Should the Covid-19 virus, declared by WHO on March 11 as a pandemic, be used to invoke force majeure and amend transfer pricing policies? Glenn DeSouza addresses this question with cases and solutions based on the latest Chinese legal, accounting, and economic developments.

The American economist Nouriel Roubini, who famously early-called the 2008 meltdown, is warning that “This trifecta of risks—uncontained pandemics, insufficient economic-policy arsenals, and geopolitical white swans—will be enough to tip the global economy into persistent depression.”

Not so in China. Here the virus seems to be just a hiccup on a continued growth trajectory. China is beating the virus on the economic front. And without any monster bailout package. There are no checks in the mail. No funding of airlines or troubled industries. There is not even an extension to the tax filing deadline of May 31. But the economy appears to be gearing up for a rapid come back.

JP Morgan Research, the research arm of the investment bank, is predicting that the Chinese economy will grow by 15% quarter-on-quarter from April to June after contracting by 3.9% in the first three months of this year, compared with the final quarter of 2019. By contrast, JP Morgan slashed forecast for U.S. GDP sees 14% second-quarter drop. The U.S. economy could shrink 4% this quarter and 14% next quarter, and for the year is likely to shrink 1.5%

For the full year, it is expected that the impact on China may be modest. The International Monetary Fund said it was cutting its growth outlook for China’s economy by 0.4% to 5.6%. “In our current baseline scenario, announced policies are implemented and China’s economy would return to normal in the second quarter. As a result, the impact on the world economy would be relatively minor and short-lived,” IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva said in a statement.

How Will Tax Bureau Treat Multinationals

Some advisers have been sounding Jeremiads that the virus will lead to a crackdown by tax bureaus. To summarize they feel that “Governments and tax authorities will place greater emphasis on transfer pricing, in order to fill the hole in national budgets caused by the anticipated economic slowdown and will focus on multinationals”

Our position based on discussions with the tax bureau is that this need not be the case. Senior tax officials are members of the CPC and see themselves as patriots who must advance national goals. And right now the national priority is jobs and investment and not tax collection. Premier Li Keqiang has stated that “Keeping employment stable is our top priority this year. Related departments must work in synergy to support”

Thus tax officials are going easy on job-creating multinationals. Our discussions with tax officials in some areas fact indicates that they have not launched any new audits this year. One reason they mentioned is their inability to conduct field work due to the quarantine. They also stated that they are not facing pressure from above to meet tax collection goals. They plan to start on audits in second half of the year but to avoid targeting any major job producers and to instead focus on sectors such as luxury goods and services.

Transfer Pricing Options for Cost-Plus Subsidiaries

In the typical global transfer pricing model used by multinationals, the Chinese subsidiary is compensated using a cost plus model and any extra profit is swept back Stateside or to an intermediate low-tax jurisdiction. Normally, this structure, set up in fact to minimize the global effective tax rate (GETR), is very tax-advantageous but not of course this year.

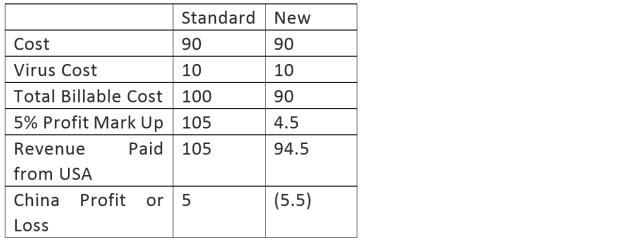

A question raised by clients is whether the costs associated with the virus should be included in the cost base and compensated by the U.S. parent. The answer is that multinationals may be able to take the position that the costs of the virus should be borne by the local affiliate. This action can reduce or even eliminate their China tax bill as illustrated by the example below:

Transfer Pricing Options for Entrepreneurial Entities

There are also many multinationals who place their China entity on an entrepreneurial basis especially, in such sectors as retail or luxury, if the local company is selling to the domestic market. In this model, the China entity captures the profit but pays the overseas parent a royalty and possibly also a service fee. Now with COVID-19, the China entity could be in a loss and so there is an issue of whether to waive the royalty or accrue it. Note that continuing to pay the royalty could create a cash flow problem requiring a group interest-free loan or external funding.

Yet another consideration is whether to help the China entity by lowering the price of products it imports from the parent or by making a transfer pricing adjustment to cost of goods sold. This is a complicated matter because there are customs duty and VAT implications that are difficult to resolve.

Debate on Quantifying Virus Cost

In deciding on how to change transfer pricing, the first step is to quantify the cost impact of the virus. Our discussions with auditors and clients indicates this is a matter of considerable debate.

Firstly, with regard to “direct costs” these are readily acceptable as virus related and auditors have incorporated such costs into their U.S. GAAP statements. These acceptable direct costs are listed next.

- Labor costs related to paying employees who did not work due to the extended Chinese New Year holiday and quarantines imposed on them due to traveling from infected areas.

- Medical control and supervision costs such as face masks, hand sanitizers, thermometers, personal protection equipment, and also cost of renovations to the factory and canteen to meet medical certification requirements of the government.

The indirect costs—a matter of debate—are listed next:

- Fixed costs such as rent and depreciation on a unit basis which soared because during February factories were only at 20% to 30% capacity.

- Supply chain disruption costs including loss of production due to material unavailability, additional logistical costs and write-down of inventory

- Decline in demand, especially for fast foods and retail and consumer goods where stores were closed. For example, in China, auto sales plunged 82% in February 2020 compared to the sales in the same period last year.

Will Future Demand Surge Offset Cost?

The luxury goods industry took a massive hit, not surprising given that Chinese citizens account for over 40% of worldwide demand. For example, Burberry has closed 24 of its 64 stores in mainland China since the virus erupted. A study by Boston Consulting Group (BCG) said sales plunge to levels not seen since 2015 and wipe out €10 billion ($11 billion) in luxury brands’ profits this year. But what happens if instead the customers who did not buy that handbag in January makes up that purchase in June? In other words, for some industries, there may be a surge in demand that could offset in part the losses incurred in the first quarter. Thus, we recommend a system to track the COVID-19 related costs on a regular basis.

Invoking Force Majeure

The World Health Organization declared COVID-19 to be a pandemic on March 11, 2020. The COVID-19 Virus may qualify as a force majeure event, which gives the multinational the legal basis to change its transfer pricing. The “Contract Law of the People’s Republic of China” has the following provisions in this regard:

- Article 117: Where a contract is not able to be performed due to force majeure, the liabilities shall be exempted;

- Article 118: Either party to a contract that is not able to perform the contract due to force majeure shall give a notice to the other party in time.

- Article 94.1: The parties to a contract may rescind the contract due to force majeure

Multinationals need to check their intercompany agreements with the China subsidiary. The ideal force majeure clause would: (1) specifically cite epidemics, and (2) grant the parties the right to terminate or amend the agreement. This is illustrated by the sample below:

“A party will not be liable to the other party for any failure, delay, or disruption of services, caused by a Force Majeure Event. ’Force Majeure Event‘ means any cause beyond the reasonable control of a party that could not, by reasonable diligence, be avoided, including acts of God, acts of war, acts of civil or military authorities, denial of delays in processing of export license applications, earthquakes, epidemics, embargoes, fire, floods, riots, terrorism, accidents or strikes. If the delays caused by force majeure conditions are not cured within thirty (30) days of the force majeure event, then either party may immediately terminate this agreement.

Whether an event qualifies as a force majeure depends on the circumstances. During the SARS epidemic the Chinese courts ruled in some cases that it did.

To be eligible for force majeure protection under PRC law, the affected party must demonstrate that the relevant situation is unforeseeable, unavoidable and cannot be overcome, and also that it is the cause of the affected party’s inability to perform its obligations.

The China Council for The Promotion of International Trade has been issuing force majeure certificates to companies that claim they are unable to meet their contractual obligations to protect them from potential breach of contract claims by counterparties.

Contemporaneous Comparables as Support

Comparables are the work horse of transfer pricing and the orthopraxy is to apply a 3-year average (which would be 2016-2018). But this practice would not cover the period of the COVID-19 impact. Thus, in preparing additional support as to why the Chinese subsidiary should have a reduced profit or loss, the best recourse would be to look at the 2020 first quarter results. Our study across a wide range of companies who have released first quarter results finds a sharp decline in revenues and other financial indicators compared to the same period last year.

Action Plan

How to deal with the COVID-19 virus when it comes to transfer pricing is a question to which there is no single right answer. It depends on the industry and the type of transfer pricing arrangement. But there are some general best practices as laid out below:

1. Determine whether to stay with the current policy or change the policy to deal with the virus;

2. If the policy is to be changed, invoke force majeure to amend the intercompany contract to reflect the new transfer pricing policy;

3. Quantify the cost impact of the virus and conduct other analyses such as on “quarter 2020 comparables” or value chain to support the change in policy;

4. Possibly conduct no-name discussions with tax bureau to minimize subsequent risk; and

5. Set up a tracking system to monitor virus costs during the four quarters and do an end-of-year transfer pricing adjustment if needed.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of The Bureau of National Affairs, Inc. or its owners.

Author Information

Glenn DeSouza is a national transfer pricing leader at Dentons China based in the firm’s Shanghai office. Glenn may be reached at Glenn.Desouza@dentons.cn.

Learn more about Bloomberg Tax or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

From research to software to news, find what you need to stay ahead.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.