John Barlow, a partner in Baker McKenzie’s Washington DC office, examines how recent R&D changes in OBBBA are having material collateral impacts on CAMT and various international provisions.

The R&D provisions in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) have quickly become the number one issue for many corporate tax departments. OBBBA helpfully reintroduced immediate expensing for domestic R&D activities under new §174A to jumpstart economic growth. Nevertheless, some taxpayers are seeing a drastic drop in taxable income that is creating adverse tax results, especially in R&D-intensive industries.

In particular, many taxpayers are now faced with owing CAMT and BEAT due to excessively large R&E deductions caused by the “doubling up” of (1) immediately deductible domestic R&E expenditures in 2025 and thereafter and (2) the continued amortization of previously capitalized R&E expenditures. These doubled-up R&E deductions are also creating overall domestic losses (ODLs) under §904, and some taxpayers are losing their deductions for GILTI/NCTI and FDII under §250(a)(2) and the contentious §246(b).

This article explores the various issues that these unlucky taxpayers are facing from the combined impact of immediate domestic R&E expensing and the continued amortization of previously capitalized R&E expenditures. In addition, this article addresses several other OBBBA changes to R&E, including: clarifications to foreign R&E capitalization under §174 and §1016 as well as changes to the R&D credit provisions and §280C(c).

I. Doubling Up on R&E

Overview

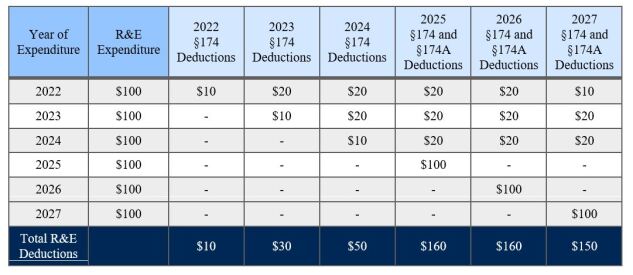

New §174A allows taxpayers to once again expense domestic R&E expenditures that are incurred in tax years beginning after December 31, 2024. In addition, taxpayers will continue to recognize amortization deductions for R&E expenditures that were capitalized under §174 between 2022 and 2024. The result is that taxpayers may have aggregate R&E tax deductions in 2025, 2026, and 2027 that are ~60% larger than their actual R&E expenditures for those years. The chart below illustrates how these large R&E deductions can arise, focusing in particular on domestic R&E.

Some taxpayers will welcome these large R&E deductions. However, for taxpayers in R&D-intensive industries, this doubling-up is causing too large a drop in taxable income that leads to permanent tax costs. While reduced taxable income is normally a good thing, numerous code sections create adverse tax consequences when a taxpayer’s US taxable income decreases to such a dramatic extent. As a result, taxpayers are now having to model whether they need to elect to capitalize current-year domestic R&E expenditures under §174A(c) and §59(e) in order to prevent permanent, adverse consequences under CAMT, BEAT, §904, §250(a)(2), and §246(b).

CAMT Scaries from Doubling up on R&E

The most pressing issue for many taxpayers is whether the doubling up of R&E deductions will cause them to owe CAMT in 2025 and perhaps several years thereafter. In general, a taxpayer owes CAMT when 15% of the taxpayer’s applicable financial statement income (AFSI) reduced by foreign tax credits is greater than the taxpayer’s regular tax liability reduced by foreign tax credits. One of the primary problems that taxpayers face is that R&E amortization deductions for expenses that were previously capitalized in 2022 to 2024 and that are still being amortized only reduce a taxpayer’s regular taxable income in 2025 and thereafter. Those amortization deduction do not decrease the taxpayer’s AFSI in those later years. Thus, in 2025 and thereafter, a taxpayer’s AFSI may be much higher than a taxpayer’s regular taxable income. As a result, this layer of R&E amortization deductions from prior years could cause many taxpayers to owe CAMT, unless the taxpayer takes actions to increase its regular taxable income.

Compounding the pain, many taxpayers are quickly learning that CAMT tax credits, which become available after paying CAMT, are effectively worthless. In particular, taxpayers in R&D-intensive industries that take large R&D credits are often prevented from ever using their CAMT tax credits and have to record valuation allowances against their CAMT tax credits. This is because §53(c) provides that a taxpayer can only use a CAMT tax credit to the extent that the taxpayer’s tentative minimum tax for the year is less than the taxpayer’s regular tax liability reduced by R&E and other non-CAMT tax credits. Many taxpayers that engage in extensive R&E activities will be in a situation where their R&D credits will always cause the §53(c) limitation to apply because: (1) their tentative minimum tax calculation will always be greater than (2) their regular tax liability reduced by R&D credits. (It should be noted that, even though a taxpayer is prevented from claiming a CAMT tax credit under §53(c), the taxpayer may still not owe CAMT because CAMT is only owed to the extent the taxpayer’s tentative minimum tax exceeds a taxpayer’s regular tax liability unreduced by R&E and other credits. Compare §§55(a)(2) & (c) with §53(c)(1).)

As a result, taxpayers that will always be subject to the §53(c) CAMT credit limitation must take actions to avoid paying CAMT in the first instance. In particular, many taxpayers are now modeling whether they need to make elections under §174A(c) or §59(e) to capitalize R&E expenditures, in order to prevent CAMT from being owed and the receipt of useless CAMT tax credits. Consequently, taxpayers may choose to postpone or even forgo some R&E activities if they cannot immediately expense those costs because of the threat of a CAMT liability. This perverse situation appears to be directly contrary to Congress’s intent in enacting §174A—i.e., to immediately stimulate economic growth through domestic R&E activities.

BEAT Issues from Doubling-Up on R&E

Doubling-up of R&E has created challenges as well as opportunities under the BEAT provisions. Some taxpayers will benefit from the increased R&E deductions that result in a larger denominator that makes it less likely that a taxpayer will cross the 3% base erosion percentage, such that BEAT will not apply to that taxpayer. See §59A(c)(4). However, if a taxpayer is going to be an applicable BEAT taxpayer (because the taxpayer will definitely pass the 3% base erosion percentage), then the doubling-up of R&E expenditures can cause the taxpayer to owe additional BEAT tax because the doubled-up R&E expenditures may reduce the taxpayer’s regular tax liability by such a large amount. See §59A(b)(1). This is most likely an issue for inbound companies.

Lost §250 Deductions from Doubling-Up on R&E

Taxpayers are also monitoring whether the doubling up of R&E deductions causes them to lose their §250 deductions for GILTI and FDII for two reasons. First, §250(a)(2) prevents taxpayers from taking a §250 deduction to the extent that (1) a taxpayer’s GILTI and FDII income exceeds (2) the taxpayer’s overall taxable income. The doubling up of R&E deductions is causing many taxpayers to have such large losses that the §250(a)(2) limitation is now coming into play.

Second, §246(b) may also come into play to limit a taxpayer’s §250 deductions that are attributable to a taxpayer’s §78 gross-up for GILTI foreign tax credits. The IRS has published GLAM 2024-002, which applies a controversial interpretation of §246(b). If the principles of this GLAM were to apply, then many taxpayers may lose additional §250 deductions to the extent the taxpayer has losses from US operations (including US shareholder R&E deductions) that do not create a NOL.

How can a taxpayer prevent these §250(a)(2) and §246(b) issues? You guessed it. Taxpayers are already modeling whether they need to make §174A(c) or §59(e) elections to ensure that these limitations do not apply.

Foreign Tax Credit Limitation Issues from Doubling-Up on R&E

The doubling up of R&E expenditures could also cause some taxpayers to have an ODL that reduces their §904 FTC limitations. In general, a taxpayer has an ODL if the taxpayer has net US source losses. Normally, the effect of an ODL is that the ODL reduces a taxpayer’s §904 limitation in its GILTI and other foreign source baskets. See §904(f)(5)(D). As a result, a taxpayer with an ODL may actually owe US tax on its GILTI inclusion – even though that GILTI income was subject to a high rate of foreign tax.

Before OBBBA, it was clear that a US taxpayer’s R&E deductions could create an ODL that reduced the taxpayer’s GILTI FTC limitation. However, OBBBA amended §904(b)(5) to provide that a US shareholder’s R&E expenditures are no longer allocated and apportioned to (and thus no longer reduce) a taxpayer’s GILTI FTC limitation. In light of this change, does it make sense for an ODL comprised of a US shareholder’s R&E deductions to reduce a taxpayer’s GILTI FTC limitation? Nevertheless, until Treasury addresses the ODL and SLL issues that are arising from R&E deductions, many taxpayers are once again looking at capitalizing their current year domestic R&E expenditures to avoid creating an ODL.

Elective Capitalization under §174A(c) and §59(e) to Avoid Doubling-Up on R&E

The discussion above assumes that taxpayers can make elections to capitalize domestic R&E expenditures under §174A(c) and §59(e) to mitigate the adverse application of the provisions discussed above.

However, many open questions exist on how taxpayers make these capitalization elections. For example, many taxpayers expect to continue capitalizing R&E expenditures on a project-by-project basis, rather than capitalizing all of their R&E expenditures. In addition, taxpayers need to determine the period over which to amortize the capitalized R&E expenditures. Based on the previous discussion in this article, taxpayers can expect to see lots of developments on these issues in the near future.

It also bears mentioning that, starting in taxable years after December 31, 2025, taxpayers will no longer have an incentive to capitalize domestic R&E expenditures to increase FDII deductions. Under prior law, some taxpayers obtained effective tax rate benefits for accounting purposes from the capitalization of R&E expenditures because capitalization resulted in (1) a deferred tax asset from capitalized R&E expenditures, which was booked at the normal 21% corporate tax rate, and (2) a higher §250 deduction because the taxpayer had fewer expenses to allocate to FDDEI income. However, OBBBA modified the FDII expense apportionment rules in §250(b)(3)(A)(ii) so that R&E expenditures are no longer allocated to FDII after 2025. As a result, starting next year, taxpayers will not get a FDII benefit from capitalizing R&E, except to the extent that capitalization is needed to avoid a haircut under §250(a)(2). That being said, some contract R&E service providers may seek §174 treatment for their costs under Notice 2023-63 so that those providers do not have to allocate their R&E service costs to FDDEI.

Most Taxpayers Benefit from §174A

It is worth repeating that not all taxpayers will suffer from the issues described above, and the doubling-up of R&E expenditures will be a boon for those taxpayers.

In addition, many taxpayers may want to make an election to accelerate the deduction of their previously capitalized R&E expenditures into 2025 and 2026. See OBBBA, §70302(f)(2). However, before a taxpayer can make this election, it will need to analyze the collateral impact of that election under all of the provisions discussed above. Thus, whether taxpayers can make an acceleration election that avoids the issues described above will depend on one thing: that dang model.

II. Other OBBBA R&D Changes

OBBBA also made numerous other changes to the R&E provisions, several of which are discussed below.

Changes to §1016 and §174

While OBBBA allows taxpayers to immediately expense domestic R&E expenditures, OBBBA still requires taxpayers to capitalize foreign R&E expenditures and amortize them over a 15-year period. Nevertheless, OBBBA made some intriguing changes to §1016 and §174(d) for these capitalized foreign R&E expenditures.

In particular, §1016 is entitled “Adjustments to basis”, and §1016(a)(14) now provides that “proper adjustments in respect of property shall in all cases be made…for amounts allowed as deductions under section 174 or 174A(c).” In addition, §174(d) was amended to increase a taxpayer’s amount realized upon the disposition of intangible property, when that intangible property arose from capitalized foreign R&E expenditures. Section 174A contains no provision similar to §174(d) for domestic R&E expenditures capitalized under §174A. These new provisions support taxpayer positions that are in part based on the argument that the basis of intangible property is adjusted for amounts capitalized under §174 and §174A. Additional developments in this area are expected.

R&D Credit Changes

Finally, OBBBA makes two changes to the R&D credit provisions. First, amended, §41(d)(1)(A) now allows a credit “with respect to which expenditures are treated as domestic research or experimental expenditures under section 174A.” Previously, §41(d)(1)(A) applied to expenditures that “may be treated as specified research or experimental expenditures under section 174."It is not clear that Congress intended for this amendment to change which R&E expenditures qualify for R&D credits, other than specifying that only expenditures under §174A now qualify.

Second, OBBBA amended §280C(c) so that a taxpayer must reduce its R&E expenditures that can be capitalized under §174A(c) when the taxpayer claims a §41 R&D credit. The plain language of former §280C(c) had not required a taxpayer to reduce its capitalized R&E expenditures as long as the taxpayer’s §41 credits for the year did not exceed the taxpayer’s “amount allowable as a deduction for such taxable year” for qualified research expenditures. In general, a taxpayer’s R&E amortization deduction for R&E expenditures during the year would have been equal to 10% of the taxpayer’s total domestic R&E expenditures during the year due to the mid-year convention under §174(a). See former §174(a).

In Notice 2023-63, the IRS had asked for comments on how to interpret former §280C(c). Numerous taxpayers submitted comments pointing out that Treasury did not have the authority to override the plain language of §280C. It is not clear whether Treasury will follow those comments. However, if those comments are ignored, then Treasury can expect fights from taxpayers on this issue. Interestingly, OBBBA provides that the amendments to §280C were not intended to create any inference on the interpretation of former §280C(c).

This article does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg Industry Group, Inc., the publisher of Bloomberg Law, Bloomberg Tax, and Bloomberg Government, or its owners.

Author Information

John Barlow is a partner in Baker McKenzie LLP’s Washington, DC office.

The author would like to thank Ethan Kroll, Paula Levy, Erik Christensen, and Liz Boone for their helpful comments.

Write for us: Author Guidelines.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Soni Manickam at smanickam@bloombergindustry.com

Learn more about Bloomberg Tax or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

From research to software to news, find what you need to stay ahead.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.