KPMG practitioners analyze how the imposition of tariffs may affect multinationals pricing their intercompany transactions and the additional risk of tax authority disputes.

The imposition of unexpectedly high and universal tariffs on imports of goods by the US, and uncertainty surrounding whether and when these new tariff rates will be re-negotiated, has created significant disruption to multinationals’ product pricing and supply chains. This will have a resultant impact on multinationals’ profitability, at least in the near- to short-term until they are able to understand and take action to adapt to the new economic realities. This article explores consequences for how multinationals price and support their intercompany transactions during this period of unrest in the near- to short-term, and the additional risk of tax authority disputes.

I. Imposition of High and Uncertain Tariffs

Over the last half century, tariff rates on goods across the globe have declined substantially driven by the desire to increase global trade and promote economic growth. Many trace the decline in tariff rates to the 1947 General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which was later replaced in 1995 by the World Trade Organization (WTO), and supplemented by numerous other bilateral and multilateral trade agreements such as the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). Even countries such as India, which in 1990 was largely a closed economy with an official import substitution policy and weighted average tariffs exceeding 50%, has since reduced its weighted average tariff rate to mid-single digits.

While many countries have continued to maintain tariffs to varying degrees in order to protect or promote certain domestic industries, or as an additional source of tax revenue, the overall global trend has been that of declining tariff rates and increasing cross-border trade. That is, until recently.

On April 2, 2025, the Trump administration announced across the board ad valorem tariffs on imports of goods from almost every country—ranging from 10% to 50+%. The announced tariffs were a baseline tariff of 10% plus additional reciprocal tariffs for some 60 countries and trading blocs. Canada and Mexico were not included in the April 2 tariff announcement as the US recently instituted tariffs of up to 25% on Canada and Mexico, except for USMCA compliant goods. In addition, China was levied a baseline and reciprocal tariff of 34% in addition to the 20% tariff imposed earlier this year.

This was a sudden and dramatic increase compared to the US weighted average tariff rate of only about 2% in recent years. Some countries, such as Vietnam and Israel, have declined to introduce reciprocal tariffs or reduced their tariffs on US imports in response to the imposition of US tariffs.Other countries have responded in kind, such as the world’s largest exporter, China, which announced a 34% across-the-board tariff on its imports from the US starting April 10, 2025. Highlighting the uncertainty in this area, the reciprocal component of the US announced tariffs were subsequently paused for 90 days, with the exception of China.

With global trade in 2024 of about USD 33 trillion, of which 60% to 80% is estimated to come from intercompany transactions driven by globalization and extended supply chains, the sudden imposition of high tariffs by the US, and possible retaliatory actions by other nations, has the potential to create significant business disruption and significantly impact business profitability in the short term. Compounding this is the uncertainty of whether and when the new US tariff rates may be re-negotiated, at least for some countries, which makes it challenging for businesses to develop longer term strategic responses. As of the time of this article, there is considerable uncertainty as to whether the US will negotiate on the tariffs announced on April 2, or the extent other countries will impose retaliatory tariffs. For example, public reports suggest that the US government may view announced tariff rates as the starting point for negotiation, and the administration has reported that more than 75 countries have expressed interest in negotiating trade deals.

II. Shorter-Term Versus Longer-Term Implications

Tariffs are taxes that are a cost to corporations and consumers alike. Tariffs are technically levied on the importer of record, but importers generally attempt to pass on some or all of their increased costs to consumers in the form of higher prices. Thus, the economic impact of tariffs are potentially borne by both suppliers and consumers. In the longer run, both can be expected to take action to adapt to the added costs of tariffs. Corporations reassess where they manufacture or source products, and whether to continue to supply certain markets, in order to achieve an acceptable level of profitability. Consumers reassess their consumption patterns often based on price sensitivity and evaluate potential substitute products.

In the short run, many businesses will face challenges in revamping their historic supply chains to avoid the newly imposed US tariffs. They may need to find and qualify comparable suppliers domestically, assuming such suppliers exist currently. They may not be able to onshore manufacturing without further investment in manufacturing facilities unless there is sufficient excess domestic capacity. In some cases, it may be several years before businesses are able to make the investments to shift manufacturing or find alternative suppliers, assuming they are able to even do so.

Furthermore, businesses may be reluctant to take actions with longer term ramifications while they are still absorbing and evaluating implications of the new tariff regime, especially when there is significant uncertainty as to whether the new announced tariff regime will prevail as is, and how durable it may be.

Instead, in the immediate aftermath of the new US tariffs we see corporations making temporary decisions based on imperfect information in an effort to minimize costs and/or protect sales. For example, in response to the new US tariffs, some companies temporarily halted imports or reduced plant production overseas to reduce tariff costs, which will result in lost sales. Others took action to protect sales, e.g., by expediting shipments to the US and bulking up inventory prior to the new US tariffs taking effect, potentially incurring higher shipping and inventory costs.

For multinationals, the decisions they make in the near- to short-term can have a material impact on their profitability and, consequently, their transfer pricing policies. In particular, from a transfer pricing perspective, it is important to consider who should bear the economic cost of any profit reductions arising from tariffs, or the cost of other decisions such as reducing import volumes into the US made in response to the new tariffs. As noted earlier, while the importer of record is responsible for paying the tariff to the taxing authority in the first place, it is widely acknowledged that some or all of the tariff cost is ultimately passed onto customers. There are also economic costs to the business from the imposition of tariffs such as lower volumes or not being able to pass along 100% of the tariff to customers. The transfer pricing question is whether, and how, this economic cost to the business should be shared between the importer and the related party from which it purchases goods.

In the following sections, we first discuss the impact on corporate profitability of tariffs, and then considerations for multinationals in how they set and support their transfer pricing in the near to short term during the period when they are still assessing and reacting to significant new, and uncertain, tariffs. We also highlight some of the potential increased tax controversy risks.

III. Profit Impact of Tariffs

The imposition of tariffs is an added cost of doing business. If the corporation chooses not to pass along the tariff cost to customers in order to, say, protect longer term market share or avoid negative brand perception from price increases, its profits will decline in proportion to the increase in costs—at least in the near- to short-term till it can take longer-term action to address the cost increase. And if it does pass along all or a portion of the added costs, customers may choose not to buy or to buy less depending on alternatives available to them, their price sensitivity or urgency of the purchase, with a negative impact on corporate profits. The following stylized example illustrates the conundrum.

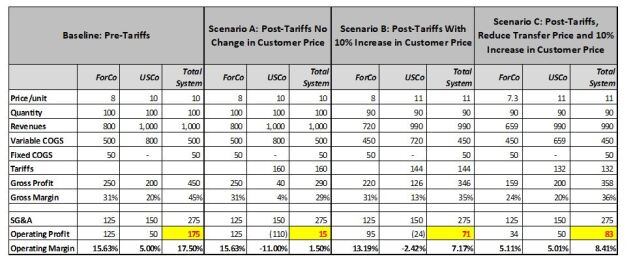

Assume a foreign entrepreneur (ForCo) manufactures and sells in the US though a related party US distributor (USCo). Pre-tariffs, USCo buys 100 units of product from ForCo for $8, which it subsequently sells to US customers for $10 a unit. Assuming variable manufacturing costs of $5 per unit and fixed manufacturing costs of $50, total system profits are $175, or an operating margin of 17.5%.

An ad valorem tariff of 20% is subsequently imposed on USCo’s import of products. Based on prior experience, the multinational believes that a 10% increase in price would reduce customer demand by 10%.

The multinational evaluates various scenarios such as:

1. Not changing the customer price and consequently units sold (Scenario A),

2. Increasing the customer price with a resultant decrease in units sold (Scenario B), and

3. Reducing the transfer price in order to minimize the impact of the tariff and increasing the customer price (Scenario C), assuming this can be done consistent with applicable customs and transfer pricing rules.

As shown in Table 1, the total system profit, i.e., the combined profit of ForCo and USCo, is lower in all post-tariff scenarios than in the baseline pre-tariff scenario. And if customer demand was more elastic, meaning customers were more sensitive to any price increase, the system profit in Scenarios B and C would be even lower than shown in Table 1.

Economists refer to the ratio of the percentage change in quantity demanded to the percentage change in price as the price elasticity of demand. Goods that with an elasticity >1 are called elastic, while goods with an elasticity < 1 are inelastic. If demand were perfectly inelastic, the business could pass along 100% of the tariff to the customer without any change in demand, and there would be no reduction in business profits from a tariff. But perfectly inelastic demand is rare. In addition, one might argue that if demand in our stylized example were somewhat inelastic, system profit would be reduced proportionately less than the increase in price, such that an increase in customer pricing post-tariffs would actually increase system profits. While mathematically that is true, this example does not consider real world implications such as increasing the marginal cost of production or brand damage from excessive pricing; otherwise, even in a pre-tariff world, system profits would be higher with higher customer pricing.

Table 1: Scenario Analysis—Profit Impact of Tariff Imposition

Regardless of the post-tariff scenario that the multinational chooses to follow initially, it is unlikely to be sustainable in the long run, as the corporation equity owners will seek potentially more lucrative investment opportunities elsewhere. In the long run, the multinational would seek to improve profitability by considering options such as exiting the tariffed market, changing manufacturing locations, finding cost savings to offset the tariffs, and so on. But to the extent these options to mitigate the tariffs are not feasible anytime soon, especially without significant additional investment, the multinational will have lower consolidated profits in the near to short term.

IV. Tariff Implications for Profit Allocation Amongst Related Parties

Regardless of whether one uses a one-sided method such as the Comparable Profits Method (CPM) or Comparable Uncontrolled Price (CUP) method, or a two-sided method like the Profit Split Method, transfer pricing is in many ways an exercise in how group (or system) profits are allocated among related entities at arm’s length. When there is an external shock, such as the imposition of significant new tariffs which lower the group’s consolidated profits, one would expect that parties acting at arm’s length would re-evaluate the allocation of profits.

At arm’s length, each party will consider its realistic alternatives in the face of the external shock, and its willingness to bear the economic cost of the system profit reduction arising from the tariffs.

One might argue that the economic cost of the system profit reduction should be borne by the group entrepreneur, or ForCo in our stylized example above, with the rationale that ForCo is the risk-taking entity in the group and USCo is simply a routine distributor. In some cases, this may be the most attractive option for ForCo – for example, if tariffs are expected to be short term and ForCo wishes to protect its market share, or if ForCo sees an opportunity to expand market share at the expense of competitors.

While having the entrepreneur bear the full economic cost of the system profit reduction may have merit and be arm’s length in some cases, one should not readily ignore other realistic alternatives available to the entrepreneur or the laws of demand and supply. It may be that the entrepreneur finds it more reasonable to bear only part of the tariff rather than the full cost, or to redirect its manufactured products to other markets without tariffs. Below we discuss using a stylized example.

In deciding how much to produce and at what price, a manufacturer will consider the market demand for its product and its production cost structure. Economic theory informs us that in a competitive environment, a manufacturer will maximize its profits when its marginal costs (i.e., the cost of producing one additional unit) equals its marginal revenue (i.e., revenue from that additional unit produced).

Production costs can be segregated into fixed costs and variable costs. Fixed costs are those that cannot be easily varied in the short term, such as investment in plant, property, and equipment. Variable costs are generally the raw materials used, labor costs, and other costs that vary with production levels. However, some would argue that labor costs are to some degree fixed in the immediate term as the business may not be able to adjust its labor force easily or without cost. At low levels of manufacturing, one would expect marginal costs to initially decline due to economies of scale (by spreading fixed costs over a higher production level), but to increase at some point, as economies of scale decrease and capacity limits are reached, such that the manufacturer has to pay overtime to increase production or lease added manufacturing space at high cost on a short-term basis. This is why the marginal cost curve is generally viewed as being U-shaped.

In the stylized example illustrated in Figure 1, pre-tariff the manufacturer’s marginal revenue and marginal cost are equal, and its profit maximization occurs, when it produces Q1 units which it is able to sell at $P1 per unit. For simplicity, assume a fixed tariff per unit is imposed. (For simplicity of discussion, we have assumed a fixed tariff amount per unit. Assuming an ad valorem tariff would lead to similar conclusions albeit with a more complicated discussion.) Further assume the manufacturer pays the tariff. Now, for every unit sold by the manufacturer, its marginal revenue or the price it receives for an additional unit sold, is reduced by the amount of the imposed tariff. That is, the manufacturer’s marginal revenue curve shifts down by this fixed tariff amount which is represented by the arrow AB in Figure 1.

After imposition of the tariffs, the new equilibrium where the manufacturer maximizes its profit is for it to produce Q2 units which it sells at a price of $P2. The difference between $P1 and $P2 represents the amount of the tariff ultimately borne by the manufacturer. This difference is smaller than the tariff amount represented by the arrow AB – illustrating that the manufacturer will ultimately only be willing to bear a portion of the tariff and will pass on the remaining tariff cost to the buyer of its products.

That is, the related party importer/distributor will be on the hook for bearing the balance of the tariff represented by the difference between the lines AB and P1P2 in Figure 1. Depending on the sensitivity to price increases of the customers to whom the importer sells, the importer will be able to pass on some or all of the tariff cost that it bears.

In conclusion, in the near- to short-term after imposition of the tariffs, before the business and consumers can fully adjust to the new economic realities, from an economic perspective one would expect that the ultimate burden of the tariff may be shared in some proportion among the entrepreneur manufacturer, its related party distributor, and the end customer. How this burden is shared will be a function on the market demand faced by the overall business, the business’ cost structure, and the sensitivity of the end customer to price increases.

Figure 1: Profit Maximization After Imposition of Tariffs

V. Implications of Tariffs for Historic Transfer Pricing Policies

It is quite common to apply the CPM as the best method to benchmark and test the arm’s length price at which a distribution entity imports and distributes products manufactured by a related foreign manufacturer. Specifically, the CPM, a one-sided method, is often used to benchmark the profit margin earned by the related party distributor compared to comparable uncontrolled distributors.

In a world of newly imposed and material tariffs leading to a decrease in the related party group’s profits, it may not be arm’s length to simply follow historic practices without adjustment. For example, the comparables may not all be similarly impacted by tariffs, and without involved further investigation and consideration, using these comparables may lead to an under- or over-estimation of the arm’s length profit margins the related party distributor should earn.

Furthermore, it is not uncommon for the comparables to be distributing products that differ both from each other and from those distributed by the related party distributor. To the extent the comparables’ and related party distributor’s customers have varying degrees of price sensitivity, their respective ability to pass the tariff cost to customers will differ, as will the profit implications.

Post-tariffs, it will be imperative for taxpayers to assess in detail how group profits have been impacted and how they should be allocated at arm’s length, given the incentives and opportunities available to each party. Referring back to the stylized example in Table 1, it may not be arm’s length for the manufacturer to bear the full burden of the tariff and reduce the transfer price in order to keep the related distributor’s margin at the historic 5%. Doing so is also likely to raise questions by ForCo’s taxing authority as to why the manufacturer alone is bearing all of the tariff cost.

It might be tempting post-tariff to simply adjust the transfer price slightly downwards such that the distributor’s margin continues to remain within the benchmarked arm’s length range. Even if this is possible—and it may not be, depending on the tariff’s impact on group profitability—the manufacturer will potentially suffer a disparate impact, leaving it at a disadvantage in a local tax examination. On the other hand, keeping the transfer price constant or even increasing it to protect the manufacturer’s margin, will adversely affect the distributor’s margin, and furthermore not help reduce the tariff paid. Lastly, it is not uncommon for tax authorities to focus not only on margins but also on the absolute amount of profit reported. And , when group profit overall is significantly reduced (as is the case in each of Scenarios A through C in Table 1 above) and there is less profit to allocate amongst the related parties, taxpayers may struggle to defend against examination scrutiny.

There will also need to be considerable attention paid to the financial data of the comparables that are used to benchmark the profitability of the related party distributor. It is common practice to use multiple years of data when applying the CPM in order to smooth out the impact of market and business cycles. However, this may not be appropriate when significant economic shocks, such as the new tariffs, are present. Further, the delay in reporting financial data for comparable companies may create challenges creating a benchmark range in which the financial results of both the comparables and the tested group company have been impacted by the tariffs. In addition, even if a comparable is impacted in the same way as the tested party in terms of tariffs, it may be important to thoughtfully realign the financial data in the case of different fiscal year ends.

In short, there is no simple answer as to how taxpayers should assess the implications of the tariff on group profits and how that profit should be allocated among related parties at arm’s length. Suggestions abound, from targeting the edge of the benchmarked range for the distributor or manufacturer, to allocating all tariff costs to the entrepreneur, to allocating the system profit reduction (or tariff cost) pro-rata based on the pre-tariff profit allocation, in the belief that the pre-tariff profit allocation suggests the relative value contribution of each related party.

Regardless of the approach selected, tax departments will need to have appropriate documentation and support for whatever position they take, based on the facts and how parties would negotiate at arm’s length and not simply on what is most expedient. It is clear that preparing this documentation and support is likely to be more involved than in pre-tariff years.

Compounding the pressure, one can expect on-going uncertainty as the underlying tariff landscape evolves as well as businesses assess the tariff implications, take actions to the extent possible to mitigate these implications, and re-evaluate customer pricing structures. As such, it is likely that tax departments will not be able to plan far in advance around their transfer pricing policies and will face a compressed timeline in understanding the impact of the tariffs on their transfer prices and preparing the appropriate documentation and support.

VI. Audits and APAs

The impact of tariffs on transfer pricing will inevitably lead to increased tax audit risk. On the one hand, foreign tax authorities are likely to bristle at reduced profits in their local manufacturers and entrepreneurs arising from US-imposed tariffs. Tax auditors, especially in jurisdictions antagonistic to US tariffs, may be inclined to view tariff costs as a US problem that should be borne solely by the US distributors.

On the other hand, inbound distribution margins have long been a focus of IRS scrutiny. The IRS ran an inbound distributor campaign in 2017, and renewed its focus in the area beginning in late 2023, with over 150 compliance alerts sent to US subsidiaries of foreign companies which the IRS believed, based on its analysis of their 2017-2021 tax returns, were reporting losses or inappropriately low profits in the US. While IRS staffing and enforcement priorities for the coming years remain unclear, it is reasonable to expect that inbound distribution will remain a focus, especially as the IRS’ 2023 efforts show that it has the ability to identify a broad swathe of companies reporting what it considers potentially unacceptable profits. While foreign tax authorities may wish to see US tariffs as a cost that should be borne by US companies, that view is unlikely to find any sympathy with the IRS, which is more likely to regard US tariffs as costs attributable to foreign entrepreneurs, where feasible.

To the extent US tariffs engender retaliatory tariffs in foreign jurisdictions, the above positions are likely to be reversed. Tax authorities considering the effects of tariffs on a case-by-case basis are apt to take inconsistent positions depending on what benefits them. Tariffs are therefore likely to result in double taxation and in the need for competent authority relief via the mutual agreement procedure (MAP) under applicable tax treaties, where it is likely that – given the historically very high rates of success in MAP – tax authorities will find a way to compromise and eliminate double tax.

For taxpayers with existing advance pricing agreements (APAs), tariffs raise a different set of considerations. Once signed, a US APA is binding for its term on both the IRS and the taxpayer, subject to the satisfaction of certain critical assumptions laid out in the APA. The standard critical assumption language posits that "[t]he business activities, functions performed, risks assumed, assets employed, and financial and tax accounting methods and classifications [and methods of estimation] of Taxpayer in relation to the Covered Transactions will remain materially the same as described or used in Taxpayer’s APA Request,” but that "[a] mere change in business results will not be a material change.”

Competent authorities have historically been loath to regard broadly applicable changes as triggering the failure of a critical assumption, and experience with both prior tariffs and the Covid-19 pandemic suggests that the imposition of tariffs would not trigger a critical assumption absent extraordinary circumstances. However, modifying supply chains in response to tariffs could cause a critical assumption to cease to be met, in which case the APA would need to be modified or, if modification by mutual consent proves impossible, canceled. Taxpayers with current APAs therefore have a more restricted set of options available for responding to tariffs, though an APA’s use of ranges may provide for some relief.

However, for many, APAs will provide an opportunity for certainty in an extremely uncertain time. Taxpayers seeking APAs are unlikely to meet with a one-size-fits-all solution to tariffs; how tariff costs are taken into account should depend on the nuances of the taxpayer’s value chain. Past experience suggests that, just as they managed to navigate the economic challenges of Covid-19 and other upheavals, APA programs will find ways to effectively respond to the impacts of tariffs.

This article does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg Industry Group, Inc., the publisher of Bloomberg Law and Bloomberg Tax, or its owners.

Author Information

Vinay Kapoor is a transfer pricing principal in the Economic & Valuation Services (EVS) practice in New York. Jack O’Meara and Jessie Coleman are principals, and Thomas Bettge is a senior manager, in the EVS group of KPMG LLP’s Washington National Tax practice.

The information in this article is not intended to be “written advice concerning one or more Federal tax matters” subject to the requirements of section 10.37(a)(2) of Treasury Department Circular 230. The information contained herein is of a general nature and based on authorities that are subject to change. Applicability of the information to specific situations should be determined through consultation with your tax adviser. This article represents the views of the author(s) only, and does not necessarily represent the views or professional advice of KPMG LLP.

Write for Us: Author Guidelines

Learn more about Bloomberg Tax or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

From research to software to news, find what you need to stay ahead.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.