The corporate alternative minimum tax, enacted in 2022 as part of the Inflation Reduction Act, imposes a 15% minimum tax on “adjusted financial statement income” for certain large corporations and has multiple shortcomings. CAMT is conceptually flawed, involves very high compliance costs, does not meaningfully change corporations’ incentives, and raises little revenue.

We analyze the shortcomings of CAMT using data from a Tax Executives Institute (TEI) survey. This article, the first of two, focuses on CAMT’s conceptual problems and compliance costs based on survey results. A second article will examine CAMT’s impact on corporate tax planning and estimated tax revenue, also using survey results.

TEI sent the survey to select TEI members, chosen on the basis of having an interest in CAMT as a policy issue, or suspected CAMT liability. TEI’s membership consists primarily of tax directors, vice presidents of tax, and similar roles at large and mid-sized companies across a wide range of industries. These professionals are responsible for implementing CAMT calculations, developing internal compliance and planning models, and signing off on returns. We received responses from 64 individuals, 60 of which completed it entirely, 23.4% of whom work for companies that have paid CAMT.

The survey is designed to capture both one-time implementation costs and steady-state annual compliance costs. The results suggests that CAMT has created significant new compliance costs without clearly delivering its intended benefits. Survey respondents report substantial one-time and ongoing expenses for CAMT calculations—often incurred by companies that rarely, if ever, owe CAMT. As a result, CAMT now accounts for a nontrivial share of overall tax compliance efforts. The qualitative comments consistently highlight a common theme: CAMT is complex, costly, and frequently burdens firms that pay little to no CAMT. As one respondent noted, CAMT is a “compliance burden and nightmare.”

Conceptual Problems with Taxing Book Income

Long before CAMT was enacted, many accounting academics raised concerns about using financial accounting income as part of the corporate tax base (for critiques of CAMT, book-minimum-tax proposals, and related efforts to tax financial accounting income, see, e.g., Hanlon, M. and J. Hoopes. 2021. Open Letter of Concern Regarding Corporate Profits Minimum Tax. Letter written to Senators Wyden and Crapo, and Representative Neal and Brady, signed by 264 other accounting academics; Hoopes, J. (2021). Written Testimony for Creating Opportunity through a Fairer Tax System. Senate Subcommittee on Fiscal Responsibility and Economic Growth (Apr. 27, 2021). Financial accounting rules are designed to provide investors and other stakeholders with decision-useful information about company performance and stewardship. In contrast, tax rules aim to raise revenue and implement policy preferences. These two sets of rules derive different measures of “income” that have fundamentally distinct purposes.

This conceptual problem underlies many of CAMT’s flaws. By taxing financial accounting income, CAMT brings into the tax base a host of book-tax differences that Congress never intended to tax. Paradoxically, CAMT then carves out numerous exceptions, explicitly exempting many of these differences. The result is a law that was designed to patch an exemption-ridden tax code, but which creates another patchwork of exceptions, equally susceptible to lobbying and political pressure.

Because CAMT’s high complexity and reliance on Treasury guidance for defining critical elements allows for significant post-enactment lobbying. Treasury, through the regulatory process, effectively determines the scope of many exclusions, allowing ex-post pressure to shape the law’s implementation.

The entanglement of these fundamentally different systems leads to several consequential problems. First, linking tax liabilities to book income reduces the value of financial reports for investors. When managers understand that recognizing more accounting income directly increases their tax obligations, they have a strong incentive to adopt conservative assumptions that minimize reported earnings rather than those that best reflect economic reality. Over time, this bias has the potential to degrade the quality of reported earnings, ultimately making capital markets less efficient.

Second, book income is a poor base for efficient tax collection. Financial accounting income includes unrealized gains and other non-cash items, while smoothing economic performance over time. Taxing these amounts can impose cash tax obligations that are not matched by cash inflows, distorting the tax system and potentially creating liquidity problems for affected firms.

Third, using book income in the tax base creates competitive and structural distortions. Various elements, such as net operating loss rules, cross-border income, and public-versus-private status, all interact differently with book and tax systems. A book-based minimum tax can disadvantage US-domiciled multinationals relative to foreign competitors and can create incentives to stay private or avoid US capital markets altogether.

Finally, and perhaps most concerning over the long term, a book-based tax risks politicizing financial accounting standard setting. As we emphasized in the open letter to Senator Wyden, using financial accounting income in the tax base effectively gives the Financial Accounting Standards Board partial control over the US tax base while simultaneously encouraging Congress to pressure the FASB to adopt tax-motivated standards. This dynamic undermines the independence of standard setting and increases the likelihood that accounting rules will be shaped by fiscal or political goals rather than the need to maximize the quality of information for capital markets.

CAMT is built on a conceptually flawed foundation. If policymakers believe the corporate tax code is overly generous or poorly targeted, a more effective approach would be to fix the tax code directly—by reassessing specific preferences, credits, and structural provisions—rather than grafting a book-based minimum tax onto an already complex system.

What Proportion of Companies Pay CAMT?

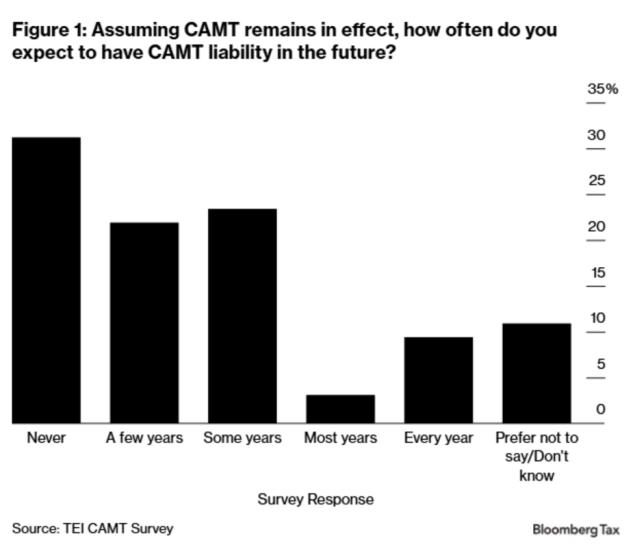

The survey asked whether each respondent’s company incurred a CAMT liability to date and, if so, how frequently they expected to face CAMT in the future. We found that only 23.4% of respondents reported any positive CAMT liability to date. When asked about the future, even fewer respondents expected their firms would be subject to CAMT. The majority of firms have not yet had a CAMT liability and expect to have one only sporadically. Only 12.5% reported that they expect to pay CAMT most or all years. See Figure 1.

This pattern mirrors the 10-K evidence: A relatively small number of companies actually pay CAMT, but many more must evaluate their exposure and build the infrastructure to compute adjusted financial statement income. The implication is that the administrative apparatus of CAMT—systems, modeling, documentation, and controls—extends far beyond the small set of firms that pay the tax.

Implementation Costs

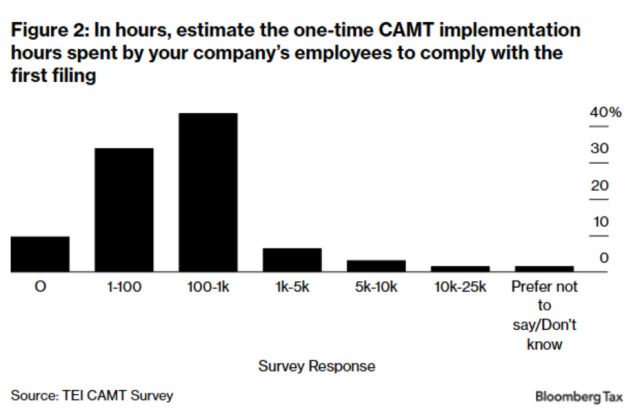

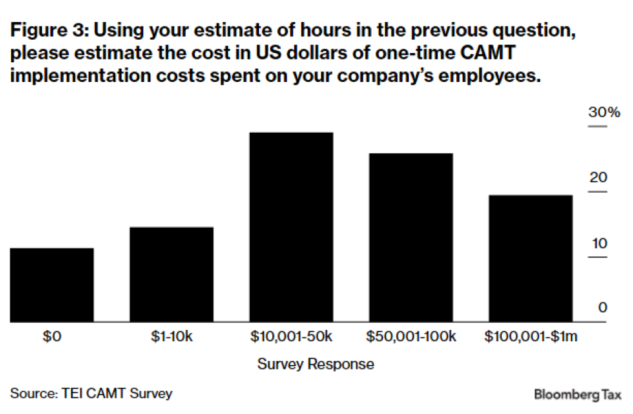

The survey asked respondents to estimate their one-time CAMT implementation costs, using ranges rather than exact figures. They reported both internal hours/costs incurred by company personnel and external costs paid to advisors, software vendors, or other third parties. See Figures 2 and 3.

The median CAMT-affected company reports between 100 and 1,000 internal hours devoted to initial CAMT implementation, with a significant share of firms indicating even more hours. Figure 3 shows that nearly 20% of respondents reported compliance costs exceeding $100,000 from internal one-time implementation costs.

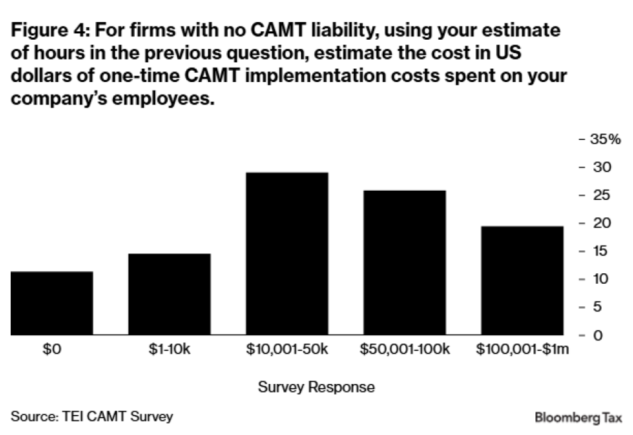

Many firms with no CAMT liability still report nontrivial hours/costs required to comply with this new law. Figure 4 replicates Figure 3, but only for firms with no CAMT liability, and suggests substantive administrative costs even for firms who end up remitting no tax.

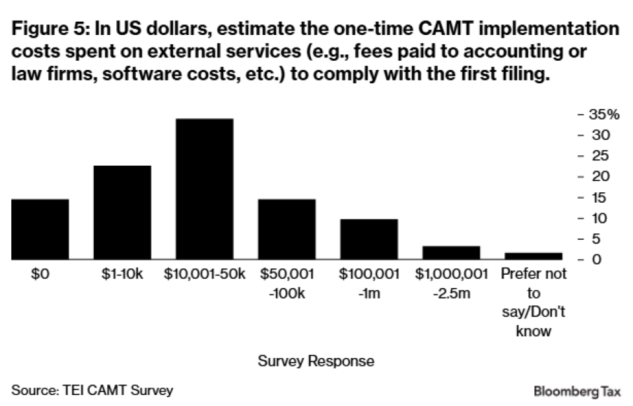

Firms report substantial external implementation costs. Nearly one-third of respondents place their one-time external spending at more than $50,000, reflecting fees paid for outside advisors, IT consultants, and CAMT-specific software. At the upper end, two respondents report one-time external CAMT implementation costs exceeding $1 million.

These implementation costs are, by construction, purely administrative. They do not correspond to any incremental tax revenue raised, relative to a world in which the same dollars of tax liability were collected through a better-designed, income-based minimum tax embedded in the regular corporate tax system. The costs represent resources diverted from productive investment, internal tax department modernization that might have been undertaken on a more rational schedule, or other compliance priorities.

Steady-State Compliance Costs

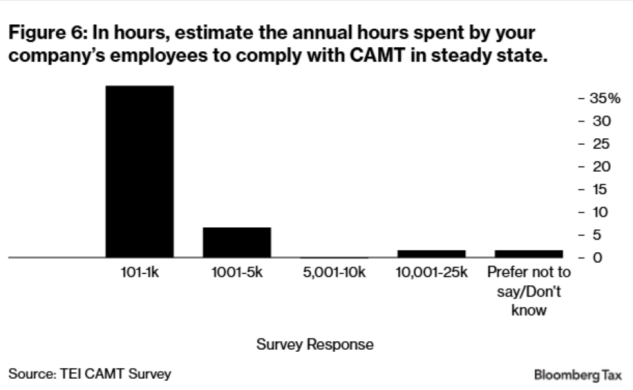

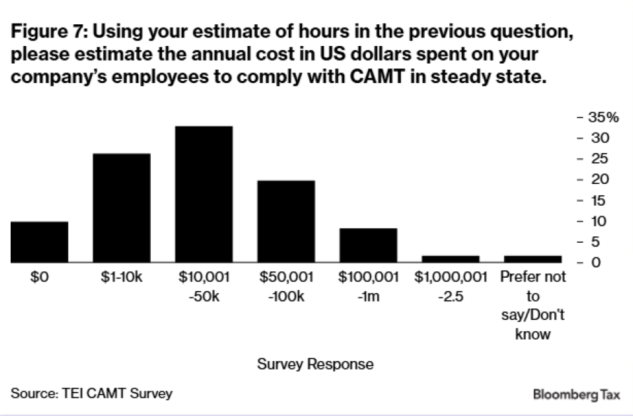

The costs above represent one-time costs that are not recurring. Next, we ask respondents to estimate steady-state annual compliance costs for CAMT, again broken into internal and external components. The most common CAMT-affected company reports annual internal compliance hours in the 101 to 1,000 hours category, with five respondents reporting more than 1,000 hours per year devoted to CAMT once systems are in place. See Figure 6. In dollar terms, respondents’ most frequently chosen ranges imply ongoing internal costs on the order of $10,001 to $50,000 per year for the typical firm. See Figure 7.

External annual spending, while typically lower than one-time implementation costs, is still meaningful. Out of 61 respondents, 20 (32.8%) indicate that external fees are between $10,001 and $50,000, and 18 (29.5%) indicate that external fees are at least $50,001.

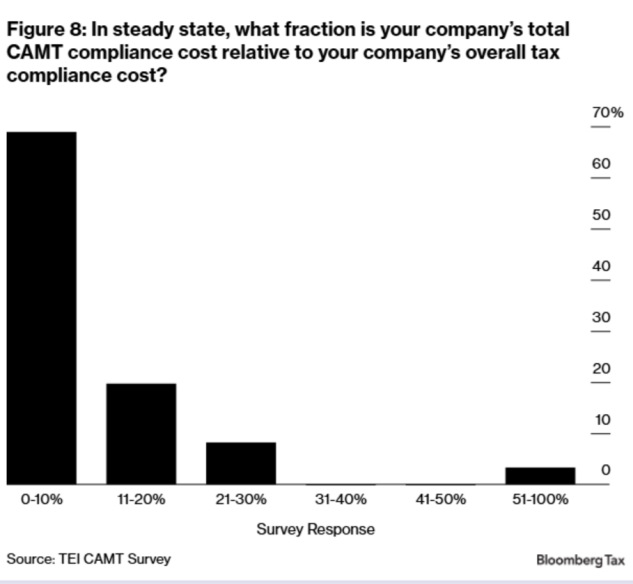

Finally, to put these numbers in context, the survey asked respondents what fraction of their overall corporate tax compliance costs were attributable to CAMT in steady state. See Figure 8. Using a slider to select any value between 0% and 100%, the median response was 10% percent. Twenty percent of respondents reported that CAMT accounts for 11% to 20% of their total tax compliance costs; 8.2% reported that CAMT accounted for 21% to 30%; and 3% (two respondents) report that CAMT costs exceeded half of their total tax compliance burden. When a single, narrowly targeted minimum tax absorbs such a large share of the tax department’s resources, it becomes difficult to claim that its administrative costs are modest.

CAMT Comments

The survey included an open-ended question asking respondents to comment on CAMT’s compliance costs for their business.

The comments on this final question paint a consistent picture of the CAMT as a costly, resource-intensive add-on to an already overloaded tax function. What particularly frustrates many respondents is that these burdens fall even on companies that are nowhere near having a CAMT liability and may never pay any meaningful amount of CAMT; they still must build systems and file forms simply to prove they are out of scope. For such firms, CAMT compliance is perceived as pure deadweight—a substantial, recurring drain on time and money that provides no discernible benefit to the organization or to the government, especially because any CAMT paid can often be recovered when regular tax later exceeds the CAMT amount.

Takeaways

The survey responses suggest that CAMT has imposed substantial new compliance burdens, even among corporations that do not ultimately pay the tax. Roughly one-third of respondents report paying CAMT so far, and among those in scope, most expect to face a liability only intermittently. One-time implementation was typically material: a majority of firms report hundreds to thousands of internal hours and mid-five to low-six-figure internal and external costs to set up CAMT processes. In steady state, respondents still report sizable recurring costs in both hours and dollars, with many characterizing CAMT as an additional full computation layered on top of Pillar 2, GILTI, and other minimum-tax regimes. Firms estimate that CAMT now accounts for a nontrivial slice of their overall tax compliance budget, with a median of around 10%, even though most companies either never owe CAMT or only owe it in a subset of years.

This article does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg Industry Group, Inc., the publisher of Bloomberg Law, Bloomberg Tax, and Bloomberg Government, or its owners.

Author Information

Andrew Belnap is an assistant professor of accounting at University of Texas at Austin. Jeffrey L. Hoopes is a professor of accounting at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. They are both members of the Tax Policy Network.

* Although TEI members participated in the survey, none of the authors’ statements or survey results mentioned in this article represent an official position of TEI. Given the sensitive nature of CAMT and tax information, we did not include any identifying details in our survey, so respondents could be ensured anonymity. The survey, administered via Qualtrics, ensured complete anonymity, such that (1) respondents were informed that no identifying information, including IP addresses, was collected; (2) responses would be used only in aggregate form; and (3) any quoted open-ended comments in publications would not be linked to other answers or identifying information. We thank TEI for their help in distributing this survey.

The authors have no financial or other conflicts of interest to disclose. The authors appreciate the support of the Tax Policy Network.

Write for Us: Author Guidelines

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Soni Manickam at smanickam@bloombergindustry.com;

Learn more about Bloomberg Tax or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

From research to software to news, find what you need to stay ahead.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.