- Mayer Brown partner examines potential risks with acquired IP

- An intra-corporate licensing structure needed for full IP use

In any merger-and-acquisitions deal involving intellectual property, the acquiring company must establish a post-closing, intra-corporate licensing structure to fully use the newly acquired IP. But in doing so, the company likely will encounter two major risks.

First, a post-closing licensing structure can create an increased tax risk, particularly if it involves cross-border licenses. Second, a poorly drafted licensing structure can compromise a company’s ability to enforce the acquired IP.

These risks underscore the importance of assessing—before closing—the tax and IP issues that arise from a post-closing licensing structure for IP acquired in an M&A deal.

IP Integration

A target company’s IP portfolio can be a major motivator in M&A deals. In these cases, the acquiring company generally seeks to integrate the newly acquired IP so it can sell new products, license new technologies, or conduct new lines of research.

To achieve these goals, an acquiring company must implement an intra-corporate licensing structure that conveys the acquired IP to the proper affiliates. The parent must first decide which affiliate will own the IP and then determine what kinds of licenses will be given to other affiliates.

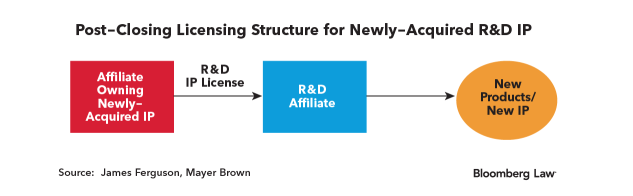

These issues usually depend on the IP’s nature and purpose. For example, if the IP relates to a new research platform, the parent may want to license the IP to a research-and-development affiliate so it can use the platform to generate new products and IP:

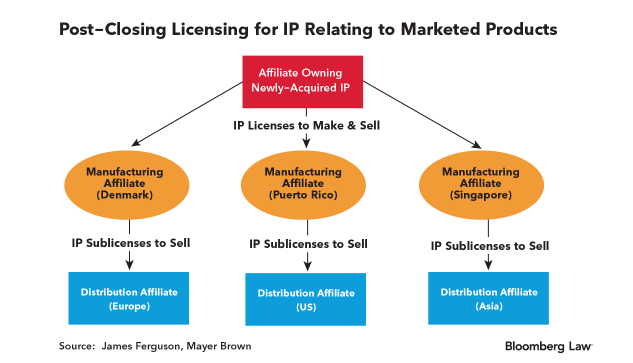

But if the new IP relates to currently marketed products, the acquiring company may want to give its manufacturing affiliates the right to make the products, while sublicensing the right to sell the products to distributors in different jurisdictions.

Such post-closing licensing structures are essential to enable the entire corporate organization to use, enforce, and sublicense the acquired IP. Yet the structures also pose risks of their own.

Tax Risks

A post-closing licensing structure can create significant tax liabilities, particularly if they involve affiliates in different jurisdictions and raise transfer pricing issues. Tax authorities in a growing number of countries have claimed that acquiring companies are subject to an exit tax because their licensing structure “transferred” the IP rights of a newly acquired subsidiary to a foreign affiliate.

In making this claim, the tax authorities often rely on a key distinction in tax law between the legal IP owner—the affiliate holding legal title—and the economic IP owner—the affiliate bearing the greatest economic risk in developing or using the IP.

To determine the economic owner, many tax authorities use factors of Development, Enhancement, Maintenance, Protection and Exploitation, or DEMPE. An affiliate may be deemed the economic owner of certain IP (and therefore subject to greater tax liability) if it controls the development, exploitation, or protection of the IP.

By relying on DEMPE, a tax authority can claim that an acquiring company “transferred” the IP of a newly acquired subsidiary to a foreign affiliate even though the subsidiary still retains legal title to the IP.

A pre-closing assessment of the tax risks arising from a proposed post-closing licensing structure may reveal ways to revise the structure to reduce tax risks while, at a minimum, enabling the company to include any projected tax liability in the costs of the transaction.

IP Risks

A post-closing licensing structure is essential to convey the appropriate rights to the proper affiliates and enforce such rights against third-party infringers. The nature of the necessary licenses will depend on the nature of the underlying IP.

Patents. For patent-protected products, a key goal of the licensing structure should be granting exclusive patent rights to affiliates that are in fact selling the products. This issue arises from the requirements of standing for patent enforcement actions against third-party infringers.

In the US, an affiliate lacks standing to join such an action unless it owns the patent or is an exclusive licensee. If the selling affiliate is a non-exclusive licensee, as is often the case in tax-driven structures, it will have no standing to join the lawsuit. This is important because a company generally can’t recover lost profits or obtain an injunction if the affiliate selling the patented product has no standing to join the lawsuit.

The patent-owning affiliate can still bring an infringement action (because it owns the patent), but it can’t recover lost profits unless it actually sells the patented products. The post-closing licensing structure must vest the US selling affiliates with an exclusive patent license to sell the patented product.

Trade secrets. If the newly acquired IP includes trade secrets, the licensing structure must ensure that the trade secrets can be protected and enforced. Only the owner of a trade secret can bring a civil action under the Defend Trade Secrets Act, but any party with lawful possession can bring a common law action for misappropriation. The acquiring company must decide what entity will own the new trade secrets and what entities will be the licensees.

To ensure enforceability, the trade secret licenses must impose specific obligations on the licensees to protect the data’s confidentiality, such as restricting employee access and use of the data.

Trademarks and copyrights. If the new IP includes trademarks or copyrights, the post-closing licensing structure will need to identify what entity will be the registered owner of the marks or copyrights, and what entities will be licensees.

The registered owner in each jurisdiction generally will have standing to enforce the mark or copyright in that jurisdiction. In the US, an exclusive trademark licensee may also have standing, depending on the rights granted by the underlying license.

Thus, as with the tax risks, the IP risks arising from post-closing licensing structures show the importance of reviewing such structures before closing to mitigate the risks and reduce the costs of the transaction.

This article does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg Industry Group, Inc., the publisher of Bloomberg Law and Bloomberg Tax, or its owners.

Author Information

James R. Ferguson is partner with Mayer Brown focusing on IP litigation and intra-corporate IP licensing structures.

Write for Us: Author Guidelines

To contact the editors responsible for this story:

Learn more about Bloomberg Tax or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

From research to software to news, find what you need to stay ahead.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.