The arm’s-length standard for transfer pricing valuations isn’t always interchangeable with the fair market value method used for equity valuations. Lisa Banker, Carlos Mallo, Kenneth Christman, and Marina Kashleva of EY explain how the differences can create traps for the unwary taxpayer.

The arm’s-length standard (ALS) (i.e., the standard to be used for transfer pricing purposes) and the fair-market value (FMV) standard of value (i.e., the standard applied for equity valuations and valuations of transactions between unrelated parties) are different standards of value, not “freely interchangeable” as the application of one or the other standard may result in widely different results. Though usually a surprise to the unwary (e.g., many taxpayers), the differences between both standards are apparent in the definition of intangibles, assumptions around synergies, valuation methodologies, and other areas.

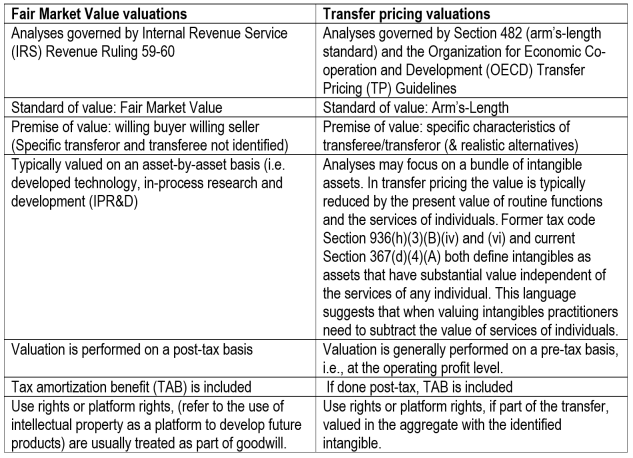

Tax reporting valuations guided by the FMV standard of value and transfer pricing valuations performed under the ALS standard of value often value the same intangible assets and may utilize similar valuation methodologies, for instance an Income Approach, but may produce different results. The table below summarizes the key differences between fair market valuations and transfer pricing valuations:

This article is an attempt to focus on one specific case or manifestation of these differences: the application of the relief-from-royalty method (RfR).

THE COMPARABLE UNCONTROLLED TRANSACTION (CUT)-BASED INCOME METHOD

The cost-sharing regulations under Treasury Regulation 1.482-7 list the RfR as a specified method in the form of the “CUT-based income method”. The CUT-based income method and the standard RfR, commonly used in FMV valuations, are theoretically similar. In practice, however, when valuing intellectual property (IP) that includes use rights, differences in assumptions underlying the two standards tend to produce different results, as explained below. The first difference between the two standards is that while transfer pricing (in the context of cost sharing agreements (CSAs), but more broadly in cases of transfers of use rights where the transferee is responsible for research and development (R&D) expenses) usually subtracts future R&D expenses associated with future developments (since it takes into account the so called “use rights” or “platform rights”), the application of the RfR under the FMV standard excludes use rights from consideration and takes into account the present value of future royalties associated with existing technology only with no subtraction for R&D expenses pertaining to future development efforts. The FMV standard associates R&D expenses relating to new developments with future IP which is not taken into account in determining the value of the identifiable intangible (but may be embedded in the value of goodwill). The second difference is that the transfer pricing CUT-based calculations are done at the operating profit level (pre-tax), whereas the RfR under the FMV is performed on a post-tax basis.

(Note: The CUT-based income method, and the income method more generally, can be used outside the context of CSAs. Outside the context of a CSA, the transferor may be transferring only make-sell rights (i.e., developed technology not subject to further development) and therefore, there is no need to subtract R&D expenses. In the context of a CSA, a platform contribution is a transfer of use rights (i.e., technology to be further developed). In addition, under a CSA, there is a contractual obligation by the transferee to share in future development making the subtraction of future R&D costs to be borne by the transferee a must. It is for this reason that this article focuses on the specific case of CSAs, though a similar analysis would apply to transfers of IP outside the framework of a CSA.)

The basics

Treas. Reg. 1.482-7(g)(iii)(A) describes the CUT-based income method as follows:

“The present value of the PCT [platform contribution transaction] Payor’s licensing alternative may be determined using the comparable uncontrolled transaction method, as described in §1.482-4(c)(1) and (2). In this case, the present value of the PCT Payor’s licensing alternative is the present value of the stream, over what would be the duration of the CSA Activity under the cost sharing alternative, of the reasonably anticipated residuals of the divisional profits or losses that would be achieved under the cost sharing alternative, minus operating cost contributions that would be made under the cost sharing alternative, minus the licensing payments as determined under the comparable uncontrolled transaction method.”

This language requires some interpretation to show the relationship between the CUT-based income method and the RfR.

First, a PCT (i.e., a platform contribution transaction) payment is defined in the transfer pricing regulations as the arm’s-length payment to another controlled participant (in the CSA) that provides a platform contribution (i.e., pre-existing IP) to the CSA. A PCT payment is sometimes referred to as a “buy-in payment.”

Next, it is important to explain that the CUT-based income method may be applied both from the transferor or the transferee perspective.

Let’s first derive the formulas from the transferor perspective. In the cost sharing alternative, the transferor receives (i) the present value (PV) of R&D payments from the transferee (i.e., cost sharing transaction (CST) payments) and (ii) a buy-in payment:

- Transferor CSA alternative: PV(CSTs) + Buy-In

The licensing alternative basically represents the status quo if the transferor does not enter into a CSA. The transferor is assumed to own all IP rights but licenses commercial exploitation rights in the IP (equivalent to those that the transferee would receive in the cost sharing alternative) to a licensee. Thus, the transferor receives the present value of license payments, which equal the present value of sales multiplied by the CUT-based determination of the royalty rate. The royalty rate would reflect the costs to penetrate the foreign market. Ceteris paribus, the higher the penetration costs, the lower the royalty rates:

- Transferor License alternative: PV(license payments) = PV(CUT x sales)

In order to determine the buy-in, the transferor is assumed to act in an economically rational manner. In other words, it will not enter into the transaction unless it is made no worse off. Consequently, the cost sharing and the licensing alternatives must be of equal value, such that the transferor would be indifferent between the two. This assumption leads to the following conclusion:

- CSA alternative = License alternative;

- PV(CSTs) + Buy-In = PV(CUT x sales)

- Buy-In = PV(CUT x sales) - PV(CSTs)Note: For purposes of the analysis, we assume that the discount rate is the same for the cost sharing and licensing alternative. This assumption significantly simplifies the discussion but is only approximately correct. Since the risk borne by the transferor in the two alternatives are not equivalent, the discount rates will not be exactly equivalent. However, we believe in many cases, the difference between discount rates will be small and the distortion minimal

This result is straight-forward: the value of the buy-in (i.e., the arm’s-length value of the IP being contributed to the CSA) equals the present value of the expected royalty payments that a licensor would be entitled to minus the R&D payments that the transferee would be responsible for under the CSA. As a licensor, the transferor can make a certain amount of dollars (i.e. PV(CUT x sales),) but it would have to incur a certain amount of R&D expenses (i.e., the R&D expenses not borne by the transferee).

Let’s now derive the formulas from the transferee perspective:

The cost sharing alternative that the transferee has implies that he/she earns (1) the present value of net-operating profits (NOPs) from developing the cost-shared business in its territory, but it is required to pay the transferor (2) R&D payments (i.e., CST payments) in addition to (3) a buy-in (for transfer pricing purposes Buy-Ins are usually a pre-tax amount):

- Transferee CSA alternative: PV(NOPs) - PV(CSTs) - Buy-In

Under the license alternative, the transferee earns (1) the present value of net-operating profits from developing the business in its territory, but it is required to pay (2) license payments to the transferor:

- Transferee License alternative: PV(NOPs) - PV(license payments) = PV(NOPs) - PV(CUT x sales)

Just as with the transferor calculation, in order to determine the buy-in from the transferee’s perspective, it should be assumed that the CSA and License alternatives are of equal value, such that the transferee would be indifferent between the two.

- CSA alternative = License alternative;

- PV(NOPs) - PV(CSTs) - Buy-In = PV(NOPs) - PV(cut x sales); and therefore, the Buy-In should equal

- Buy-In = PV(CUT x sales) - PV(CSTs)

In both instances (under the transferor and the transferee perspective) the formula for the buy-in leads to the same result: the buy-in equals the present value of the stream of future expected royalties less the present value of the R&D expenses the transferor is no longer required to pay as a result of the other CSA participant’s obligation to cover these expense. In other words, if the transferor is to be made whole under both alternatives, it would transfer the IP for one or more PCT payments that equal the forgone license payments on an expected present value basis. However, under the licensing alternative, the transferor must commit to R&D expenses in order to extend the life of the IP that is being licensed. An interesting point relates to the value of the R&D activities as these activities clearly qualify for development, enhancement, maintenance, protection, and exploitation (DEMPE) functions under the OECD guidelines. The value of these DEMPE functions, under the current CSA regulations are part of the buy-in value. Because in the cost sharing alternative the transferor is relieved of a portion of these expenses, the transferor will accept PCT payments reduced by the expected present value of the R&D expenses it is relieved of.

As discussed below, FMV applications of the RfR estimate the value from the present value of foregone royalties and do not usually subtract R&D expenses.(in fact, FMV values a different cash flow because the cost of future technologies and the value of use rights are typically considered as an element of goodwill). Furthermore, the RfR under the FMV is a post-tax number, whereas for transfer pricing purposes, the calculations are done at the operating profit level (pre-tax basis). The transferor must be made no worse off on a post-tax basis if it is to enter the transaction. However, the PCT value is a pre-tax number as the IRS does not want to collect taxes over an amount already reduced for taxes. See Treas. Reg. 1.482-7(g)(2)(x). Mechanically, the subtraction of R&D expenses (ceteris paribus) would reduce the value of the IP, but the fact that the valuation is calculated pre-tax arguably results in a higher value of the IP. The impact of tax on IP valuation is beyond the scope of this article. Rather than delve into this difficult topic, we merely note that the transferor has to receive a sufficient amount to be made no worse off by transferring the IP and the transferor is potentially subject to tax on any buy-in payments it may receive. Consequently, paying the transferor the expected present value of the after-tax income the transferor is giving up by transferring the IP will not be sufficient to induce the transferor to transfer the IP.

In-depth analysis: the scope of the valuation under transfer pricing

In transfer pricing, we distinguish between make-sell rights and use rights (also called platform rights). Make-sell rights are the rights associated with the commercialization of a developed technology/product. Alternatively, use rights refer to the use of intellectual property as a platform to develop future products. From a technical perspective, if the RfR were applied to a transfer of make-sell rights, there would be no need to subtract R&D expenses because there are no associated future development expenses, as the product is already fully developed. However, the transfer of certain IP usually includes the right to further develop that IP. This implies two things: first, that the life of the IP is significantly longer, and second, that the transferee must continue to engage in R&D activities in order to continue the development of the IP over time.

As a result, the application of the CUT-based income method implicitly aggregates the make-sell and the use rights, which is why the R&D expenses are subtracted. As further explained in the analysis of the RfR under the FMV perspective below, make-sell rights (developed technology), in-process technology (make-sell rights that require some additional R&D) and future products (for FMV under goodwill) will all be valued separately. These separate valuations would then lead to different RfR results: for example, the life used under the FMV for the application of the RfR for developed technology (pure make-sell rights) would differ from the life used for the calculation of a CUT-based income method that aggregates make-sell and use rights.

Finally, it is important to note that under both the now repealed Section 936(h)(3)(B) and the new Section 367(d)(4)(A) which replaced it, the definition of intangible excludes any item of value or of potential value that is attributable to tangible property or the services of any individual. The language poses an interesting conundrum to the transfer pricing valuations of use rights (future IP), as they are inseparable from R&D activities (DEMPE activities) and invites the question of whether there is any value beyond the DEMPE functions—the answer to which is probably “yes”. The intangible asset has value because it is a platform. In other words, it creates the possibility of a return higher to R&D functions that one might expect in a green field.

RfR UNDER THE FMV

ForWhere do they want the graphic? We can’t do wrap-around text, so I need to put it between paragraphs.

Should go after the definition of FMV

US tax reporting purposes, the standard of value is FMV. According to IRS Revenue Ruling 59-60 FMV is defined as:

“… …the price at which the property would change hands between a willing buyer and a willing seller when the former is not under any compulsion to buy and the latter is not under any compulsion to sell, both parties having reasonable knowledge of relevant facts.”

The method is typically used to value technology or trade names in support of Section 1060 analyses (i.e., purchase price allocation for tax reporting purposes).

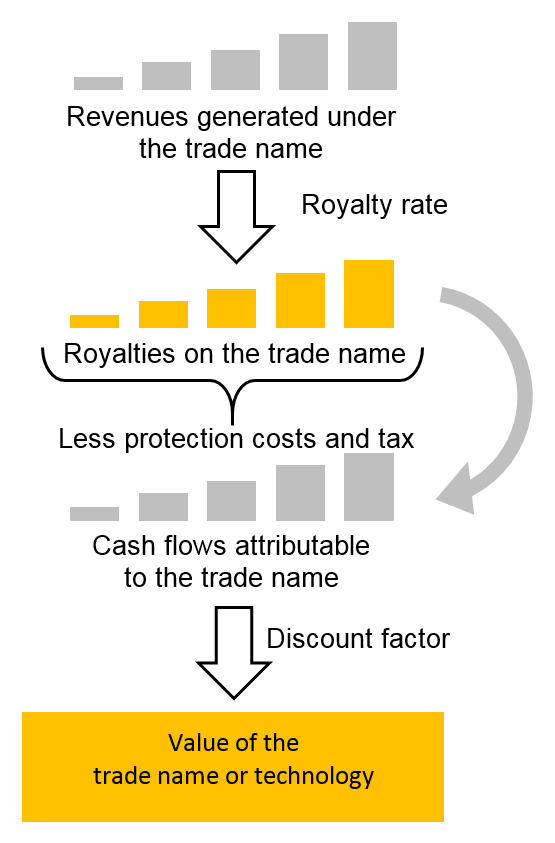

The basic tenet of the RFR Method is that without ownership of the subject intangible asset, the user of that intangible asset would have to make a stream of payments to the owner of the asset in return for the rights to use that asset. By acquiring the intangible asset, the user avoids these payments.

Another key difference, as noted above, is that under FMV, the IP is valued ‘as is’ on the Valuation Date without consideration to future enhancements unless they reflect evolutionary upgrades. For instance, developed technology will be valued typically up-to the expiration of the patent and not beyond unless there are certain economic benefits expected beyond patent expiration (that may include a small tail post patent expiration). Further significant enhancements will require additional research and development efforts so they will not be considered in the asset that is being valued today. The use rights that may be considered in transfer pricing are considered to be a component of goodwill under FMV.

Within the RFR Method, expected cash flows can be directly assigned to the asset and discounted with an appropriate discount rate.

In using this method, royalty or license agreements between unrelated parties are analyzed. The royalty rate selection process should consider the third-party data as well as profitability of the associated revenue stream. The licensing transactions selected should reflect similar risks and characteristics that make them comparable to the subject asset. The net revenue expected to be generated by the intangible asset during its expected remaining life is then multiplied by the selected benchmark royalty rate. The estimated royalty stream after tax is then discounted to present value, which results in an indication of the value of owning the intangible asset.

Application of RfR method

The valuation methodology selected for the valuation of the intangible asset should most accurately capture the benefits of owning the subject intangible asset given the nature of the asset and the availability of information required for the analysis.

In cases when the subject asset represents a key asset of the business and there is an identifiable stream of prospective cash flows available, the multi-period excess earnings method rather than the RfR method is applied to assess the FMV of the subject asset.

In cases other significant assets are held by the business, the RfR method may be applied to assess the FMV of the subject asset.

Generally, the RfR method is applied in the situations where:

- The importance of the intangible asset to a business or product is similar to that of a comparable licensed asset (for example, consumer assets);

- The intangible asset can be reasonably separated from other assets and it is practical and possible to license it separately;

- The rights of ownership can be compared to the rights under a license (for example, similar geographic market coverage, duration, exclusivity, limitation, technology and type of customer);

- Royalty rates can be observed, including rates for agreements that confirm comparable economic rights for similar intellectual property.

FINAL REMARKS AND CONCLUSION

It is important to understand that the standard of value (FMV vs. transfer pricing) considered in a specific analysis is driven by the underlying code section governing the purpose of the analysis. The filers should consult with their legal counsel, internal tax teams and/or external tax advisors to ensure the appropriate standard is used. Though it is common that both valuation and transfer pricing professionals value assets using the RfR method, it is likely that the result of those valuations will differ. As discussed above, one important reason for this gap has to do with the allocation of value to goodwill (for FMV purposes) or to platform / use rights (for transfer pricing purposes). In other words, it is important to understand the difference between the asset being valued in each case, as this will have an impact on the cash flows considered in the analysis. For example, if a perpetual license associated with the IP is being transferred, existing and future IP-related cash flows would be included, but if existing IP is being transferred, only cash flows attributable to existing IP would be captured. Note, however, that if someone would value make-sell rights alone, it is likely that RfR and CUT-based income methods would result in very similar though probably not identical values (due to other differences between the two standards such as the treatment of tax).

Note that under a transfer pricing valuation that combines make-sell and use rights, the whole value is attributed to identified intangibles, significantly reducing the value attributable to “goodwill”. This issue has an enormous impact both for book and tax purposes (e.g., it affects amortization benefits). In addition, this issue is not specific to the U.S.; it arises in many jurisdictions around the world.

As a result, valuation and transfer pricing professionals should pay careful attention to these differences between the valuation standards and coordinate among themselves in order to better serve their clients. In addition to the critical goodwill/use rights issue, there are three other significant sources of differences, that are no less critical. First, there is the valuation perspective issue explained above (i.e., willing buyer-willing seller versus the specific characteristics of transferee-transferor), which can make a difference and should always be kept in mind by the valuation professionals. Second, there is the pre-tax versus post-tax issue. The consideration of a “tax shield” provided to the transferee by purchasing the IP, typically, provides a good compromise between the two standards. Note, however, the fact that in FMV you do not necessarily look at the specific tax attributes of the transferee (which in theory TP should under the ALS) but rather at the attributes of a willing buyer, and this may still create a different result.

Another possible way to accommodate the differences in standards is the use of ranges. For example, the transfer pricing professional can create an IQR of pre-tax values that includes the post-tax value from the FMV. Third, there is the more practical issue of how to determine the royalty rate (and whether the royalty rate includes the right to develop new IP, i.e., use rights, or not). Transfer pricing studies tend to look at a wider set of comparable agreements than FMV valuations, and it is not uncommon that transfer pricing professionals perform different types of comparability adjustments (e.g., adjustments related to exclusivity or not, etc.).

As a result of the above, it is imperative that clients, valuation and transfer pricing professionals coordinate valuations. It is important to keep in mind that though a transfer pricing valuation may not be required at a certain moment, it may be required down the road, and consistency between the FMV and transfer pricing valuation could have significant tax impacts for clients at a later date. For example, assume that a company acquires a target company (assume it is a stock acquisition followed by a Section 338 election). An FMV valuation would be made at the point of the acquisition determining basis in the identified intangibles (class VI intangibles) and goodwill (class VII intangibles). A few years later, the company may transfer some of the identified intangibles to a foreign related party. At this time, the value of the IP will be determined in a valuation consistent with the arm’s-length standard, however, the basis was determined at the time of the acquisition under a FMV valuation per the underlying tax code section governing the analysis. As the previous example shows, differences between the FMV and the arm’s-length standard may create dangerous traps for the unwary.

Valuation similarities

The valuation methodologies under FM Valuations and transfer pricing (TP) frameworks are similar in concept and approach, particularly the income-based methods. Each methodology (FMV and ALS) entails preparing a discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis based on forecasted financial performance. A DCF analysis requires determining appropriate estimates of useful life of the intangible asset and the applicable discount rate. [Under the CSA regulations the IRS allows the use of different discount rates for the calculation of the present value of the cost sharing and the licensing alternative. In addition, practitioners have discussed at length the use of pre or post tax discount rates.]

The CUT-based Income Method and RFR Method both involve identifying uncontrolled license agreements to determine appropriate returns attributable to intangibles.

Key differences

There are certain key differences in the valuation approaches for FMV and TP purposes. As a result, there can be a substantial value gap between valuations under these two standards. This paper has discussed some of these differences but there are others, not covered by this paper, such as accounting for routine returns, bundling of IP and use of terminal values. Though not discussed in this paper, for sake of completeness we briefly mention these other differences as part of our final comments.

- Perspective for determining best method for valuation. FMV analyses operate under a “willing buyer/willing seller” perspective, while TP valuation relies on specific characteristics of the transferee or transferor and “realistic alternatives” concept.

- Accounting for Routine Returns. TP valuations subtract routine returns (e.g., for manufacturing, distribution activities) to arrive at residual profit (routine returns are usually calculated based on the returns earned by comparable companies). FMV analysis under the excess earnings method apply contributory asset charges to account for the utilization of fixed assets, net working capital and other supporting intangible assets. (This difference applies in the case of the CPM-based Income method or DCF/MPEEM but does not affect RfR).

- Bundling vs. Identifiable Assets. Many TP valuations analyze an entire intangible asset portfolio, rather than a specific IP asset class. The reason for that is that TP valuations focus on the value transferred, rather than identifying specific assets. The bundling approach has become more prevalent after tax reform in the US. The FMV analyses typically value specific assets as described in Section 1060. Goodwill is considered a residual asset and is not specifically valued

- Use of Terminal Values. It is rare for a valuation under the FMV standard to use a terminal value as the typical asset/IP under consideration focuses on economic benefits generated by the subject asset/IP over a period of time until the current base of the asset/IP becomes obsolete assuming cessation of any R&D activities related to enhancements. As noted above, only assets that can be recognized separately from goodwill as of the valuation date are valued (including IPR&D). Any intangible asset value that is not separately valued is captured in a residual asset known as goodwill. Under the FMV standard, goodwill represents the buyer’s ability to develop new technology, enter new markets, have a going concern company and have a fully trained assembled workforce etc. For TP purposes, what FMV professionals assign to goodwill, is considered to represent the value of the platform, that is “use rights” (again, subject to the exclusion of the services by individuals performing R&D activities).

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of The Bureau of National Affairs, Inc. or its owners.

Author Information

Lisa Banker is a partner in Transaction Advisory Services, Valuation, Modelling & Economics at Ernst & Young; and Carlos Mallo and Kenneth Christman are managing directors and Marina Kashleva is a senior manager in International Tax & Transaction Services (Transfer Pricing).

The views expressed are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of Ernst & Young LLP or other members of the global EY organization.

Learn more about Bloomberg Tax or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

From research to software to news, find what you need to stay ahead.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.