As the SEC scrutinizes all facets of executive compensation, undisclosed executive perks continue to be in its enforcement crosshairs, Jones Day’s David Peavler and Evan Singer say.

Over the last decade, the Securities and Exchange Commission has brought 20 enforcement cases against public companies for not properly disclosing perks provided to executives—including two last year.

The SEC’s expansive view of what constitutes a perk—and the low-dollar thresholds for disclosure—can make it challenging for companies to identify, quantify, and fully describe them. But failing to disclose perks can be expensive, as companies may face significant costs to investigate, defend, and remediate problematic disclosures and internal controls. And the SEC often imposes sizable financial sanctions when faulty disclosures come to light.

To help reduce the risk of undisclosed executive perks, we’ve identified those that most often lead to SEC enforcement actions, as well as practical steps companies can take to strengthen relevant internal financial and disclosure controls.

Perks Definition

Agency guidance indicates the SEC considers everything provided to an executive that includes a personal aspect to be a perk unless it’s either “integrally and directly related to the performance of the executive’s duties” or “available on a non-discriminatory basis to all employees.”

The SEC views “integrally and directly related” narrowly, supplying as examples only obvious items such as smartphones and laptops. Critically, something being business-related doesn’t mean that it’s integrally and directly related to the executive’s duties.

Low-Dollar Thresholds

The risk posed by the SEC’s broad view of executive perks is compounded by the low-dollar thresholds for disclosure. Issuers must disclose the total value of perks and other personal benefits provided to named executives who receive at least $10,000 of such items during the year, identifying each perk by type.

Each perk that exceeds the greater of $25,000 or 10% of the total amount of perks for that officer must be specifically quantified and disclosed in a footnote. In an era of rapidly rising costs, these thresholds are likely to capture a wide range of executive benefits.

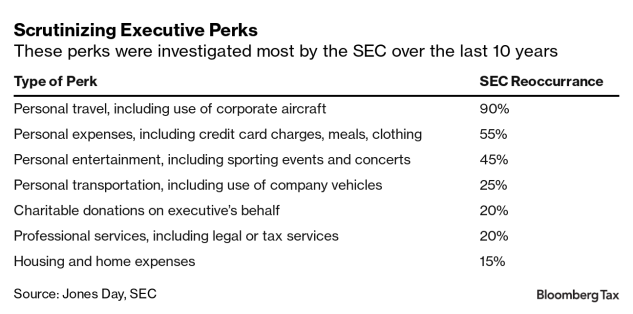

Common Undisclosed Perks

Personal travel is the perk most frequently flagged by the SEC, appearing in all but two cases in the last 10 years. Most of those cases involved travel on commercial or chartered aircraft for vacations, sporting events, or other personal activities. Personal use of a company owned or leased aircraft came up in seven cases.

In those situations, the SEC requires a company to report the “aggregate incremental cost” of the executive’s personal use of the aircraft—that is, the direct operating cost attributable to the personal travel. In one case, the SEC faulted a company for disclosing the taxable value of its executives’ personal use of company aircraft, rather than the aggregate incremental cost—a much higher figure.

Several cases involved undisclosed payments for family and friends to accompany an executive to business events, such as a board meeting to which directors’ spouses were invited or to customer and industry receptions.

Not all the travel in these cases had an obvious personal purpose. In one case, a company reimbursed its CEO for flights to attend entertainment events sponsored by a company supplier. But in the SEC’s view, merely having a connection to the company’s business wasn’t enough to justify nondisclosure, because the travel wasn’t integrally and directly related to the executive’s duties.

This narrow standard can be difficult to meet, especially when trips entail unmistakably personal components, such as an accompanying spouse or entertainment activities such as concerts and sporting events.

Other Perks

Undisclosed payments for meals, clothing, club memberships, and event tickets also have drawn enforcement scrutiny, even when they involved business-related elements. For example, one company reimbursed its CEO for conducting “site inspections” of potential venues for an upcoming company conference.

The SEC alleged those reimbursements included payments for luxury accommodations, meals, entertainment, off-site excursions, and travel costs for the CEO’s friends, which the SEC deemed disclosable because they weren’t integrally and directly related to the CEO’s duties.

Mitigating Risk

To minimize SEC enforcement risk, companies might consider:

Applying the right standard for assessing perks. Ensure policies, controls, and procedures are calibrated to the SEC’s narrow integrally-and-directly-related standard. Don’t mistake being business-related as sufficient to justify nondisclosure.

Scrutinizing travel expenses. All executive travel expenses borne by the company—including use of company aircraft, vehicles, and other assets—should be analyzed to confirm they’re integrally and directly related to the executive’s duties. Pay attention to travel that includes entertainment or personal components. Travel involving the executive’s family and friends is highly likely to require disclosure.

Requiring complete documentation. Several SEC enforcement cases involved allegedly incomplete, vague, and inconsistent documentation of expenses, such as documentation accompanied with general assertions that an expense was business-related.

Not relying only on executive self-disclosure. Questionnaires and certifications are useful for ensuring perk disclosures are complete and accurate, but companies should consider requiring other documents such as third-party receipts, credit card statements, itineraries, and company aircraft logs.

Training executives and disclosure personnel. Recurring training on executive perk rules can reduce accidental omissions and reinforce the importance of these disclosures. Ideally, training should include examples of disclosable perks identified in SEC enforcement actions.

This article does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg Industry Group, Inc., the publisher of Bloomberg Law and Bloomberg Tax, or its owners.

Author Information

David Peavler is partner at Jones Day and previously was regional director and associate director for enforcement at the SEC.

Evan Singer is partner at Jones Day and has defended corporations and their directors and officers.

These are personal views or opinions of the author; they do not necessarily reflect views or opinions of Jones Day.

Write for Us: Author Guidelines

To contact the editors responsible for this story:

Learn more about Bloomberg Tax or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

From research to software to news, find what you need to stay ahead.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.