of violations and the number of settled cases, said Michael Plotnick, a partner at King Spalding LLP and a former PCAOB chief trial counsel.

Under new leadership, the board would likely turn its focus to serious violations but without the steep penalties common under Williams, Plotnick said.

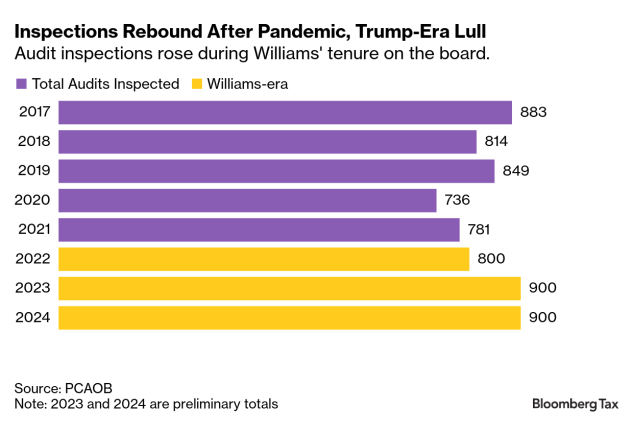

Board watchers worry that the next chair may opt to scale back inspections scrutiny, selecting fewer firms and audits to review each year.

That would follow the board’s playbook under former PCAOB Chair William Duhnke, appointed in 2017 by the first Trump administration, said Pawlewicz, the Richmond professor.

But inspections could resume their traditional place as the board’s primary tool to oversee the work of auditors, ensuring they meet basic standards while spending fewer resources on enforcement and rule-writing. It all depends on who serves on the board.

“I hope they really put people in that support the mission because that hasn’t always been the case in the past,” said Preeti Choudhary, accounting professor at the University of Arizona. “That really brings down the morale of the organization and it really becomes a huge step back.”

To contact the reporter on this story:

To contact the editors responsible for this story:

Learn more about Bloomberg Tax or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

From research to software to news, find what you need to stay ahead.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.