On July 4, President Trump signed into law the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), a budget reconciliation bill with a broad range of provisions that impact both corporate and individual taxpayers. In addition to enacting several new provisions, the OBBBA makes permanent many provisions of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) that were otherwise set to expire.

Of particular note to US taxpayers with interests in foreign corporations, the OBBBA reinstates Internal Revenue Code (“IRC”) §958(b)(4), which limits downward attribution of stock ownership under the controlled foreign corporation (CFC) rules. The reinstatement of IRC §958(b)(4) eliminates what many perceive to be unintended consequences of its repeal by the TCJA. The OBBBA also adds new IRC §951B, which applies downward attribution principles in certain cases to more narrowly address the policy concerns that originally drove the repeal. As the implications of these changes are complex, we begin by illustrating how the downward attribution rules have previously applied, so as to better demonstrate their application going forward under IRC §951B.

Background and History of Downward Attribution Under the CFC Regime

A CFC is any non-US corporation that is more than 50% (by vote or value) owned by one or more “US Shareholders”. IRC §957(a). For this purpose, a “US Shareholder” is any US person (individual or entity) that owns 10% (by vote or value) or more of the foreign corporation. IRC §951(b). In determining whether a foreign corporation is a CFC and whether a US person is a US Shareholder thereof, ownership can be direct, indirect, or constructive.

Before the passage of the TCJA in 2017, the rules for determining constructive ownership under the CFC regime barred “downward attribution” of stock from a foreign person to a US person. Downward attribution occurs where stock is attributed “downward” from owners to corporations, partnerships, estates, or trusts in which they have an interest. The limitation in IRC §958(b)(4) thus effectively ensured that stock owned by a foreign shareholder could not be attributed to a US subsidiary.

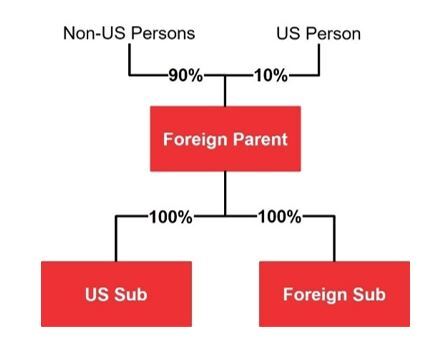

For example, prior to the TCJA, if a foreign parent company owned both a foreign subsidiary and a US subsidiary as brother-sister entities (as depicted in the diagram below), Foreign Parent’s interest in Foreign Sub would not be attributed to US Sub. As a result, neither Foreign Parent nor Foreign Sub constituted CFCs, as neither corporation was considered more than 50% owned by US Shareholders (directly, indirectly, or constructively). Moreover, neither the US Person nor US Sub were treated as US Shareholders of CFCs, and thus were not subject to the resulting anti-deferral rules (e.g., the Subpart F and GILTI regimes and CFC reporting requirements).

The TCJA repealed IRC §958(b)(4), thereby allowing downward attribution of stock from foreign persons to US persons under the CFC constructive ownership rules. Legislative history indicates that the repeal was intended to curb certain tax avoidance strategies, such as “de -control” transactions. These transactions often involve internal restructurings specifically implemented to prevent a foreign corporation that would otherwise be treated as a CFC from being so treated, thus allowing US taxpayers to avoid paying US tax on CFC income while still retaining underlying control.

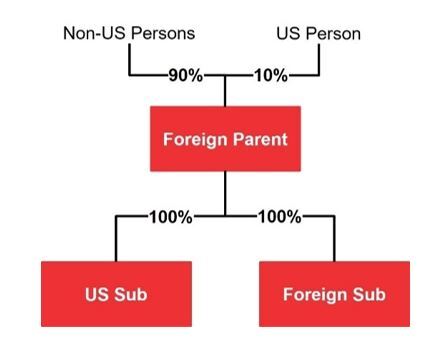

Notwithstanding its limited intent, the TCJA simply struck IRC §958(b)(4) from the IRC in its entirety, leading to significant (and presumably unintended) consequences. Specifically, repealing the prohibition on downward attribution caused many foreign corporations to suddenly be classified as CFCs solely due to the existence of US affiliates, even where US persons did not actually have control. Using the above example, Foreign Parent’s interest in Foreign Sub is downwardly attributed to US Sub, such that Foreign Sub is deemed owned by US Sub. As it is now considered 100% owned by a US person, Foreign Sub is classified as a CFC. Moreover, both US Person (the 10% shareholder of Foreign Parent) and US Sub are now treated as US Shareholders of a CFC, albeit with differing results.

The IRC has different rules for determining (i) whether a foreign corporation is a CFC and a US person is a US Shareholder, and (ii) whether such US Shareholder is subject to tax due to its CFC ownership. For determining whether a foreign corporation is a CFC and whether a US person is a US Shareholder thereof, the IRC looks to direct, indirect, and constructive ownership (including via downward attribution). IRC §957(a), §951(b). In contrast, the constructive ownership rules generally do not apply in determining whether a US person is subject to income inclusions under the Subpart F and GILTI regimes; only US Shareholders who own at least 10% of the CFC directly or indirectly may have a Subpart F or GILTI inclusions. IRC §951(a)(1), §951A(e)(2). In either case, US Shareholders of a CFC (including those with only constructive ownership) are generally subject to applicable reporting requirements, unless they qualify for relief under IRS guidance. See, e.g., Rev. Proc. 2019-40.

Returning to our earlier example (depicted again below), as US Sub only constructively holds shares in Foreign Sub (via downward attribution from Foreign Parent) but has no actual direct or indirect interest therein, US Sub is not itself subject to Subpart F or GILTI inclusions. However, US Person, the 10% shareholder of Foreign Parent, does indirectly own 10% of Foreign Sub; as a result, post-TCJA, US Person is indeed subject to Subpart F and GILTI inclusions with respect to Foreign Sub’s earnings, notwithstanding that US persons do not actually control more than 50% of this foreign entity.

The repeal of IRC §958(b)(4) has thus had far-reaching consequences well beyond its original intent, creating thousands of constructive CFCs. As many foreign corporations are now treated as CFCs even though they are not controlled by US persons, many minority US Shareholders (who directly or indirectly own at least 10%) have been made subject to the harsh anti-deferral rules of Subpart F and GILTI. Additionally, because US Shareholders often lack control over these constructive CFCs, they often struggle to obtain the information needed to comply with their US tax obligations.

The repeal has also impacted inbound loans intended to qualify for the portfolio interest exemption. This exemption does not apply if the interest is paid to a CFC that is related to the US borrower. IRC §881(c)(3). With the proliferation of related-party CFCs caused by downward attribution, many loans no longer qualified for the portfolio interest exemption. The US borrower could try to confirm that the shareholders of the foreign lender did not own 50% or more of a US corporation, but this was often impractical given the expansive attribution rules. As a result, many portfolio debt arrangements had to be restructured because it became difficult for foreign corporate lenders to qualify.

While the IRS and Treasury have used regulations in recent years to provide limited relief, they have been reluctant to act to significantly narrow the scope of downward attribution, believing they lack the authority to do so. The OBBBA is thus a welcome respite to many US taxpayers who have struggled under the post-TCJA landscape.

OBBBA Amendments to the Downward Attribution Rules

The OBBBA restores IRC §958(b)(4), thereby reversing the TCJA’s repeal thereof and reinstating the prohibition on downward attribution from foreign persons. This change once again prevents US persons from being treated as constructively owning stock held by foreign persons for purposes of determining CFC status. By restoring this limitation, the OBBBA narrows the criteria under which foreign corporations may be classified as CFCs and reverts to the pre-TCJA framework, which shields many foreign entities from CFC designation based solely on the existence of US affiliates.

Consistent with the pre-TCJA framework, a foreign corporation will generally no longer be classified as a CFC solely on the basis of downward stock attribution from foreign persons to US persons. However, recognizing the tax avoidance concerns that originally motivated the TCJA’s repeal (particularly the use of “de-control” structures to shift income outside the US tax net), the OBBBA introduces a protective regime under newly-added IRC §951B. This provision is designed to preserve the objectives of the TCJA while mitigating its overreach.

Under IRC §951B, two new classifications are introduced: Foreign Controlled US Shareholder (“FCUS”) and Foreign Controlled Foreign Corporation (“FCFC”).

- A FCUS is defined as a US person who owns, directly, indirectly or constructively, more than 50% of a foreign corporation (as opposed to the usual 10% threshold generally used to define US Shareholders of CFCs), applied as if downward attribution were still permitted.

- A FCFC is a foreign corporation (other than a CFC) where FCUSs own, directly, indirectly or constructively, more than 50% of the stock, applied as if downward attribution were still permitted.

After incorporating the above concepts, IRC §951B then applies Subpart F and GILTI inclusion rules in a similar manner as with traditional US Shareholders of CFCs, but only to Foreign Controlled US Shareholders and only with respect to their ownership in FCFCs. This new regime captures foreign-controlled US persons who, while not US Shareholders of a CFC under the reinstated rules, would have been under the TCJA’s broader attribution framework. The purpose is to ensure that Subpart F and GILTI rules continue to apply to US persons in cases where foreign ownership structures might otherwise allow income to escape US taxation.

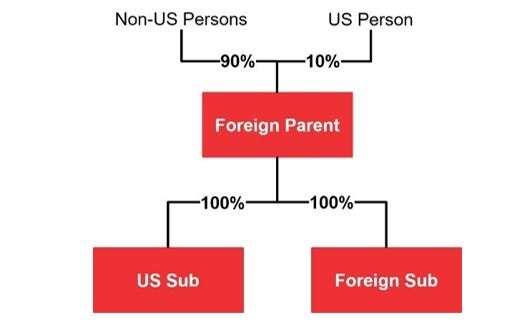

Returning to our earlier example (depicted again below), under the new IRC §951B regime and its application of the downward attribution rules, Foreign Sub is treated as a FCFC as it is more than 50% owned, constructively, by US Sub, a Foreign-Controlled US Shareholder. As US Person owns only 10% of Foreign Parent (taking into account direct, indirect and constructive ownership), US Person does not meet the 50% ownership threshold required for FCUS status and thus will no longer be subject to Subpart F and GILTI inclusions with respect to Foreign Sub’s earnings (as currently the case post-TCJA). Furthermore, as neither a US Shareholder of a CFC nor a Foreign-Controlled US Shareholder of an FCFC, US Person will no longer be subject to compliance and reporting requirements that otherwise apply to such shareholders. These results should provide long-awaited relief to minority US investors who have been subject to the CFC regime in recent years.

US Sub is treated as a FCUS based on its constructive ownership of Foreign Sub via downward attribution. However, consistent with current law, constructive ownership alone does not trigger income inclusions under the Subpart F and GILTI regimes. Therefore if, as currently illustrated, US Sub has no direct or indirect interest in Foreign Sub, then, even under the new IRC §951B regime, US Sub should still not be subject to Subpart F and GILTI income inclusions, despite it being a Foreign-Controlled US Shareholder of an FCFC.

Suppose, however, that US Sub does own stock in Foreign Sub, as depicted in the alternate diagram below. As US Sub owns a 5% direct interest in Foreign Sub, US Sub would be required to include 5% of Foreign Sub’s Subpart F and GILTI in its income, in the same manner as if Foreign Sub were a CFC. Thus while constructive ownership (including downward attribution) applies to treat Foreign Sub as an FCFC and US Sub as a Foreign-Controlled US Shareholder thereof, actual direct or indirect ownership is needed for there to be Subpart F and GILTI income inclusions. (Even if only a constructive shareholder, US Sub will likely continue to be subject to reporting requirements in a similar manner as US Shareholders of CFCs under the current post-TCJA rules, including applicable relief procedures. This must, however, be confirmed by the issuance of future regulations, referenced below.)

By subjecting only US persons with a direct or indirect interest to CFC income inclusions, the new IRC §951B regime is consistent with the “de-control” structures that Congress originally intended to target. Thus the restored IRC §958(b)(4) effectively prevents the unduly broad application of downward attribution and the new IRC §951B overrides this prohibition where US persons are controlled by a foreign parent.

Finally, IRC §951B provides the Treasury authority to issue regulations treating FCFCs and FCUSs as CFCs and US shareholders, respectively, for other purposes of the IRC, including reporting requirements and coordination with the Passive Foreign Investment Company (“PFIC”) regime.

Effective Date

The OBBBA applies the above changes to IRC §958 and §951B prospectively, effective for tax years of foreign corporations beginning after December 31, 2025.

This is particularly relevant where a foreign corporation does not operate on a calendar-year basis. For example, suppose a foreign corporation with a fiscal year-end of June 30 is treated as a CFC under current law, but will not be a CFC under the OBBBA. Pursuant to the above, the corporation would continue to be treated as a CFC from January 1, 2026, through June 30, 2026; the amended provisions of IRC §958(b)(4) and §951B will only apply beginning July 1, 2026, as that is the corporation’s first tax year that begins after December 31, 2025. Thus, any US Shareholders of this CFC will continue to be subject to applicable CFC rules (including the Subpart F and GILTI regimes and relevant reporting requirements) for the first six months of 2026.

This article does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg Industry Group, Inc., the publisher of Bloomberg Law, Bloomberg Tax, and Bloomberg Government, or its owners.

Author Information

Simon Beck is a partner and co-chair of the North America Private Capital Group in Baker McKenzie’s New York office. Paul DePasquale is a partner and Rebecca Lasky is a senior associate in the Private Capital practice group in New York. Mathew Slootsky is an associate in the Private Capital practice group in Miami.

Write for us: Author Guidelines.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Soni Manickam at smanickam@bloombergindustry.com

Learn more about Bloomberg Tax or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

From research to software to news, find what you need to stay ahead.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.