Dr. Janice Jaferian and Christopher J. Leisner discuss how enterprises may be able to expand funding their R&D programs by securitization of their IP licenses.

Corporations can continue, or even expand, their R&D programs in an era where future government subsidies may be lower than at historical levels. Following-on to a prior article, Guiding Private Equity Companies “Third Bite” At The R&D Apple (Christopher J. Leisner, Professional Perspective (2023)), this article discusses a blend of three primary business sectors: (1) research & development, (2) technology transfer licensing, and (2) enhanced cash flows through securitization of specific asset classes.

There are multiple funding sources of R&D innovation in addition to private enterprises. In the US, R&D innovations can be sourced from government agencies such as the Department of Energy (DOE), Department of Defense (DOD), Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The collection of US national laboratories and universities share innovations using government subsidies and tax credits to augment their R&D funding.

Whether through a university grant, or a direct corporate R&D award from a federal agency, there is an expectation that future funding from the US federal government will be lower than recent historical levels (Razan Alkhazaleh, Konstantinos Mykoniatis, and Ali Alahmer, The Success of Technology Transfer in the Industry 4.0 Era: A Systematic Literature Review, J. Open Innov., Vol. 8, Iss. 4 (Dec. 2022); see also Clare Zhang, Project 2025 Outlines Possible Future for Science Agencies, Am. Inst. of Physics (Nov. 2024)). Similarly, other large-scale R&D initiatives, such as the European Commission’s multi-year “Technology Sovereignty” European R&D initiative, with an estimated budget of €800 billion, are competing with other large governmental spending priorities (European Commission: Directorate-General for Research and Innovation, Jakob Edler, Chapter 8: Technology Sovereignty of the EU: Needs, Concepts, Pitfalls and Ways Forward of Science, research and innovation performance of the EU, 2024 – A competitive Europe for a sustainable future, Pub. Office of the EU (2024)). However, there is an alternative R&D funding source outside of government agency support.

R&D – Growth Driver and Capital Resource Absorber

As R&D creates commercializable innovations to satisfy market demands, it also generates valuable intellectual property (IP), such as technical know-how, trade secrets, and patents. Such IP is embedded in the enterprise’s core products, services or manufacturing processes, and is largely utilized within the enterprise’s commercial operations. Often, there may be an abundance of under-utilized, unused, or alternative-use (non-competing) IP that could have significant market value to others. Successfully out-licensing a company’s R&D innovations to alternative-use companies is often a key focus of a company’s Technology-Transfer Program. It mutually benefits both the IP inventor (“Licensor”) and IP recipient (“Licensee”) by expanding existing markets, entering emerging markets, or creating new markets while establishing strategic relationships that avoid costly litigation. Such licensing benefits the Licensee by reducing its cost of original invention and accelerating its time-to market with new products and services. Simultaneously, it benefits the financial performance of the Licensor by creating royalty revenue streams while also enhancing its reputational value as a knowledge creator and market expander.

R&D Spending and R&D Intensity

R&D spending is indicative of the strategic emphasis enterprises place on innovation as the engine to fuel their competitive market position and overall performance. The metric “R&D Intensity,” is calculated as a percent of overall enterprise revenues: (R&D Enterprise Expenditures/Total Revenues) x 100. It is a reflection of an enterprise’s strategic priorities and signifies its capabilities to effectively evolve its technology to meet shifting or emerging market demands.

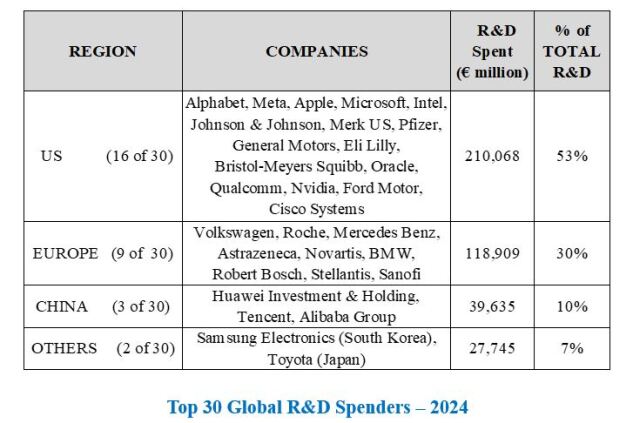

Based on recent European Commission data of the global Top 100 R&D spenders, US companies dominate in R&D spending, but Europe exceeds that metric when compared to China and others.

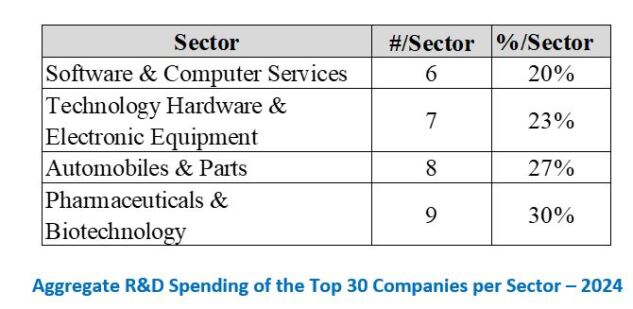

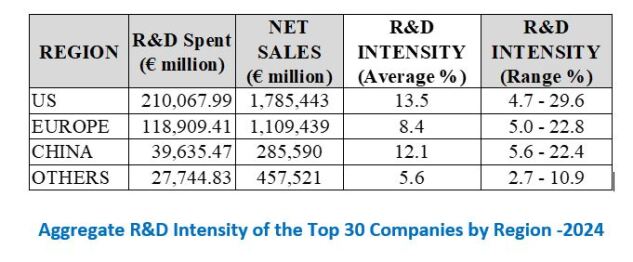

The following three charts summarize R&D spending by top global spenders, sector, and region (based on data derived from European Comm., The 2024 EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard (Dec. 2024)).

R&D intensity examples:

- The top 3 US companies with the highest R&D intensities were: Intel: 29.6; Eli Lilly: 27.3; and Meta: 27.0.

- The lowest US company R&D intensity was: Ford Motor: 4.7.

- The highest and lowest R&D intensities amongst European companies were: Astrazeneca: 22.8; and BMW: 5.0.

- The highest and lowest R&D intensities amongst Chinese companies were: Huawei Investment & Holding: 22.4; and Alibaba: 5.6.

- The highest and lowest R&D intensities amongst companies in the rest of the world were: Samsung Electronics (South Korea): 10.9; and Toyota Motor (Japan): 2.0.

R&D Commercialization and Technology Licensing—"First and Second Bites”

Revenues from commercial operations arise from a company’s historical R&D investments that create products and solutions that satisfy market needs, what we refer to as the “First Bite of the R&D Apple.”

In many instances, there is an abundance of additional alternative uses of a company’s R&D-based innovations beyond its commercialization revenues that could have significant profit enhancements to other companies (“Second Bite”). For example, in the private sector, IBM has generated over $27 billion in IP licensing revenues since 1996, with some years exceeding $1 billion. The estimated volume of US technology licensing is estimated to exceed $56 billion (IBIS World, Intellectual Property Licensing in the US—Market Size 2002–2027).

Across the domain of US government-sponsored innovation, there is a long history of the creation and sharing of alternative-use innovations that launched or expanded massively successful commercial enterprises, such as:

- Global positioning systems: used for defense as well as civilian navigation systems for transportation, agriculture, and emergency response systems;

- Radar technology: foremost for military use then shared for civilian air traffic control;

- Scanning machines: initially for serving military diagnostics then dispersed into civilian sector hospitals and research centers; and

- Semiconductor and integrated circuit technology: driven primarily for military computing then becoming the cornerstone of general-purpose computers, smartphones, and household appliances.

In the private sector, US companies account for about 35% of global licensing value in an overall market valued at $150B in 2024. And about 50% of Fortune 500 companies engage in patent licensing (PatentPC).

Tech-transfer licenses may encompass a wide array of licensed rights, including:

- Rights to use proprietary know-how, trade secrets, patents, or copyrights (IP), often referred to as ‘make or have made’ rights;

- Rights to make and commercialize derivative works;

- Rights to sub-license the IP; and

- Technology support/training and ongoing knowledge transfer services.

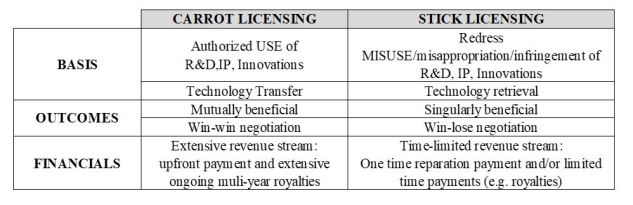

When the inventing enterprise can identify alternative (non-competing) uses for its R&D innovations beyond its own needs, properly structured technology-transfer licensing programs, including field-of-use licenses, can become an additional source of revenues. Such innovations could be licensed to the economic advantage of the licensee, otherwise known as “Carrot Licensing”.

Carrot Versus Stick IP Licensing

In contrast to Carrot Licenses, there are instances where the owner of the IP (frequently related to patented technologies) asserts its legal ownership rights on the unauthorized user of its innovations. Whether this unauthorized use is advertent or inadvertent, it becomes subject to settlement payments (if not enjoined via injunction or other non-adjudicated stoppage to cease its unauthorized use). These settlements are commonly known as “Stick Licenses”. Patent assertion litigation in the US is a multi-billion-dollar market and has attracted financial investors who often only acquire the rights to the patent claims and do not use those IP assets for commercialization purposes. Such patent aggregators are referred to as “Non-Practicing Entities”.

At the core of the distinction between Carrot versus Stick licenses is that the licensor’s innovations are seen by the Carrot Licensee as IP worth acquiring and applying to legitimately enhance its commercial operations. In Stick Licensing, the unauthorized user may also aspire to enhance its commercial operations, but by rather devious means. The misuser/infringer may be attempting to reduce its own R&D and development expenses, leverage the technological advances of others, increase market share, and/or shortcut time-to-market schedules by illegitimately absconding others’ IP. It is the prerogative of the IP owner whether to license that misused/infringed IP or not. As such, in a Stick Licensing setting, the unauthorized user may become a licensee by obtaining legal rights to the IP and paying settlement royalty fees to the licensor as redress for IP misuse. The then-authorized user of the IP in a Stick License is sometimes referred to as having gained a ‘Freedom to Operate’ license. While the majority of Stick License negotiations arise from an assertion of patent rights, there are other situations where the underlying technology has been legally adjudicated as an improperly obtained trade secret, sometimes referred to as an ‘ill-gotten gain.’

As such, the motivations for the licensee to continue to meet its contractual future payment obligations to the licensor are dramatically different for a Carrot versus a Stick Licensee. A Carrot Licensee is highly stimulated to continue its license as the enabler of its commercial successes. For the Stick Licensee, however, the fees may be seen as a financial or reputational drawback to be overcome, despite the utility and value of the initially ill-gotten IP.

Carrot Licensees Provide Reliable Future Royalty Revenues

As the preceding chart lays out, the long-term licensing relationship established in a tech-transfer Carrot License scenario creates a more predictable and reliable stream of future cash flows. This potential multi-billion-dollar estimate is of the annual royalty fee revenues recognized only in the current year’s income statement. Future license contract obligations owed to the licensor are not reported by the licensors on their balance sheet. For the US alone, under the hypothetical assumption that the average duration of an IP license is five years, the potential total remaining future licensing obligations could exceed $200 billion of off-balance sheet contract receivables.

In a fashion similar to the securitization of home mortgages by Fannie Mae, as well as securitized trade receivables by commercial bonding entities, portions of this $200 billion in unrecorded future Carrot License cash flows could be sold with the proceeds used to subsidize ongoing R&D programs (the “Third Bite”).

“As a technology attorney with decades of experience in all areas related to IP, I have assisted clients to procure, protect, exploit, license and securitize their IP rights and technologies. I have observed the efforts of other entities to also bring IP-related assets to the capital markets. It is important to recognize that legal protections (such as patent claims, copyrights and secrecy agreements) are enhancements to the reliability of the underlying licensee’s ‘promise-to-pay’. Securitization can unlock the value of IP in the form of licensing free cash flows from existing and future licenses and provide supplemental sources of self-funding R&D to support and spur innovation.”

(Rory J. Radding, partner at Maschoff Brennan).

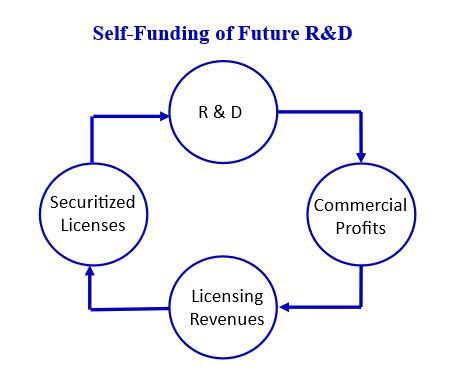

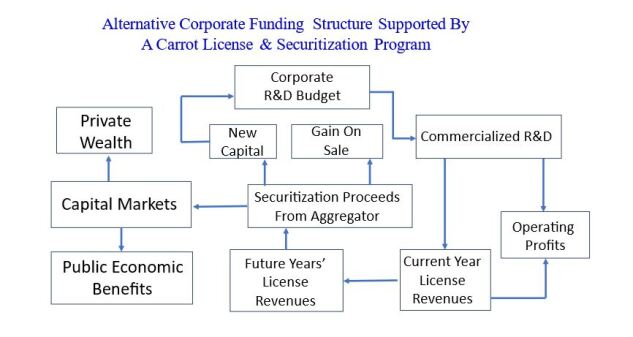

The chart below outlines how securitizing current high-tech Carrot License obligations could fund future R&D and even accompanying tech-transfer licensing programs at corporations, independent of any potential future governmental support.

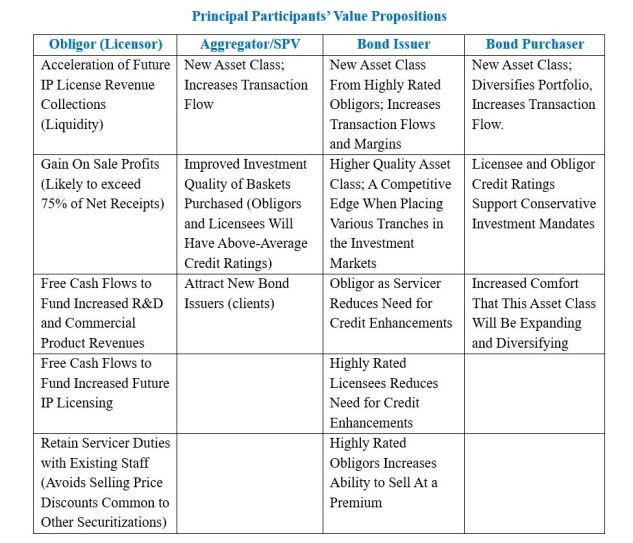

Securitizing Carrot Licenses—Benefits to the Licensor/Obligor

The principal reason to securitize any asset is typically to enhance liquidity in the current period. In most securitization transactions, anticipated future cash flows are sold to a third party to create a bankruptcy-remote standing of the future payment obligations that bond issuers and their underwriters require. Securitizations are distinct from factoring (e.g., of accounts receivables) where the factoring transaction is a loan, whereas securitization is a true sale.

In addition to an infusion of cash (a balance sheet benefit), given the unique nature of Carrot Licenses, their securitization generates a potential gain-on-sale profit (an income statement benefit). Because future Carrot License royalty payments are not posted to the balance sheet (under US GAAP or IFRS), there is no material historical cost basis for the contract obligations that are sold. For discussion purposes, if these future cash flows are sold at a net present value, less any sale premium the buyer might require, the gain on sale could likely exceed 70%, which is likely higher than the operational profit margin of the selling company.

For certain sellers with accumulated short-term losses, there could be an additional tax benefit where the profitability of these transactions pushes net losses or modest net income up to a level where current year taxes owed could be offset by prior years’ losses.

As a result of securitizing these off-balance sheet future cash flows, with the increased liquidity and other GAAP benefits, the licensor has generated its ability to fund future R&D, as well as enhanced tech-transfer out-licensing programs. Such increased R&D and tech-transfer licensing can generate future new securitizable Carrot License transactions – what in the financial markets is also referred to as ‘flow’' Over time, such Carrot Licensing benefits would likely increase going forward.

Securitizing Carrot Licenses—Benefits to Capital Markets

While increasing a company’s balance sheet value and current year’s net income (micro-economics), securitizing carrot licenses also generate benefits in the capital markets overall (macro-economics). The addition of a new asset class (future Carrot License Royalties) helps to diversify the capital markets, which is typically seen as a positive. Given that carrot licensors and licensees are both typically highly rated credit entities, the quality of this asset class is likely superior to many other securitized asset classes in the market.

Further, because the Carrot Licensee typically improves their bottom line by entering into the tech-transfer agreement in the first place, much like a residential homeowner who wants to continue to dwell in their home, Carrot Licensees have an incentive to make their future royalty payments on time. This addresses a primary concern in securitizations (reliable future payments) that if seen as a risk, can lead to additional transaction expenses, often referred to as credit enhancements.

For the bond issuer, and the bond purchaser, this higher confidence in future payment obligations enhances the issuer’s potential bond selling price when compared with contemporaneous competing bond issuances. For the bond purchasers who often have strict risk-management mandates (e.g., retirement/pension funds), this new asset class provides them with better investment placement options without the need for potential credit enhancements that they would need to rely upon to protect their fiduciary transactions.

For these and other reasons, Carrot License contract receivables, as an asset class, generate investment market-level benefits that are not yet being realized.

The chart below helps to present the broad array of benefits arising from Carrot License securitizations.

Given the specific nature of technology-transfer licenses, this new securitization asset class generates positive financial benefits for each potential participant in the securitization transaction flow.

Real World Applications (PE Firms, Multi-Nationals)

Since 1973, the Licensing Executive Society International (LESI), has been the largest professional association of intangible asset licensing executives and professionals. LESI has been growing and is now active in more than 90 countries, serving over 6,500 licensing entities in 33 national and regional societies. Annual technology licensing—along with its attendant confidential scientific know-how, trade secrets and published patent protections—is thought to generate annual revenues in excess of $300 billion globally.

For global private equity entities, including sovereign wealth funds, which have invested hundreds of billions in R&D-centric commercial entities, their stockpiles of alternative-use licensable innovations are sizable within their own structures. Taken as a collective market sector, their Carrot Licensing and securitization potential could exceed $500-$750 billion. Accelerating these pent-up future cash flows to enhance ongoing R&D and tech-transfer revenue generation would set a new, higher level of ROI from R&D going forward.

Potential Benefits to the US Economy

There is a distinct benefit to uncoupling future R&D innovations from the constraints of US federal program directives and placing it in the hands of the innovative corporations that is significant. While many, if not most, federally directed R&D projects bring benefits to the US economy and everyday citizenry, this constituency now seems to hold a secondary position for many federal agencies’ 2025 primary mission objectives.

If as noted above by the American Institute of Physics assessment of the potential changes to be expected by the new administration, the federal government will be minimizing its support of Basic and Applied research. Becoming self-sufficient and harvesting an enterprise’s legacy R&D-created securitization cash flows could usher in a new and unassailable funding source for future R&D. Is this not the time for the scientific community to direct the course of the future of commercializable technological innovations in America?

In addition to gaining increased control over R&D investment decisions, US companies could increase their liquidity in a very low-cost manner. Because under US GAAP, only the current year’s royalty income is reflected on a company’s balance sheet and income statement. The proceeds from a Carrot Licensing securitization program will increase net income as well as the book value of their balance sheet. It is not unreasonable to expect the licensor’s overall cost of capital to decrease.

Potential Benefits to the EU Economy (EC’s “Technology Sovereignty” Initiative)

The European Commission has for more than a decade been a strong proponent for increased EU-based R&D and its favorable financial and economic impact across several sectors and for companies of all sizes. On its website under the banner “Benefits of intellectual property rights,” the EC states:

“Where a company protects its products or processes with IPRs, [Intellectual Property Rights] it can derive revenues not only from direct marketing but also from licensing the IPRs to third parties that manufacture and commercialise the products, in exchange for a fee or royalty” (emphasis added).

The EU’s promotion of IP licensing targets even includes small and medium-sized enterprises (“SME”) in their programs, one of which is promoted under the banner “Licensing and selling intellectual property.”

The effect of such public policy initiatives in Europe relating to IP is evidenced by the ultimate benchmarking, and score-carding of IP monetization in the marketplace. In 2022, the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) published a “SME Scoreboard” stating:

“SMEs need help to understand the IP landscape and know where they can get finance; easier paths to registration of the most appropriate and accessible rights; help with other tools such as domain names or trade secrets; and assistance to combat infringement.”

Within the 27 countries that in 2024 constituted the European Union, there has been a growing desire to become more self-sufficient in certain areas of high-technology innovations and manufacturing. According to its early definitions, “Technological Sovereignty” is conceived as a nationalist concept, in the sense that its goal is to promote the development of national industries and local capacity for innovation.

According to a paper published in December 2024 by the ECDPM:

“In a global tech sector dominated by the United States and China, the EU faces critical challenges in maintaining its competitiveness, which will likely be aggravated by Donald Trump’s return to the White House. The recent bankruptcy of NorthVolt and struggles of Germany’s AI champion Aleph Alpha highlight the need for a more robust technology ecosystem. Following the Draghi report on EU competitiveness, advocates are calling for meaningful reforms and investments with the aim of driving industrialisation and innovation, and developing sovereign digital infrastructures rooted in democratic values.”

(Chloe Teevan and Raphael Pouyé, Tech Sovereignty and a New EU Foreign Economic Policy, ECDPM.org (Dec. 11, 2024)).

For those R&D-centric companies which participate in the EC’s Technology Sovereignty programs, securitizing their portfolio of Carrot License contract obligations would likely enhance the scope and speed to market of innovations under this EC program. If as a policy of the EC Technology Sovereignty grant programs, it encouraged targeted high-technology company participants in their grant programs to develop Carrot License securitization efforts, then the current year’s funding pressures could conceivably be lowered and allow planned subsidies to be allocated over a longer period of time.

Implications

What CTO has not wished for more R&D funding? What CFO has not wished for more predictable ROI from R&D investments? What enterprise has not wished for a means to augment its limited resources to fuel its competitiveness through innovation? Can these wishes be fulfilled in an environment where government R&D subsidiaries are expected to decrease considerably in the upcoming years?

We believe that the answer is a resounding “Yes” for R&D-centric commercialization enterprises which have been or soon might be proactive in their IP out-licensing activities. Bringing this new “promise-to-pay” asset class to the robust securitization sector comprised of fully vetted and predictable future cash flows is a unique opportunity for such entities to become more self-reliant as government subsidiaries are suspended.

Lastly, while the primary focus of this article has been the Securitization of Carrot Licenses, there exists a similar construct to securitize Stick License contract obligations, which will be the topic of a subsequent article.

This article does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg Industry Group, Inc., the publisher of Bloomberg Law and Bloomberg Tax, or its owners.

Author Information

Dr. Jan Jaferian has been a senior executive for leading high-tech companies and has successfully guided Fortune 50 companies in their global IP protection and monetization strategies throughout the US, European, Asia, and South America. She has enabled companies of all sizes to realize their ROI from their respective R&D commercialization and technology licensing programs.

Christopher J. Leisner, CPA, CMC, of C.J. Leisner LLC has been assisting clients to identify and quantify the value of their intellectual property for over 25 years. He has IP monetization clients that range from sole proprietors to Fortune 50 multi-nationals and is a recognized accounting expert on intangibles, in the classroom, the court room, and the boardroom.

Write for Us: Author Guidelines

Learn more about Bloomberg Tax or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

From research to software to news, find what you need to stay ahead.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.