Losses on intercompany loans due to exchange rate fluctuations should be deductible if the loan margin between the the lender’s and borrower’s countries are reasonable and based on market evidence of credit ratings, says economist J. Harold McClure.

In the recent AB GmbH case, the Tax Court of Münster correctly ruled in favor of a German multinational with respect to an intercompany loan to its Swiss affiliate (decision 10 K 764/22 (Feb. 20, 2025)) in a dispute over disallowed deductions for exchange rate losses within the framework of the Corporation Tax Act. The German parent, as the related party lender, experienced a modest unexpected exchange rate loss, and the tax authorities’ attempt to rewrite the terms of the intercompany contract was properly rejected.

The German tax authorities’ main concern appears to be that the exchange rate losses during the term of the intercompany loans were higher than the modest interest income from these loans. A research associate at the University of Passau discussing this decision noted that the tax authorities also objected to the nature of the intercompany loan due to the currency exchange rate risk and because one of the two intercompany loans was not collateralized. Alexander Peter, Unsecured Group Loan Was Arm’s Length, German Court Says, Tax Notes Int’l (Apr. 21, 2025).

During periods of low interest rates, overall losses from unexpected exchange rate losses may be consistent with arm’s length pricing. The economic issue should have been framed in terms of whether the 1.5% loan margin was appropriate. As we shall note, the representatives of the multinational had market evidence that the loan margin was indeed appropriate based on the borrower’s credit rating.

Negative Government Bond Yields in Europe

Interest rates on European government bonds dramatically declined during the Great Recession and continued to decline for several years. Blackrock’s Russ Koesterich noted the following:

“The last year has seen a proliferation of bonds trading with a negative yield, mainly in Europe. In effect, creditors are having to pay in order to lend money, and this has a number of implications for investors. Currently, 25% of the European sovereign bond market is trading with a negative nominal yield. In France, government bonds of up to 3 years carry a negative yield; in Germany, bonds up to 8 years do; and in Switzerland, bonds up to 10 years. Even more striking, there are examples of corporate bonds with a negative yield. For instance, back in February, yields on the bonds of Nestle (NSRGY) turned negative. The graph above shows the yield on the 10-year government bonds in Germany, Switzerland, and France. The yields currently stand at 0.2%, -0.1%, and 0.5%, respectively. In fact, the yield on the 10-year Switzerland bond went as low as -0.322% on February 3, 2015. As the graph suggests, the yields on these bonds have been on a downward trajectory since 2010. This is because the Eurozone has been grappling with deflationary pressures since the financial crisis. This has led to investors fleeing to safety by buying bonds. The German Bunds, in particular, are considered safe…Investment-grade corporate bond yields in Europe have also seen a similar cut. As mentioned above, the yield on the bonds of Nestle turned negative for a while. This is uncharted territory for corporate bonds. The yields issued by pharmaceutical company Roche (RHHBY) also flirted with the minus sign in February.”

Why Yields in Europe Turned Negative—Less Than Zero: The Implications of Negative Interest Rates, yahoo!finance (Apr. 14, 2025).

The fact that European government bond yields turned negative created a flurry of transfer pricing discussions that pondered the implications for intercompany loans. We should note that the arm’s length interest rate for corporate debt includes a credit spread so the arm’s length interest rate could be positive even if the corresponding government bond rate were negative.

Consider a simple example where a Swiss based multinational extended a 10-year intercompany loan in 2016 to its European affiliates where the loan was denominated in Swiss francs. While the Swiss long-term government bond rate was -0.5% at the time, a 0.75% credit spread would be warranted if the credit rating for the borrowing affiliates were A+. As such, the arm’s length interest rate would be 0.25%.

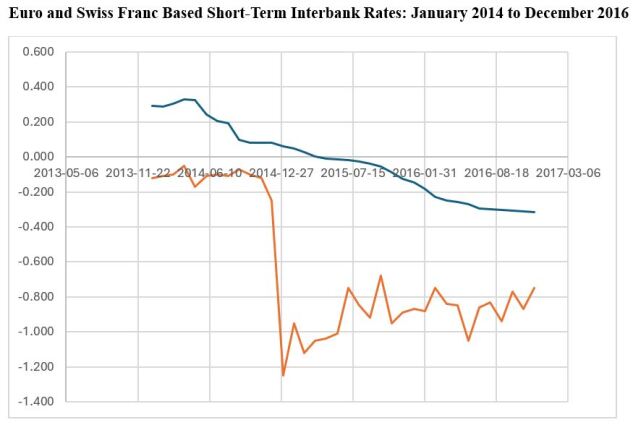

The Swiss affiliate in this litigation had both third-party loans and intercompany loans, which were very short-term. The following graph shows monthly observations from January 2014 to December 2016 for both the 3-month LIBOR rate for Swiss francs and the 3-month German interbank rate. The German rates were Euro-based and were approximately 0.3% in early 2014 and declined over time to around negative 0.3% by late 2016. The Swiss rates were slightly negative in 2014 but dropped to approximately -1% after the 2015 Swiss franc shock.

Exchange Rate Issues and the Swiss Franc Shock

The eurozone is a currency union of 20 nations that have adopted the euro as their currency. The 20 eurozone members are: Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Spain. While Switzerland did not join the eurozone, it did peg the Swiss franc to the euro from September 2011 to January 2015. The Swiss franc shock was mostly an unexpected appreciation of the Swiss currency. Raphael Auer, Ariel Burstein, and Sarah Leind describe the 2015 Swiss franc shock:

“On 15 January 2015, the Swiss National Bank (SNB) unexpectedly abandoned its minimum exchange rate policy of 1.20 CHF per euro. Initially established in September 2011 to shield Switzerland’s economy from safe-haven capital inflows during the euro area crisis, the policy helped contain excessive franc appreciation for more than three years. Removing the currency floor triggered a sudden and sharp rise in the Swiss franc—by around 15% against the euro—sending shockwaves through financial markets and exposing exporters and retailers to immediate price and competitive pressures.”

Ten years after the Swiss franc shock: Lessons on prices, expenditure switching, and inequality, VoxEU.org (Jan. 28, 2025).

While the Swiss franc purchased 0.83 euros during the fixed exchange rate period, the exchange rate appreciation had the Swiss franc worth 0.96 euros from early 2015 through the summer of of that year. The value of the Swiss franc temporarily dropped to 0.92 by the middle of 2016, but then by early 2025 was worth 1.07 euros.

Financial economic theory postulates that there is a relationship between interest rates and foreign exchange rates of one country compared to another country. The Interest Rate Parity proposition holds that the expected change in the exchange rate between two country’s currencies is equal to the percentage difference between the risk-free nominal interest rate between the two countries.

Overview of AB GmbH Case

In AB GmbH, the interest rate on German government bonds equaled 0.25% in June 2014 (the date of one of the third-party loans), while the interest rate on Swiss government bonds was -0.1%. This 0.26% difference would be the compensation for the expected devaluation of the euro with respect to the Swiss franc.

But the unexpected appreciation of the Swiss franc during the shock in 2015 caused unexpected gains for any German lender to this Swiss affiliate.

During June 2015, the interest rate on short-term German financial instruments was barely negative while the interest rate on Swiss financial instruments was around -1%. The interest rate differential suggested a modest expected appreciation of the Swiss franc. But from June 2015 to June 2016, the modest devaluation of the Swiss franc was likely not expected. As such, the German parent as the related party lender experienced a modest unexpected exchange rate loss. While the German tax authorities tried to deny this deduction, the Tax Court rightfully rejected the tax authorities’s attempt to rewrite the terms of the intercompany contract.

The Details of the Loans Taken by the Swiss Borrower

The intercompany loans were made in June 2015 and August 2015 with both being denominated in Swiss francs with interest rates following the Swiss franc LIBOR rate plus a 1.5% loan margin. The pricing issue was whether this 1.5% loan margin was adequate compensation for the German parent as a lender given the credit rating of the Swiss borrowing affiliate.

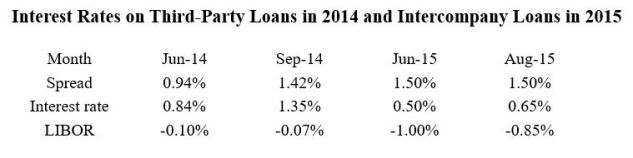

The Swiss affiliate had taken out two third-party loans with one being in June 2014 and the other in September 2014. The 2015 intercompany loans were unsecured and taken to retire these two third-party loans. All loans were short-term and denominated in Swiss francs. The following table summarizes the pricing terms for both third-party loans and both intercompany loans.

The third-party loans were fixed interest rates loans. Our table calculates the implied spread as the difference between the fixed interest rate and the Swiss 3-month LIBOR rate. This spread was only 0.84 % for the June 2014 loan but was 1.42% for the September 2014. The difference in these estimated spreads was due in part because the June 2014 was secured by a guarantee from the German parent, while the other third-party loan was not.

The Tax Court decision notes:

“A C AG had existed under its first name as J AG since 197x [mid-70s] and had therefore existed for almost 40 years at the time the loans were granted. The company still exists today … Nevertheless, it – the plaintiff – had conducted an external price comparison using the methodology of a creditworthiness analysis using rating tools and subsequent comparison with comparative bonds.”

In other words, the Swiss affiliate had been a third-party earlier in 2014 and before the 2015 intercompany loan was initiated. The third-party loans in 2014 could be used as a means for evaluating whether the 1.5% loan margin was appropriate, which we shall evaluate after discussing this “external price comparison” prepared by the representatives of the taxpayer. The Tax Court decision notes how the representatives of the taxpayer used Moody’s RiskCalc to determine a credit rating of Baa2 (equivalent to a S&P rating of BBB) although suggestions that the credit rating should be as low as Ba2 (S&P BB) existed. A credit rating of Baa2 would be consistent with loan margins near 1.5%, while a lower credit rating would suggest a higher loan margin.

The Tax Court’s references to the taxpayer’s evidence states:

“The creditworthiness analysis submitted had proven that companies with identical creditworthiness to A C AG had refinanced themselves unsecured on the capital market in Swiss francs at interest rates of between 0.63% and 1.75% … The interest rate of CHF LIBOR + 1.5% chosen by the plaintiff was therefore at the upper end or even above the comparative loans and correspondingly included a premium compared to a secured bond. An internal comparison with bank loans received in the A group also showed that the margin chosen by it was 1.5%, at the upper end of comparable external financing.”

There appears to be some confusion with respect to the range of loans margins versus the range of interest rates. We noted earlier that the Swiss LIBOR rate was negative so the effective interest rate was lower than the 1.5% loan margin. If this 0.63% to 1.75% range represents market loan margins, then the taxpayer’s evidence supports the arm’s length nature of the intercompany loans.

The third-party evidence indicates that the appropriate margin for an unsecured loan was near 1.5%, while the margin for a secured loan was near 1%. In other words, the value of the guarantee was approximately 0.5%. While the German tax authorities attempted to question the nature of the intercompany loans not being secured, this evidence supported the proposition that a 1.5% loan margin was sufficient compensation for the lack of a guarantee.

The Case Continues to Be Litigated

The German tax authorities have appealed this case to the Bundesfinanzhof-Germany’s highest tax court. Our review of this case has suggested that the pricing issue relates to whether the 1.5% loan margin was reasonable. If the appropriate credit rating for the Swiss affiliate were Baa2 rather than Ba2, the market evidence supports the taxpayer’s position.

This article does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg Industry Group, Inc., the publisher of Bloomberg Law and Bloomberg Tax, or its owners.

Author Information

J. Harold McClure, Ph.D., is an economist who has worked in transfer pricing for over 25 years.

Author Guidelines: Write for us.

Learn more about Bloomberg Tax or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

From research to software to news, find what you need to stay ahead.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.