The Trump Tariffs 2.0 are expected to have a material impact on transfer pricing that might be overlooked, say Grant Thornton practitioners.

Although the anticipated Trump Tariffs 2.0 are attracting a great deal of attention, the impact that these tariffs would have on transfer pricing and vice versa is not getting the attention that it deserves. In anticipation of the tariffs, multinational corporations conducting transfer pricing analyses should identify approaches that could reduce the uncertainties presented by the proposed changes. More specifically, these companies should model the likely impact on their results in transactions with related parties, consider actions to eliminate or reduce the impact, and consider a procedural approach to any anticipated issues.

Although President-elect Trump has not yet been sworn into office, trade experts have already written numerous articles speculating about the countries, percentages, and justification for the likely new tariffs. A consensus seems to be forming that the harshest tariffs will focus on China (possibly 60%), Mexico (25-75%, with 100% on automobiles assembled in Mexico), and Canada (25%), and that a blanket 10-20% tariff will apply to most goods imported into the US. Articles are also being written about the impact on countries, customers, companies, and the global economy.

In most instances, the transfer price on transactions between related parties (“Controlled Transactions”) for tax purposes is set by reference to the net operating income of similarly situated distributors on transactions with unrelated suppliers (“Uncontrolled Transactions”). The transfer price is often the valuation used for Customs purposes. Further, the tariffs borne by a US importer (e.g., distributor) reduce the operating income of that importer/distributor. Therefore, substantial new tariffs borne by US importers on Controlled and Uncontrolled Transactions create uncertainty in transfer pricing analyses.

The Relationship Between Tariffs and Transfer Pricing

While the focus of this article is the impact of tariffs on transfer pricing, it should be noted that tariffs affect both importers that purchase goods from related parties (i.e., through intercompany transactions) and importers that purchase goods from unrelated parties. The difference is that while tariffs on imports from both related and unrelated parties put pressures on local profits, tariffs on related party transactions can also create customs and transfer pricing exposures.

For multinational corporations, tariffs and transfer pricing are inextricably intertwined. For tax purposes, the intercompany price (“transfer price”) from the seller to a related buyer determines the allocation of taxable income between those related entities. In many instances, the transfer price also becomes the customs value used for the computation of tariffs. Further, the tariffs borne by a US importer (e.g., distributor) are inventoriable or operating costs that reduce the operating income of that US importer. Due to these interactions, changes in tariffs can make transfer pricing and customs valuation compliance much more difficult and cause procedural issues with Customs and Border Patrol (“CBP”) and between the IRS and other tax authorities.

The governing principle under Section 482 of the Internal Revenue Code is the arm’s-length standard, which is met if the results realized by controlled taxpayers from their controlled transactions are consistent with the results that would have been realized if uncontrolled taxpayers had engaged in the same transactions under the same circumstances (Treas. Regs §1.482-1(b)(1)). This arm’s length approach relies upon methods and standards that compare the results of Controlled Transactions againstthe results of publicly-available Uncontrolled Transactions (“comparables”). In evaluating the comparability of Uncontrolled Transactions, taxpayers must consider the functions of the parties, contractual terms, assignment of risks, economic conditions, and property provided and services rendered by either party. The majority of transfer pricing analyses are done by way of a “lookback test” whereby taxpayers use a provisional transfer price throughout the year based on benchmarked comparables profitability to generate intercompany invoices and project that the tested party results fall within the arm’s length range of results (See Steven Wrappe and Glen Marku, True-up transfer pricing issues before the year ends (Nov. 14, 2022)). However, estimates can be inaccurate, and taxpayers are required to make adjustments, as needed, to report an arm’s length transfer price in transfer pricing documentation contemporaneous with the filing of a tax return.

Customs rules apply the duty or tariff rate to the import valuation amount. Transaction value, defined as “the price actually paid or payable for the merchandise when sold for exportation to the United States…" (19 U.S.C. §1401a(b)), is the principal methodology employed by importers when declaring a basis of appraisement to Customs. Transaction value may not be used if the buyer and seller are related, unless the importer demonstrates that the “circumstances of the sale” of the imported merchandise indicates that the relationship between the buyer and the seller did not influence the price paid or payable (19 U.S.C. §1401a(b)(2)(B)). Despite the language of the statute, most imports between related parties use transaction value based upon the representation that the relationship did not influence the terms and conditions of the sale (See Pike, Decision Time at Customs HQ: Harmonization of Customs Valuation and Transfer Pricing Rules, 1 Customs and International Trade Bar Associate Quarterly Newsletter 1 (Fall 2006).

In transfer pricing analysis, tariffs are generally recognized as an inventoriable or operating cost that reduces the operating profit of the entity bearing the tariff since they are typically a line item in the cost of goods sold (“COGS”). Tariffs also influence intercompany pricing and risk allocation. When tariffs are imposed on goods transferred between related entities, the cost burden typically falls on the importer unless explicitly allocated otherwise in an intercompany agreement. This additional tariff cost must be factored into the transfer price, ensuring that the price paid reflects market conditions and complies with customs valuation rules.

The allocation of risks, including those related to tariffs, is a key determinant of transfer pricing outcomes. Transfer pricing regulations require that risk be allocated in line with the economic substance of transactions. This generally means that the entity assuming the risk must have the capacity to manage that risk, including the necessary functions, assets, and personnel.

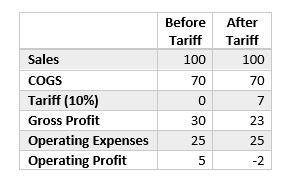

Illustration of the impact of tariffs. It may be helpful to consider a simple example to illustrate the impact of a new tariff on intercompany transactions. As seen in the table below, adding a 10% tariff borne by a distributor, and not pushed through to its customers, can push a distributor from a profit position of 5 to a loss position of 2.

Table 1: Impact of tariff with no pass-through to customer

Impact of Trump Tariffs 2.0 on Transfer Pricing

The new tariffs imposed by the Trump administration are expected to impact transfer pricing on several fronts: (a) impact on comparables results, (b) impact on tested party results, and (c) government reaction to post-importation adjustments. Differences from previous and existing tariffs, especially the expectation of blanket tariffs on nearly all goods from all countries, may affect company strategies.

Impact on comparables results. The selection of comparables and adjustments made to enhance comparability are an essential element of most transfer pricing analyses.Changes in government policies, such as tariffs, can have a differential impact on companies in the same industry or sector.Hence, tariffs are expected to affect comparability analyses.

- Changes in comparables financial results—Tariffs disrupt typical supply and demand dynamics, altering market prices for goods and services. Benchmarking studies rely on historical or peer data to establish arm’s length pricing, but these comparables may no longer reflect the new, tariff-affected realities. Tariffs can increase the cost of imports, making prior pricing data irrelevant or inaccurate for determining appropriate intercompany pricing.Additionally, tariffs that specifically target certain industries (e.g., steel or technology) can create regional price disparities, complicating the use of international benchmarks.

- Limited availability of relevant comparables—When tariffs lead companies to restructure supply chains or shift production locations, the operational profiles of comparable companies may no longer align with the tested entity. For example, firms that continue importing goods despite high tariffs might face significantly higher costs than competitors that source locally or regionally. As a result, finding comparable companies with similar operating circumstances becomes more challenging.

- Impact on profit margin benchmarks—Tariffs can compress profit margins for importers, as increased costs might not be fully passed on to customers. This can make it difficult to align with traditional profit-based analyses and benchmarks, potentially leading to misinterpretations of profitability and pricing. Benchmarking studies may need to be adjusted to reflect the unique pressures on businesses affected by tariffs, but such adjustments require robust justification to satisfy regulatory scrutiny.

- Increased complexity of regional comparables—Regional comparables may need to account for tariff-driven shifts in trade flows and production. For instance, if companies in a region switch to domestic production, this could change the cost structures and pricing strategies of peers, invalidating existing benchmarks. Adjusting for these changes often involves creating new, region-specific benchmarking approaches that incorporate tariff effects, requiring additional time and resources.

Impact on tested party results. As noted above, tariffs are inventoriable or operating costs generally reflected in the transfer pricing analyses. As such, changes in tariff policy will affect tested party results and adjustments that may be required.

- Tested party margins—Under the comparable profits method (“CPM”), a tested party must be selected and analyzed.Tariffs are generally an added inventoriable or operating cost captured in the costs of goods sold.As such, if the tested party is the US importer (e.g., a distributor), the tested profit margin will be negatively impacted. If the tested party is the exporter (e.g., a contract manufacturer), the profit margin of the US importer may be negatively impacted, but the tested profit margin of the exporter is not affected.

- Adjustments for tariff costs—Transfer pricing rules typically require adjustments to remove extraordinary costs or non-recurring factors. However, determining how to account for tariffs in comparable analyses can be subjective and contentious. For example, should tariffs be treated as extraordinary, or should they be built into long-term pricing models? Tax and customs authorities might differ in their interpretations, leading to inconsistencies and potential disputes.

Government reaction to post-importation adjustments. Changes in tariff policy are expected to have a noticeable impact on intercompany transactions and profits of multinationals.As taxpayers make adjustments to mitigate the impact of US tariffs, government agencies in the US and overseas are likely to take notice and issue further guidance to protect their interests.

- Customs and Border Patrol (“CBP”) reaction—If the taxpayer sets its customs valuation based on its transfer pricing analysis, an upward transfer pricing income adjustment will require a downward customs valuation adjustment. Importers have various options to report transfer pricing adjustments to CBP. The Reconciliation Program is probably the most efficient manner of accomplishing this goal.Generally, under the Reconciliation Program, the importer flags importation entries and declares an initial temporary value at that time to be completed or reconciled, no later than 21 months after importation. Importers, however, may report adjustments through post-entry corrections to the customs entry documentation or by filing protests for downward price adjustments. Importers may also make a voluntary “prior disclosure” of a violation to CBP to report a previously undeclared value or price adjustment in exchange for significantly mitigated customs penalties (generally capping the penalty to the interest owed on revenue loss). The interplay between transfer pricing and customs valuation under the new tariff regime may trigger an iterative process of adjustments to transfer pricing and customs valuation.

- Tax treaty partner reaction—Under US transfer pricing rules, an upward transfer pricing adjustment to the income of a related party necessarily produces a downward adjustment to the income of the other transacting related party, but the tax authority in the other involved country may not agree to the change. Under the US tax treaty network, a US taxpayer can request the IRS’s assistance to endeavor to achieve a downward adjustment to the income of the related party in a tax treaty country. A treaty dispute resolution mechanism, known as the mutual agreement procedure, allows treaty partners to eliminate double taxation arising from transfer pricing disputes. Based on information discussions with some tax authorities, it is likely that they might object to the reduced tax revenues caused by the self-enriching tariffs imposed by the US government. After all, tariffs that persist long enough could inflict economic harm on other countries by limiting or reducing demand for goods produced in those countries. Shifting the cost of tariffs to other tax jurisdictions through transfer pricing mechanisms will likely lead to some difficult discussions among tax authorities in bilateral negotiations between treaty partners in the MAP or in bilateral advance pricing agreements as taxpayers seek to avoid double taxation.

Potential Actions to Mitigate the Impact of Trump Tariffs 2.0

In response to previous increased tariffs in 2018, companies employed a number of strategies to eliminate or reduce the impact of tariffs. Due to the blanket aspect of proposed Trump Tariffs 2.0, some of these actions may not be as effective as before.

- Pass tariff costs on to customers – Importers can pass the economic impact of a tariff on to its customers through a price increase.However, competing products not subject to the same level of tariffs could make it difficult for importers to raise prices.

- Stockpile inventory – Some importers have already begun to purchase large volumes of products for delivery before the effective date of any new tariffs. Many companies can be expected to use this approach, but it is only a temporary solution.

- Exclusions/re-evaluate product classification – Some importers have previously been able to avoid the tariffs by seeking exclusions through the US Trade Representative or by re-evaluating the classification of imported good to a one not impacted by tariffs. Under the blanket tariffs currently anticipated, the opportunity for re-classification seems less promising than before.

- Operational changes – Some companies made operational changes in response to the recent tariff increases. Companies with flexibility changed suppliers or moved supply chains to avoid tariff impact. Others simply stopped selling goods in the US that were made unprofitable by the tariffs.The moving of supply chains or supplier relationship is likely to be less effective in a blanket tariff environment.

- First sale – Under the first sale rule, importers set the customs valuation based on the earliest transaction in a series of transactions resulting in importation into the US, effectively allowing the importer to eliminate the intermediate entity’s profit from the dutiable value. However, if the parties to the first sales transactions are related, the goods must be transferred at arm’s-length prices.

- Customs valuation planning – Evaluate whether alternative customs valuation methods (e.g., computed value or deductive value) can provide flexibility under high tariffs. Explore whether adjustments for non-tariff components (e.g., royalties, licensing fees) can help reduce declared import values in compliance with customs regulations.

- Sharing tariff impact between related parties – Exposure to tariffs can be understood and interpreted similar to other exogenous risk factors (e.g., regulatory changes, currency fluctuation, or widespread epidemics).Unrelated parties may share the impact of tariffs through a reduction in the transfer price; transfer pricing rules also allow related parties to allocate the impact of tariffs between the parties. Although allocation of the tariff risk does not avoid the tariff impact, it may reduce the overall impact and be beneficial for transfer pricing compliance purposes.

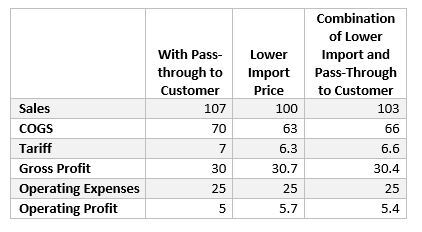

Table 2: Illustrates some scenarios of risk mitigation

Next Steps

The Trump Tariffs 2.0 are expected to have a material impact on customs and transfer pricing, and companies have a window of opportunity to establish mitigation plans.

This article does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg Industry Group, Inc., the publisher of Bloomberg Law and Bloomberg Tax, or its owners.

Author Information

Steven C. Wrappe is the National Technical Leader of Transfer Pricing in Grant Thornton’s National Tax Office and an adjunct professor in the New York University and University of California-Irvine tax programs. Marenglen Marku is a Ph.D. economist and principal in Transfer Pricing at Grant Thornton as well as an adjunct professor at DePaul University’s Kellstadt Graduate School of Business.

“Grant Thornton” refers to the brand under which the Grant Thornton member firms provide assurance, tax and advisory services to their clients and/or refers to one or more member firms, as the context requires. Grant Thornton LLP is a member firm of Grant Thornton International Ltd (GTIL). GTIL and the member firms are not a worldwide partnership. GTIL and each member firm is a separate legal entity. Services are delivered by the member firms. GTIL does not provide services to clients. GTIL and its member firms are not agents of, and do

not obligate, one another and are not liable for one another’s acts or omissions. Please see www.gt.com for further details.

We’d love to hear your smart, original take: Write for us.

Learn more about Bloomberg Tax or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

From research to software to news, find what you need to stay ahead.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.