Due to recent international tariff increases, multinational enterprises are reassessing the resilience of their transfer pricing models and exploring options to mitigate impact, say Loyens & Loeff practitioners.

Tariffs are by no means a new phenomenon, but recent developments have had a profound impact on global supply chains and international trade. From the US tariff waves introduced under the Trump administration to the retaliatory measures imposed by key trading partners, including the European Union, protectionist policies have re-emerged as a defining feature of the international trade landscape. In this increasingly complex environment—marked by both direct and indirect tax pressures—it is essential for multinational enterprises (MNEs) to reassess the resilience of their transfer pricing (TP) models. This article explores how rising tariffs can disrupt existing TP arrangements and highlights observed approaches companies take to manage their financial and operational impact.

Impact of Sudden Tariff Increases

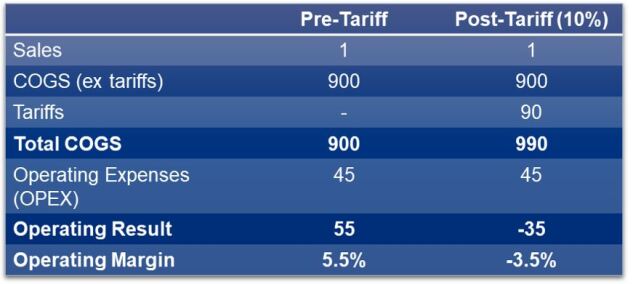

Tariff increases, typically recorded as part of the cost of goods sold (COGS), inject an immediate cost shock into the supply chain. For MNEs, this can significantly reduce the profitability of the importing entity if pre-tariff prices are not adjusted. A 10% tariff, for example, can easily wipe out a distributor’s 5.5% margin, pushing it into a loss position, as illustrated below.

In the short term, MNEs may have limited room to maneuver. While longer-term mitigation strategies exist (see further), many businesses initially adopt a “wait-and-see” approach given the current volatility of global trade policies. Still, immediate questions arise as to how the tariff cost should be reflected in intercompany pricing.

If the tariff cost cannot be passed on to the customer, the key TP question becomes: who in the group should bear the cost? This depends on intercompany agreements, the functional and risk profile of the parties involved, and the realistic alternatives available to each. In principle, the importer bears the tariff burden unless a different allocation is contractually supported and economically justified. The additional cost must be factored into the transfer price in a way that aligns with both TP and customs valuation principles.

Managing the TP impact of tariffs within the existing supply chain setup is critical to mitigate double taxation risk and ensure a defensible, consistent profit allocation in the face of external shocks.

Passing on Tariffs to the Customer

Although tariffs are legally borne by the importer, they are often passed on—fully or partially—to end customers. This is more feasible in markets with limited competition, niche positioning, or strong pricing power—where customers have little ability to switch or negotiate pricing (e.g., patented pharmaceuticals or high-end semiconductors).

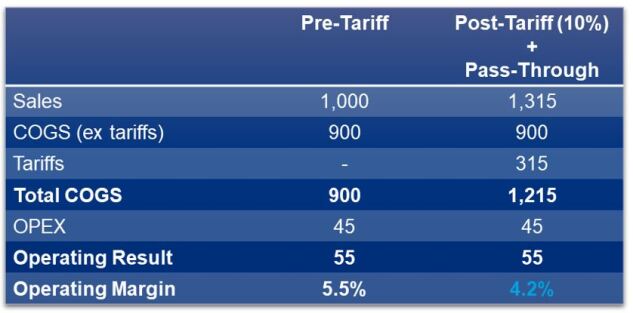

Even in cases of full pass-through, the TP impact should not be overlooked. While absolute profit may remain unchanged in such scenario, the operating margin as a percentage of sales declines, since both revenue and costs increase, as illustrated below.

In such cases, rising tariffs may cause margins to fall outside the interquartile range established in the TP analysis (e.g., for a limited risk distributor (LRD) remunerated based on the transactional net margin method (TNMM)). When that happens, the TP question becomes whether an upward adjustment is required. This depends on whether comparable third-party distributors would have been able to maintain their pre-tariff margins under similar tariff pressure. As real post-tariff financial data is rarely available during the fiscal year, companies should support their position using the existing contractual and functional analysis, supplemented with industry and macroeconomic data showing broader margin compression trends—both for the group and across the market—under current and prior economic shocks.

Passing on Tariffs to the Foreign Principal—LRD Perspective

In practice, many multinational groups are unable—or choose not—to pass increased tariff costs on to end customers, particularly in highly competitive markets with limited pricing flexibility (e.g., when competitors are not subject to similar tariff levels, or where preserving brand value takes priority). In such cases, the tariff effectively becomes an internal cost within the group, raising a fundamental TP question: who should bear it?

A common scenario involves a local LRD that purchases goods from a foreign principal and earns a stable, routine return based on its limited functions and risks. Where the LRD has no control over sourcing, pricing, or customs classification, allocating the full cost of tariffs to that entity may be difficult to defend—particularly if it would push its margin below the arm’s length range. A downward adjustment to the transfer price may be warranted to preserve the LRD’s target margin, especially where the foreign principal retains control over key decisions, bears market and pricing risks, and has a strategic interest in maintaining access to the local market. While the arm’s length principle does not prohibit allocating losses to low-risk entities, such an outcome must align with the actual control of relevant risks and the behavior of independent parties in comparable circumstances.

Let’s now turn to what this looks like in practice.

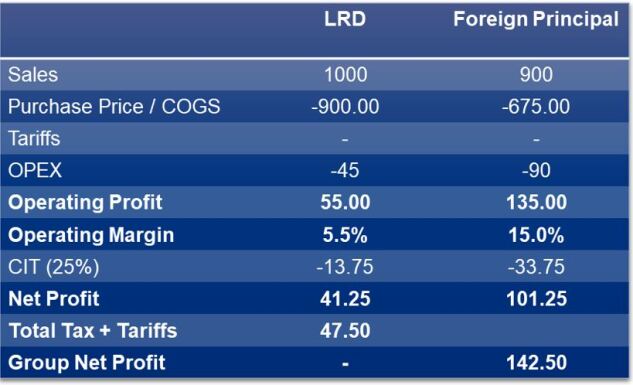

In the simplified example below, we begin with a baseline scenario where an LRD purchases goods from a foreign principal with a target operating margin of 5.5%.

We then compare two outcomes following the imposition of a 10% tariff:

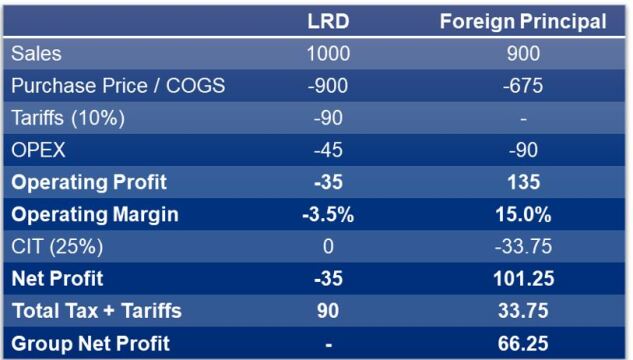

Scenario 1—LRD Absorbs the Tariff

The LRD bears the full 10% tariff, reducing its operating margin to –3.5%. This outcome may raise concerns if the comparability analysis indicates that a routine distributor in this fact pattern would not be expected to absorb such extraordinary costs.

Scenario 2—Tariff Passed on to the Principal

In this alternative, the foreign principal reduces the transfer price to offset the tariff impact. This allows the LRD to maintain a 5.5% margin, provided that the resulting margin remains consistent with the revised arm’s length range post-tariff, which may itself reflect broader margin compression observed in comparable independent parties.

Beyond preserving the LRD’s profitability, this adjustment has a second benefit: by lowering the transfer price, the customs value also decreases—thereby reducing the absolute amount of tariff payable. As a result, the combined tax and tariff burden for the group drops from 123.75 in Scenario 1 to 108.86 in Scenario 2.

This demonstrates how a TP adjustment aligned with the economic substance of the transaction may simultaneously improve customs efficiency by lowering the dutiable base.

Sharing the Burden—When Cost Allocation Becomes Justifiable

It is not a given that the foreign principal should always absorb the full tariff cost. As in all TP matters, the appropriate outcome depends on the specific facts and circumstances.

In cases where tariffs are substantial, the group may face a consolidated loss—potentially even below the principal’s production cost. In such scenarios, it may no longer be commercially realistic to assume that the principal would continue supplying the LRD under unchanged terms. Based on its own marginal cost and revenue curves, the principal may no longer find it economically viable to produce and supply the same volumes at reduced profitability. In parallel, the principal might consider redirecting supply to untariffed markets, if such options exist. Meanwhile, the LRD—especially if economically dependent and lacking alternative suppliers—may have a strong interest in preserving market share.

Under these conditions, sharing the tariff burden between principal and LRD may be aligned with the arm’s length principle, provided the facts support it. The OECD’s Options Realistically Available (ORA) framework is particularly relevant: if the LRD’s best realistic option is to remain in the market on revised terms rather than lose access to the product, a temporary margin reduction may be defensible.

Importantly, in most cases there is no single arm’s length price, but rather a range of acceptable outcomes. Where supported by the functional and economic analysis, it may be appropriate to operate at the lower end of the range—or even temporarily below it in exceptional circumstances—to reflect plausible behavior between unrelated parties facing similar external shocks.

Further, the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines 2022 (OECD TP Guidelines) recognize that temporary deviations from standard returns may be justified in exceptional circumstances. The fact that a LRD does not bear entrepreneurial market risk does not imply that it must be shielded from all adverse outcomes. This is particularly relevant where sudden and substantial tariffs disrupt the normal cost structure in ways that fall outside the ordinary risk assumptions. Support can be found in the following OECD TP Guidelines sections:

- §6.184 allows for the renegotiation of pricing arrangements where unforeseen developments fundamentally alter the economic assumptions underlying the transaction;

- §1.153 (on price control regimes) emphasizes that independent enterprises are not expected to operate on a no-profit basis, and asks whether third parties would have shared losses under comparable pressure;

- The OECD COVID-19 Transfer Pricing Guidance (§2.2) acknowledges that even routine entities may earn lower profits or incur losses when extraordinary events affect their profitability.

In all cases, the key is to support the outcome with sound economic reasoning, functional analysis, and clear documentation of the commercial logic behind the revised allocation.

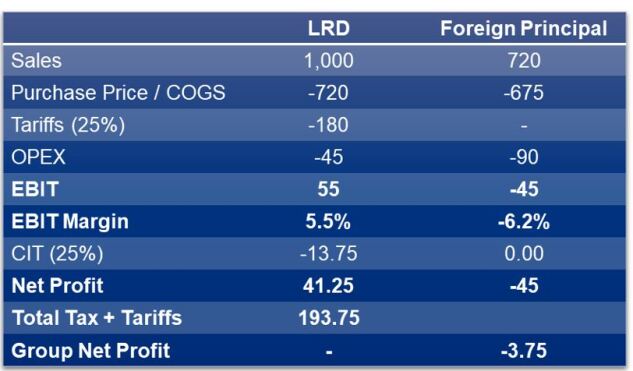

The impact of burden-sharing can be illustrated through the following example, based on a sudden tariff increase of 25% applied to the above baseline scenario. We distinguish two scenarios:

Scenario 1 – Principal Bears Full Tariff Cost

The LRD maintains its full 5.5% operating margin, but the principal absorbs the entire tariff cost, resulting in a negative EBIT margin of –6.2%. At group level, this leads to a consolidated net loss of –3.75 after tariffs and taxes.

Scenario 2—Tariff Cost Shared

Here, the LRD’s margin is reduced to 1%, corresponding to the lower end of the benchmarked range. The principal still records a small loss, but the LRD stays profitable, and the group’s net loss narrows to –1.5—mainly due to a lower tax burden in the LRD’s jurisdiction.

Provided this outcome is supported by a robust functional and comparability analysis, partial cost sharing may lead to a more balanced and defensible result under the arm’s length principle.

In conclusion, there is no one-size-fits-all answer. Any departure from standard TP policies should be carefully substantiated and documented to withstand scrutiny by tax authorities.

Observed Responses to Manage the TP Impact of Tariffs

As illustrated, tariffs can materially affect both the import cost of goods and the functioning of existing TP models. In practice, we observe that many MNEs are adopting a cautious stance, given the rapidly evolving trade environment and the possibility of new trade agreements, while at the same time exploring potential strategies to manage the impact.

These responses can be grouped into short-term, mid-term, and long-term measures, depending on the degree of structural change required. This distinction is important, as the unpredictable and often temporary nature of tariffs can complicate both the feasibility and desirability of more far-reaching adjustments. The appropriate response will depend on the nature of the goods involved, the magnitude of the tariffs, and the operational flexibility within the group.

Short-Term Considerations

These short-term considerations can generally be implemented in a relatively straightforward manner without affecting the applicable TP model and flow of goods. Generally, no structural changes are needed, and these alternatives are mainly aimed at refining the applied TP, inventory, and supply chain.

Inventory Optimization and Supply Chain Review

Accelerating imports ahead of tariff implementation dates can be a practical—albeit temporary—mitigation strategy. This requires close monitoring of tariff implementation timing and ensuring adequate warehousing capacity for early shipments.

A more structural response involves reviewing the geographic setup of production and distribution. MNEs may consider shifting to more localized manufacturing or sourcing inputs either domestically or from countries not subject to tariffs, thereby reducing exposure to cross-border duties. However, such changes can affect the functional profile and risk allocation of group entities, potentially triggering TP consequences such as the need for a business restructuring analysis or adjustments to existing TP policies. Any operational realignment should therefore be carefully assessed from a TP perspective.

Review and Validation of Existing TP Arrangements

MNEs can assess whether their current TP policies remain compliant with applicable regulations and are correctly implemented in practice. This includes verifying the accuracy of intercompany pricing mechanisms, customs valuation methods, and the underlying documentation. Some transactions may have gained renewed relevance in light of recent tariff developments and should be re-evaluated accordingly.

Particular attention should be paid to the intercompany transaction value that serves as the basis for customs valuation, rather than solely focusing on achieving an arm’s length profit outcome for corporate income tax purposes. In this context, MNEs operating in the US may assess whether they can apply the First Sale Rule to reduce the customs value. While potentially effective, the application of this rule in intercompany settings is subject to strict conditions and heightened scrutiny by the authorities, and should therefore be approached with caution.

It is also advisable to analyze bundled transactions involving goods, services, intellectual property (IP), and logistics to determine whether a separate TP analysis is warranted for each component. In a no-tariff environment, bundling may have been operationally convenient from a TP perspective. However, in the current tariff context, unbundling these elements may provide more accurate support for the allocation of intercompany charges. That said, separately pricing these components may not reduce the customs value of imported goods, as related payments may still need to be included under specific customs rules.

Finally, a review of the customs valuation of imported goods should be carried out in parallel to ensure alignment with the underlying TP framework. Where TP policies or supply chain structures have changed, customs valuation methods may need to be adjusted accordingly to remain compliant with both TP and customs regulations.

Mid-Term Considerations

Whereas short-term considerations generally do not affect the overall TP model, we observe that some companies are, in the medium term, exploring adjustments to their existing TP arrangements that do not involve changes to the physical movement of goods. These adjustments aim to better align with evolving economic conditions or shifts in business strategy, while remaining consistent with the arm’s length principle.

Reallocation of Risks

In response to a less globalized and more fragmented trade environment, some MNEs are re-evaluating their global supply chains and business models. This trend often involves greater decentralization and increased local responsibility for decision-making. As a result, certain groups are also reconsidering how risks are allocated across their group, particularly where operational responsibilities or market exposure have shifted. Such reallocation of risks can, in turn, affect transfer prices and the customs valuation of goods.

In these cases, both contractual and functional risk allocation may be revisited. While intercompany agreements may be updated to reflect a new allocation of risks, such contractual terms must remain consistent with the actual conduct of the parties. Given the growing focus by tax authorities on substance over form, any changes in risk allocation must be aligned with the group’s operational reality.

IP Transfers

Building on the above, some MNEs consider even more structural changes to their business model, such as the internal transfer of IP. These transfers can take various forms—from the reallocation of regional marketing intangibles or distribution rights to the reallocation of more valuable group IP. Such changes may reduce the customs value of imported goods and thereby mitigate the impact of tariffs, particularly where they result in lower transfer prices charged by the exporting entity.

However, intra-group IP transfers can trigger direct tax consequences, notably capital gains taxes in the jurisdiction of the transferring entity. Moreover, given the structural nature of such changes, companies should account for the potential future use of such IP before implementation. Where the transferred IP continues to be used across multiple jurisdictions, MNEs should also consider the resulting royalty flows and related withholding tax implications when evaluating such alternatives.

Long-Term Considerations

The evolving geopolitical, economic, and regulatory landscape pushes MNEs to re-assess the structure and distribution of key business functions. In case the current tariff environment becomes more permanent, considering these elements would become more relevant. Key considerations to explore include:

- Localizing production and operations: More manufacturing, R&D, or service functions may be relocated closer to end markets to enhance resilience and reduce dependency on global supply chains. This may require changing the overall business, supply chain and TP model of an MNE, so is probably not a step that MNEs will take lightly. However, in case of establishing new production locations, the current tariff situation should be considered to determine the preferred set-up.

- Market presence: In light of rising operational costs—including tariffs—some MNEs are reassessing their presence across markets. This often involves a strategic review of whether continued operations in certain jurisdictions remain economically justified. Factors considered include market growth potential, profitability, regulatory and tax environments, and alignment with long-term business objectives. Such reviews can inform decisions on market exit or further expansion and are increasingly relevant when evaluating whether to maintain or establish a presence in high-cost jurisdictions.

- Evaluate centralized models: Principal structures, LRDs, and centralized procurement hubs are commonly used by MNEs. These models offer operational synergies and can also provide tax efficiency. However, in the current environment there may be potential benefits of decentralization in terms of agility, market responsiveness, and regulatory alignment. Therefore, especially when thinking about expansion of such arrangements, MNEs may take this into account and consider whether a decentralized approach may be more favorable in the current environment and towards the future.

Any significant restructuring – such as the relocation of functions, assets, or risks—should be carefully planned to mitigate potential exit tax exposures and TP consequences. Also, given the structural nature of such changes, MNEs must ensure that any restructuring aligns with their long-term business strategy and operational objectives.

This article does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg Industry Group, Inc., the publisher of Bloomberg Law, Bloomberg Tax, and Bloomberg Government, or its owners.

Author Information

Aldo Engels, attorney at law, is a member of the Direct Tax Group and heading the Transfer Pricing Team in Belgium of Loyens & Loeff. Jan-Willem Kunen, tax adviser, is part of the Transfer Pricing Team of Loyens & Loeff in the Netherlands and specializes in advising internationally operating clients on Dutch and international transfer pricing matters.

Write for Us: Author Guidelines

Learn more about Bloomberg Tax or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

From research to software to news, find what you need to stay ahead.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.